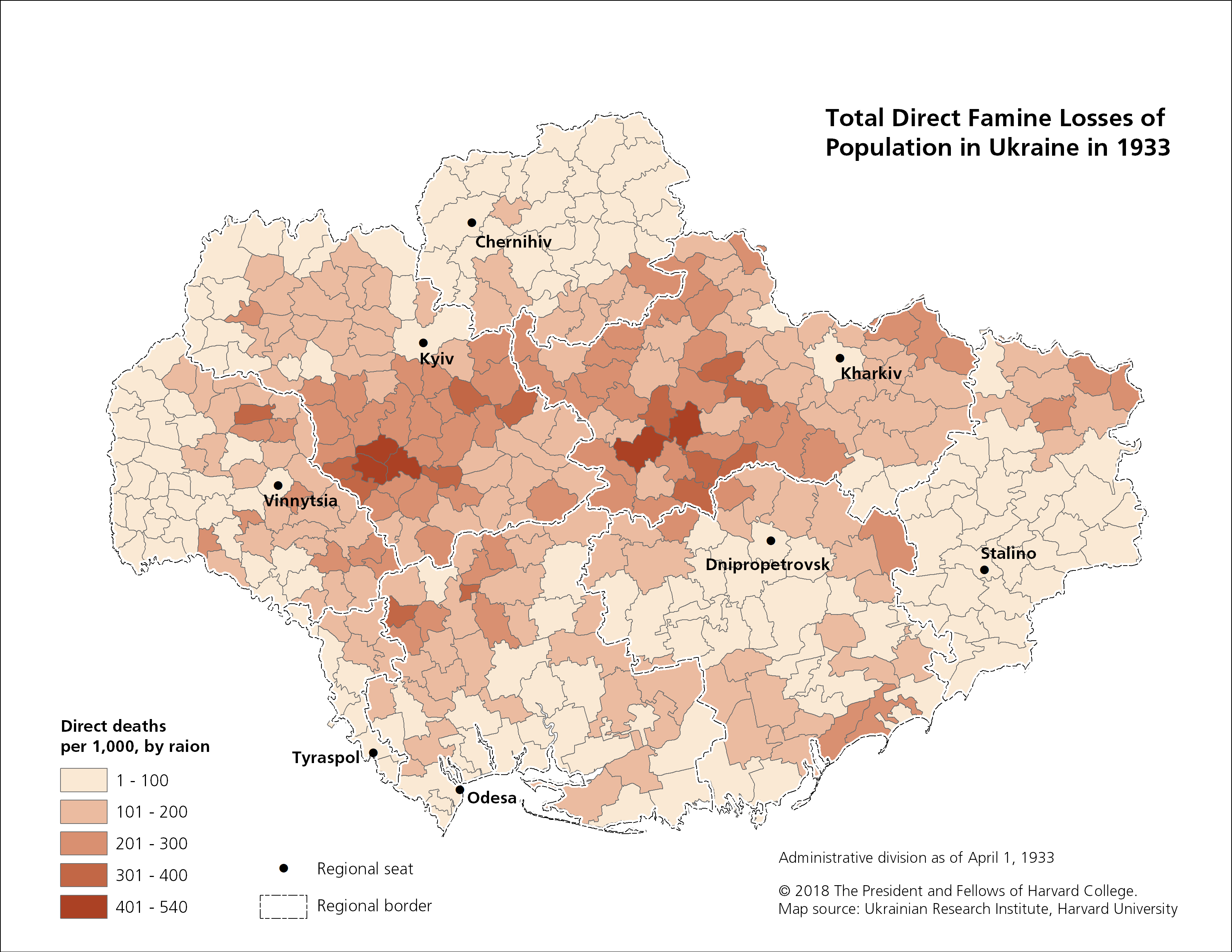

Today, November 28, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the Holodomor, man-made famine of 1932-1933 that took the lives of millions in Ukraine. Stalin's genocide against Ukrainians lasted from the spring of 1932 throughout the fall and cold winter until the spring of 1933. We don't know exactly how many Ukrainians died of starvation because the Soviet government didn't tally the deaths, however, recent estimates of historians place the death toll at 3.9 million. Ukraine observes Holodomor Remembrance Day on the fourth Saturday of November.

