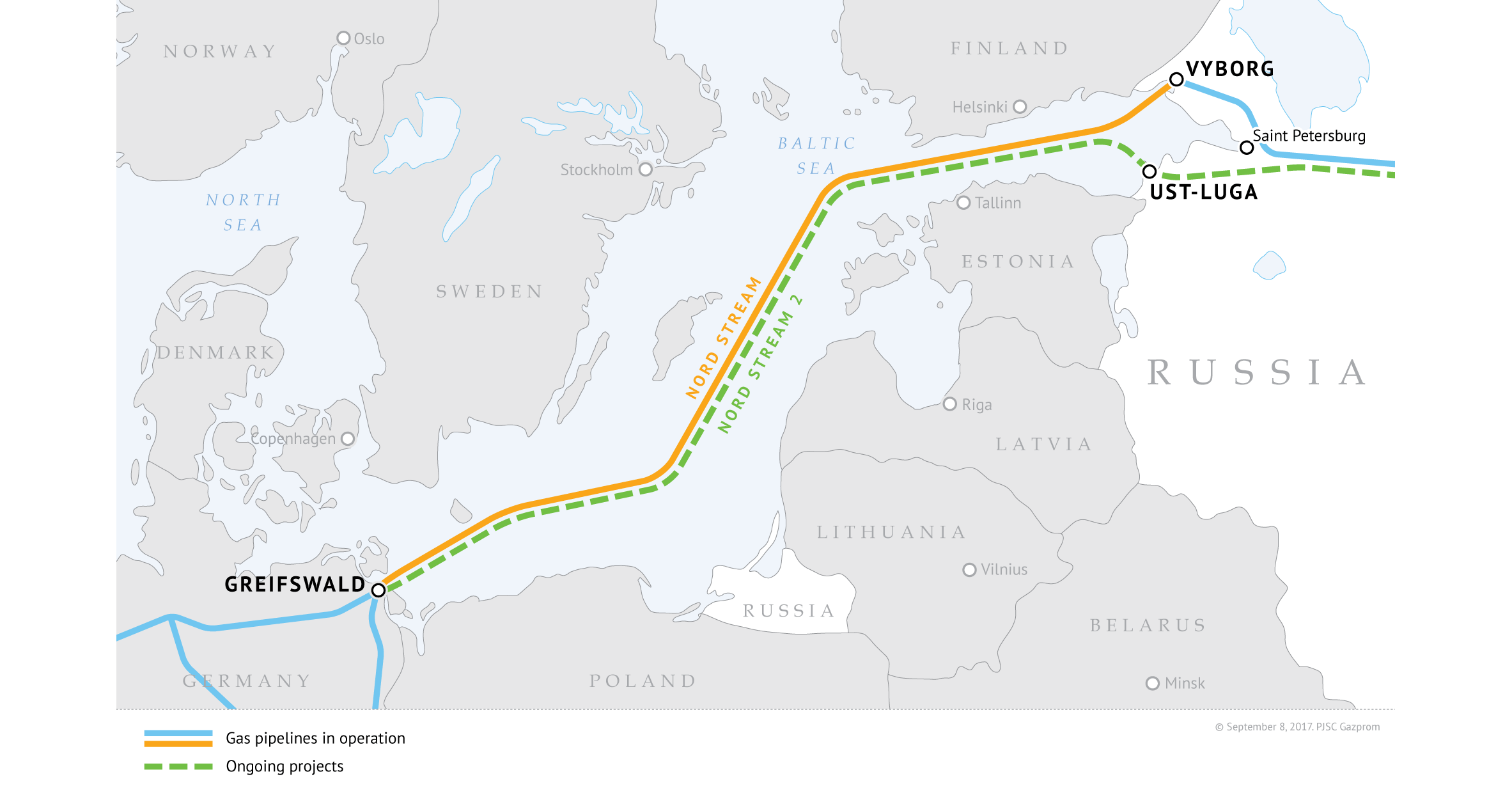

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline consists of two parallel strings, each with a capacity of 27.5 billion cubic meters (bcm), totaling 55 bcm annually. The existing Nord Stream 1 pipeline has the same capacity, allowing for 110 bcm of Russian natural gas to be delivered directly to Germany, or over 65 percent of all Gazprom exports to the European Union. Currently, Germany buys 57 bcm of Russian gas, delivered through Nord Stream 2 and Yamal Europe through Poland (Gazprom, 2019). Open season bookings for pipeline capacity show that Germany will only retain about 10 bcm of the gas supplied through Nord Stream 2; the rest will be transferred to Central Europe from the western direction, making redundant Ukraine’s gas transmission network.

If completed, Nord Stream 2 will divert to Germany most of the Russian natural gas currently transmitted to Europe via Ukraine—55.8 bcm in 2020 (Naftogaz, April 28).

Another new Russian pipeline under the Black Sea, TurkStream, became operational in January 2020 and has already diverted approximately 20 bcm of natural gas previously transported via Ukraine through the Trans-Balkan pipeline. That line became redundant and is facing decommissioning (See EDM, January 16, 2020).

