When US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III lands in Kyiv he will find Ukrainian officials which are eager to talk on issues he oversees in the US government. For Ukraine, which has been subjected to continuous Russian aggression since 2014, the issue of military security is of paramount importance with its survival at stake.

Alas, it’s not an exaggeration. As NATO and Russia trade accusations of massing troops and creating new permanent military infrastructure along each other’s borders, it's precisely along Ukrainian frontiers where Russia has been engaged in the most active military build-up in the last 7.5 years.

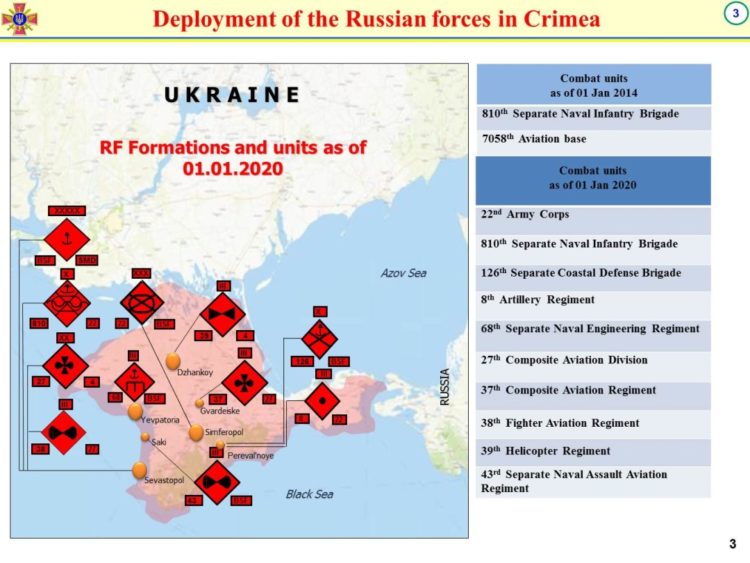

In both Western and Southern Military Districts of Russia, the majority of new permanent military infrastructure was created along mutual border with Ukraine – 20th Combined Arms Army (CAA) in the northeast (Bryansk, Kursk and Voronezh regions), 8th Combined Arms Army in the east (Rostov and Volgograd regions) and 22nd

Army Corps in the south (occupied Crimea).

According to estimates provided by the chief of Ukrainian Land Forces, these new Russian formations near the Ukrainian border can generate approximately 31 battalion tactical groups (BTGs) – or more than 20 percent of all Russian BTGs which numbers 146 according to some authoritative estimates.

But for Russia, it’s not enough.

Back in April 2021, Moscow made clear that it can quickly and easily reinforce those forces along Ukrainian frontiers with additional CAAs and formations of Air-Borne Forces in case of need. So-called strategic mobility – the ability to quickly create and reinforce interservice grouping of forces at any strategic direction – was again tested by Russian Armed Forces in this year Strategic Command and Staff Exercises ZAPAD-2021 conducted in Western Military District of Russia and Belarus.

This was admitted back in March 2015 by the head of US Army in Europe lieutenant-general Ben Hodges. Russia's obsession with Ukraine is not only an issue of major concern for Kyiv but, in a certain respect, Ukraine’s immense contribution to the common Euroatlantic security.

This grave situation was only exacerbated by the July 2021 controversial joint US-German statement greenlighting the completion of the dubious North Stream II pipeline.

North Stream II, working in full capacity along with Turkish Stream, would render the Ukrainian gas transit system redundant and deprive Ukraine of 2 billion dollars of transit fees. But more importantly, it would obliterate Russia's dependence on Ukraine for gas transit and give the Kremlin less reason for restraint, as it would remove the need to consider the stability of gas flows via Ukraine.

Given this situation on the ground, the idea of stable and predictable relations with Russia first broached by the White House in mid-April 2021 (amid a major Russian military build-up near Ukraine) is unpersuasive if you look at it from the Ukrainian perspective.

Yes, Ukraine is also interested in stabilizing the ongoing US-Russian confrontation, as it’s one of the first countries to feel negative repercussions if this confrontation comes out of control. But real stabilization would be out of reach if this huge disparity of power potentials between Ukraine and Russia is preserved: Moscow might at any time create another crisis on Ukrainian borders, threatening its neighbor with all-out war, with all ensuing negative consequences for Euroatlantic security.

The only logical decision in this context is to increase the amount of US security assistance to Ukraine, directing it to the most promising items based on calculations of investments and outcomes.