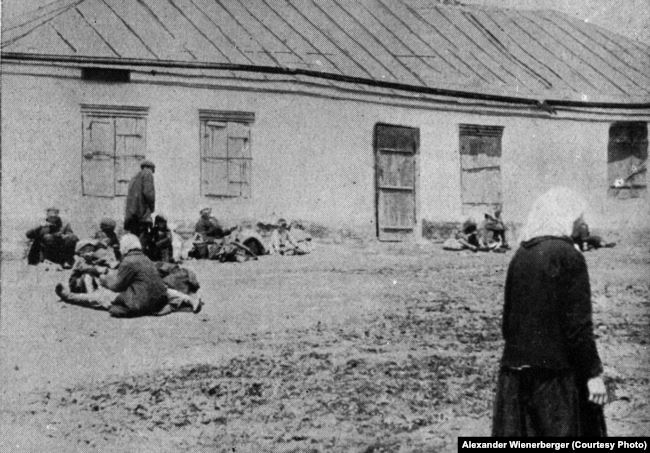

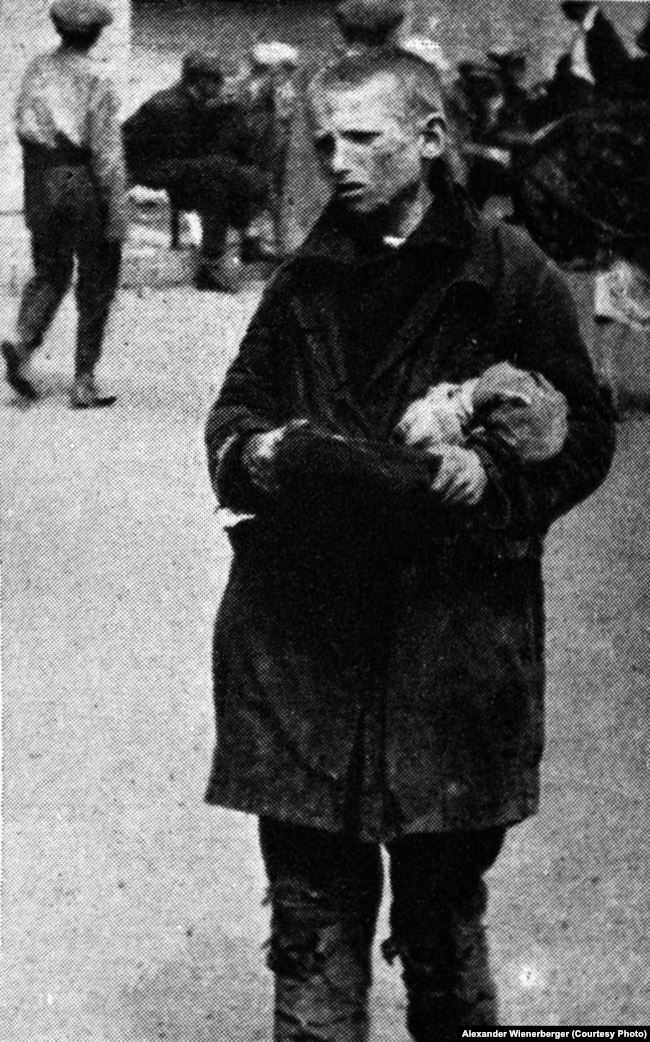

Here we publish an abridged version of Radio Svoboda's article that features previously unknown photos of the Holodomor made by Austrian engineer Alexander Wienerberger who worked in the east-Ukrainian city of Kharkiv - then capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic - in 1932-1933.

His famous photos became a horrible illustration of the artificial famine in the then capital of Soviet Ukraine, Kharkiv. Radio Liberty has discovered several more unknown photos from the Holodomor period in Wienerberger's family album, provided by the great-granddaughter of the engineer, Samara Pearce.

The material is supplemented by little-known photos and excerpts from Alexander Wienerberger's book of memoirs "Hard times. 15 years as an engineer in Soviet Russia. A True Story," published in German in 1939. Three chapters of the book are devoted to the Holodomor in Ukraine.

It was in September (1932 - ed.). I was sitting in the sleeping-car of the Moscow-Kharkiv high-speed train, which was taking me to my new job. [...] The suffering land looked even scarier during the day than at night. At each station, there were countless carriages packed with peasants and their families. They were guarded by sentries to be carried far northwards to their white death. The fields were uncultivated, the unharvested grain was rotting under the autumn rains. [...] I didn't see any cattle or even geese.

Only unkempt chickens huddled together near abandoned huts. Involuntarily, I remembered how I, a prisoner of war 17 years ago, traveled through the same country, passing wheat fields, seeing a lot of cattle and mountains of food offered at each station. Even in 1926, after the world and civil wars, these lands prospered like before. How inhuman such a force should be to turn a prosperous food-rich country into ruin. [...]

The famine was gaining momentum. In the winter (1933 - ed.), corpses of children, mostly of school age, were increasingly often found in remote places and wells. Wandering gangs were killing those unfortunates to sell their clothes at the market.

A woman buried her child who died of inanition in the cemetery. The dying child pressed a small doll to her chest. So she was buried. Two weeks later, a woman accidentally saw this doll in the market. She called the police - and everyone learned the terrible story. For months, the cemetery guard fed his pigs with corpses had a high demand for his pork. [...]