Ukraine stands to lose almost all Russian gas transit and its status as a major international natural gas corridor, critical for Europe and Russia. The security implications stemming from such a prospect are far more significant than the loss of $2.5 billion in gas transit fees annually. Ukraine’s gas pipeline network is considered “a key element of the country’s defense system,” so long as it remains a key to Russia’s European gas exports, says Andriy Kobolyev, the former chairman of Ukraine’s gas company Naftogaz (Upstream, February 18).

Speaking at the St. Petersburg economic forum, the Russian president blamed Ukraine for the pending loss of Russian gas transit. “Ukraine destroyed everything with its own hands,” he claimed (Vesti.ru, June 4). In fact, the Kremlin’s decision to construct two new mega pipelines in the Baltic and Black seas has broad strategic objectives. It aimed to bypass Ukraine as a gas transit country, encircle Central and Eastern Europe in a pincer movement to dominate its gas market, suffocate regional market development and restrict alternative gas suppliers. Dividing EU members, most of whom oppose Nord Stream 2, and challenging EU energy and competition regulations is also part of these objectives.

But Putin sounded more conciliatory when discussing the future of Russian gas transmission through Ukraine, noting Gazprom’s current five-year contract with Naftogaz and leaving the opportunity open for new agreements. Clearly, Moscow wants to keep the door open for continuing usage of the Ukrainian route if the pipeline’s certification is delayed or contested. Putin recognized that the pipeline is entering the sphere of EU laws on gas pipelines, saying, “Gazprom is ready for deliveries, but everything will depend on the German regulator” (EUobserver, June 7).

Two provisions of the Gas Directive, Article 11 and the amended Article 36, are of particular concern to Gazprom, the pipeline’s single owner. The amendments to the Gas Directive adopted in 2019 subject gas transmission pipelines to and from third countries to the rules for internal pipelines. The obligations for unbundling, third-party access and transparent tariff regulation apply to all lines from non-EU states.

Obtaining an exemption from Article 36 will be a difficult task. As a diversionary pipeline that does not bring new gas to Europe, the Nord Stream 2 owner will have a hard time convincing the German regulator and the EU Commission, which reviews these decisions, that an exemption will not be detrimental to market competition and internal market development and the security of natural gas supplies (Gas Directive, April 17, 2019).

Trapped in legal hurdles and faced with the prospect of lengthy litigation brought by some EU members, Gazprom may have little choice but to agree to continue using the Ukrainian route to export specific gas volumes. The levels could be potentially equal to those in the current contract between Russia and Ukraine for about 40 bcm annually. Although such an agreement would require a reliable enforcement mechanism, it could offer a solution that meets both imperatives—to preserve some of Ukraine’s revenue from gas transit fees and, much more importantly, to keep Ukraine’s significance to Russia and the EU as a gas transit country. The latter is paramount for protecting Ukraine’s security.

A newly laid pipe reads, "Pipe to your sanctions, Mr. Reagan" (the "pipe for something" is a Russian idiom meaning "failed, done, kaputt"). Construction works of the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod pipeline. USSR, 1982. Photo: Public Domain

A newly laid pipe reads, "Pipe to your sanctions, Mr. Reagan" (the "pipe for something" is a Russian idiom meaning "failed, done, kaputt"). Construction works of the Urengoy–Pomary–Uzhhorod pipeline. USSR, 1982. Photo: Public Domain

At the peak of Cold War tensions, the Reagan administration was afraid that a new high capacity gas pipeline will give the USSR an energy leverage over Western Europe as well as well as the gas export revenue could be used for the military purposes. In 1981-1982, the US imposed sanctions preventing US companies and their subsidiaries in Europe to export oil and gas technologies to the USSR. Europe allies refused to boycott the pipeline then.

History repeats itself with the Nord Stream 2, which was recently green-lighted by Germany.

Much stronger protection and deterrence of further Russian aggression against Ukraine could be offered by Germany, if indeed, Chancellor Angela Merkel succeeds in convincing German companies to make significant investments in Ukraine’s green energy sector. As reported by Handelsblatt, to complete the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project without further US sanctions, Berlin has offered Washington greater economic support for Ukraine (Handelsblatt, March 18). Germany has been particularly interested in supporting hydrogen gas production in Ukraine. Leaked documents spell out German intentions to invest in this sector, calculating that Ukraine can produce one-sixth of the hydrogen gas needed for Europe’s green transition—7.5 gigawatts out of 40 gigawatts planned for generating in the EU by 2030.

Further reading:

- Time to stop Nord Stream 2 now: open letter by Ukrainian politicians, leaders

- Biden may lose ability to play around with Nord Stream sanctions: interview with Lana Zerkal

- Russia pushes to complete Nord Stream 2 challenging US sanctions

- Gas, money laundering, and pizza: report details Russia’s economic meddling in Europe

- Portnikov: Why Berlin saves Putin’s Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline

- Everything you wanted to know about Nord Stream 2 but were afraid to ask