It's correct that in the last 7.5 years Ukraine received approximately $2.5 billion of US security assistance – with an additional $60 million being promised by the US government when Volodymyr Zelensky visited Washington last month. But to say this is enough would be a misstatement.

Ukraine spends on defense annually approximately $4 billion (1UAH 117 billion) or 2.6% of its GDP. Russia spends approximately $42-43 billion annually on defense – so even in absolute terms, there is a huge gap which might be even bigger if we look at the situation through the lens of purchasing power parity. That’s why if we imagine the situation that each hryvnia of the Ukrainian defense budget is spent in the most efficient way (which is still more goal than reality, to be honest) the existing gap between Russia and Ukraine in the military field would still be huge.

Therefore, foreign security assistance is of utmost importance for Ukraine as incumbent National Security Strategy attests – with the US as the most important partner.

What is also true that any assistance needs to be reassessed from time to time to be the most efficient and impactful. That’s why section 1236 of NDAA for FY 2021 clearly required US DoD to submit "a report on the capability and capacity requirements of the military forces of the Government of Ukraine." This idea is a step in the right direction, as only a thorough analysis might indicate the best avenues for the investment of always limited resources.

But even without in-depth research, it’s clear that Ukraine still needs such defensive items as anti-tank guided missiles, MANPADs, secure command and control devices, armored all-terrain vehicles to name just a few items – for the Ukrainian Armed Forces to be able to make Russia pay a solid price in case of all-out aggression.

The issue of increase in US security assistance to Ukraine can be seen from another perspective – namely current inability to reconcile differences surrounding Ukraine's bid to join NATO.

On the one hand, there is Ukraine's rightful claim to join this most efficient security provider on the European continent – remembering the fact that Ukrainian attempts to take into consideration Russian interests by observing a non-aligned status in 2010-14 failed spectacularly.

On the other hand, there is a mismatch between NATO members’ rhetoric and action. Formally, NATO member states still adhere to the April 2008 Bucharest Summit communique, which made clear that Ukraine one day will be a NATO member – that’s the main idea of paragraph 69 of the June 2021 Brussels Summit communique. But now there are not only the traditional skeptics like Germany and France when Ukrainian membership in Alliance is at stake. US government statements made clear that today official Washington is much more cautious than during Ukraine's previous NATO bid in 2008.

No NATO plan for Ukraine. What Zelenskyy and Biden promised — and did not promise — each other

There are different reasons why this is so – problems with internal reforms in Ukraine, Russia's increased capacity to wage a high-intensity war on its periphery after 12 years of reform and modernization of its Armed Forces.

But US restraint with regards to Ukraine's desire to join NATO right now is an undisputable fact.

Under these conditions, an increased shipment of defensive armaments by the US to Ukraine might be a good substitute for its inability to bring Ukraine to NATO right now, with NATO membership for Ukraine preserved as a long-term goal.

There are some positive signs that some increase in US security assistance is on the horizon. Congress debating NDAA for FY 2022 is ready to approve $300 million in security assistance to Ukraine via US DoD compared with $275 million provided via US DoD during FY 2021. But still, this level of ambition on Washington's Capitol Hill is smaller than the recommendations of many authoritative US think tanks and experts. Plus remember that for Ukraine, which spends approximately $1 billion on armaments annually, a couple of additional hundred million dollars on defensive weaponry would make a huge difference allowing to buy necessary additional defensive items.

Naturally, the Russian response would be furious – Kremlin would try to portray the shipment of additional defensive armament and increase in US security assistance to Ukraine as destabilization and an escalatory step.

Of course, this is far from the truth. Security assistance for Ukraine are only an attempt to decrease the abovementioned huge disparity of power favoring Russia through the pointed application of funds to Ukraine's defense. US and Ukraine along with other international partners can credibly make the right case before the international community why such actions are necessary.

Truly stable and predictable relations with Russia are possible only when the whole eastern flank of NATO is secure with the right balance of power – including at the Russia-Ukrainian border.

Related:

- No NATO plan for Ukraine. What Zelenskyy and Biden promised — and did not promise — each other

- Why Ukraine does not (yet) “deserve” NATO membership

- Is Ukraine getting closer to NATO membership?

- The 2021 Brussels NATO summit: triumph or defeat for Ukraine?

- Kyiv airing disappointment with Western policies

- Javelins, reform plan, and $2.5 bn of military aid: Ukraine and USA sign joint statement on strategic partnership

- Here is how the US can truly help Ukraine move forward

- Long term military mentorship to Ukraine, founded in trust: the California-Ukraine State Partnership Program