Since March 1933, Soviet newspapers had been intimidating every day that those who "sabotage" collective farms will be severely punished. The press kept repeating: if an enemy does not surrender, it will be destroyed. In early April, Soviet authorities promised Ukrainian peasants that their relatives deported to Siberia and northern Russia would be pardoned if they surrendered their fields. The authorities also promised to distribute grain for sowing.

Naive people fell into the trap. They began to cultivate the fields and thus exposed their grain stocks. Of course, they did not receive any seed. A whole army of GPU operatives (the State Political Administration - the Soviet secret service, the predecessor of the NKVD - ed.) flooded the villages. Pretending to be collecting tax debts for previous years, they confiscated the last food from hungry peasants. Ukrainians hid grain in their backyards. These food supplies were sought with bayonets. When the "workers and peasants' authorities" realized that the hungry peasants would flock to the cities, they stopped selling train tickets for six months. Those could only be obtained by government IDs. At the same time, it was forbidden to send food by rail or post across the country so that citizens could not help their relatives in the villages.

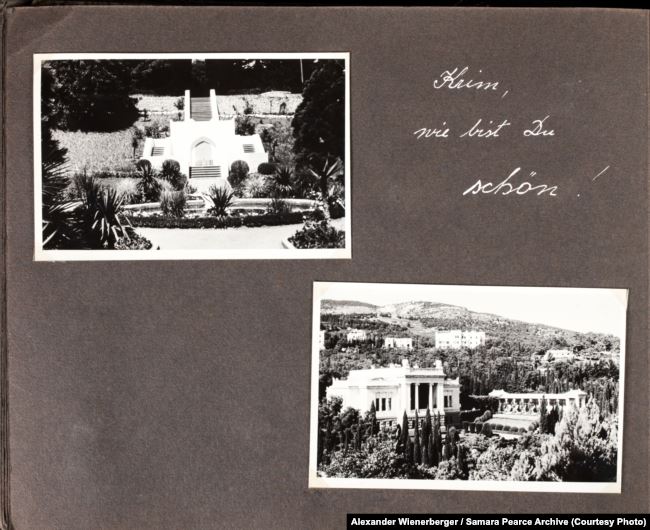

In May, I sent my wife to Crimea so that she would not see dead peasants on the streets. But very quickly she received alarming news - her sanatorium was short of food. I packed a few packages and tin cans in a bag to send to the Crimea. The Kharkiv Post Office refused to accept the parcel due to a food blockade. But they came across the wrong person. I think that the director of the post office has never heard as many curses in his life as he did then. Finally, 15 minutes later, he timidly said, “Please, dear comrade, put your things in the box. So that we won't be able to check what's inside. So we will accept your parcel with a clear conscience."

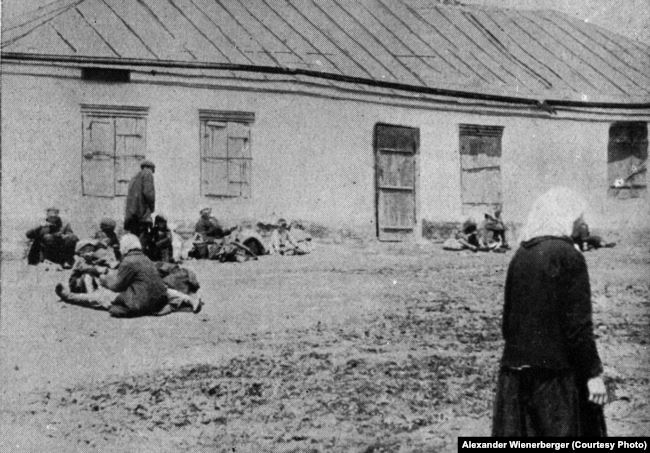

Meanwhile, the tragedy continued. Hundreds and thousands of hungry peasants were coming from afar to the city for help, bread, work, and consolation. They gathered in flocks in the streets and squares, in the city gardens and courtyards. No one drove them away, but neither did they help them.

At this time, the bread ration norms for civilians in the city were reduced to 200 grams. At the same time, the state opened several shops in Kharkiv, where you could buy a kilo of rye bread for 2.5 rubles. Long queues emerged near those shops, sometimes stretching for kilometers. People had to stand from 4 p.m. to get there only on the next day! Everyone was given a kilogram of bread. Despite the fact that the entrances and exits of these stores were secured by police, there were often bloody brawls in the queue. After all, thanks to a kilogram of bread you could live another day or two. [...]

The tragedy continued. More and more peasants appeared to sell their last shirt, and the brawls in shops were becoming more violent. The bread was constantly rising in price and cost up to 12 rubles per kilogram at the market.

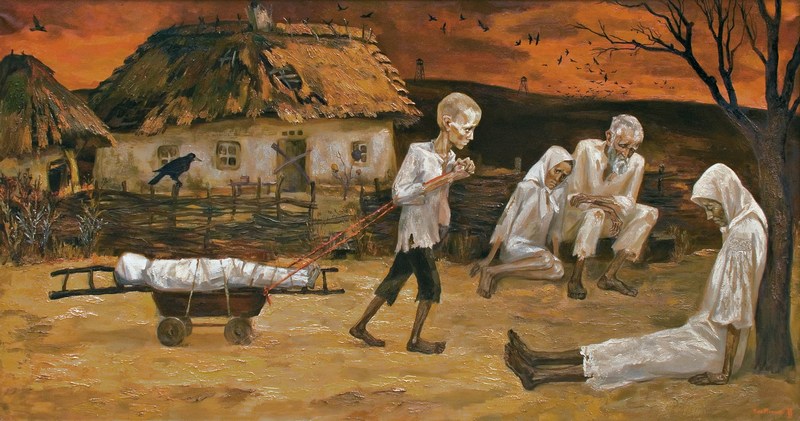

At the same time, violent epidemics of typhus and dysentery began, which quickly took over the exhausted bodies. People died en masse in the streets. Their hands, swollen with hunger, stiffened begging for alms. First men died, then women, and finally children, poor, innocent creatures.

"Stalin is building a pyramid of Cheops from human skulls," said my new assistant at the plant, a Ukrainian engineer with whom I sometimes dared to exchange words.

One day I happened to go with the director Katz to the plant Chim. On the road, near our factory, a woman laid with a baby (I noticed her in the morning). I just had a flat tire, so I stopped just before this misfortune. The woman was already dead, lice were crawling on her. The toddler cried pitifully from hunger. The director glanced at me.

"Would you be so kind as to take the child to the police?" He finally replied after I silently fixed my eyes on him.

"Gladly," I replied, wrapping the child in burlap and taking him to the orphanage. They were not very happy there with the new addition. But, inspired by this case, I saved a few more dozens of such unfortunates from certain death.

The city authorities were visibly confused by the bodies laying literally everywhere. Apparently, Moscow ordered not to help the hungry peasants but did not explain what to do with the victims of Stalin's mass death sentence. At first, they buried the bodies on the spot, in gardens and in backyards. But the number of corpses increased. Trucks worked twice a day, in the evening and at dawn, to collect "human stuff," as Katz called it, and take it to mass graves on the outskirts of the city.

The convicts dug graves. There were seven such mass cemeteries, about 250 pits in each. A pit housed 15 bodies. Add to this the people buried outside the cemeteries, and it is easy to see that about 30,000 people - men, women, and children - are buried in Kharkiv alone.

Seeing the corpses being collected on the street makes blood freeze. Dead babies were snatched away from their mothers who were howling in pain. Living babies were taken from the dry breasts of speechless and dead mothers. The children were shouting and moaning. The old people held out their bony wrinkled hands with their eyes clouded with terror. One woman whose dead toddler was taken away lamented that she should be buried with the baby. An unfriendly medical worker smiled sarcastically at her,

"In the evening, mother, you'll be ready, then we'll take you too." […]

Before my eyes, again, there is a Ukrainian village where I went in the spring of 1933 in search of casein (the main protein component of milk used to produce plastics, paints, glues, artificial fibers - ed.). I have no words to describe this horror I saw.

Half of the houses were empty, lonesome horses plucked straw from the roofs. But the horses soon died too. There were no dogs or cats, just a bunch of rats gnawing at the exhausted corpses lying around in broad daylight. The survivors no longer had the energy to bury their dead. Cannibalism was commonplace. The authorities did not react to this in any way.

In an abandoned garden near the house, parents buried their child in the frozen ground. The pit was dug shallow. Hunger soon killed the parents too. The snow melted, and two dead children's hands stretched out from under the ground to the sky, as if asking God for revenge on the perpetrators of this unspeakable grief. […]

Scanned copies of photographs by Alexander Wienerberger from his book "Hart auf hart. 15 Jahre Ingenieur in Sowjetrußland. Ein Tatsachenbericht, Salzburg 1939” were provided by the American researcher Lana Babiy.

Comments to the photo were provided by Lana Babiy and Kharkiv historian Ihor Shuiskyi.

Read more:

- Ukrainian Holodomor Museum launches crowdfunding campaign to create main exhibition

- Holodomor survivor stories come to life in mobile app for tourists

- Bread from tree bark and straw: students launch online “restaurant” with Holodomor "recipes"

- Stalin’s anti-Ukrainian policies in RSFSR prove Holodomor was a genocide

- Stalin’s management of Red Army proves Holodomor a Soviet genocide against Ukrainians

- Holodomor: Stalin’s punishment for 5,000 peasant revolts

- “Let me take the wife too, when I reach the cemetery she will be dead.” Stories of Holodomor survivors