The Chief Rabbi states that he bases his arguments on strong historical facts, namely that during the Third Reich’s systematic persecution and execution of the Jewish population in Western Ukraine, Andrei Sheptytsky rescued more than 150 Jewish children who were hidden in monasteries and convents on his orders.

The letter:

Addressed to: Avner Shalev, Chairman of the Yad Vashem Directorate of the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority

On the eve of International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp (January 27), I hereby call on you to restore historical justice with regard to Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky.

Metropolitan Andrei rescued more than 150 Jewish children during the Holocaust in Western Ukraine. Not only did he command churches and monasteries to hide these children, but he also did not allow them to be baptized, thus saving them for the Jewish nation. Some of these children are still alive today. I have read their testimonies, where they all acknowledge their deep debt to Andrei Sheptytsky.

The situation is indeed absurd: Andrei’s younger brother, Archimandrite Klymentiy Sheptytsky and Mother Superior Olena Viter, both of whom obeyed Metropolitan Andrei’s direct orders related to the Jewish children, were awarded the honorific title of “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem, whereas the Metropolitan, who was in charge of all these extremely dangerous operations, has never been recognized.

The arguments against the Metropolitan are well-known: first, his telegram welcoming Hitler and the Wehrmacht to Lviv in 1941 and second, his alleged “blessing” of the SS Galicia Division in 1943. The telegram was written just after the horrifying discovery in Lviv prisons of hundreds of Ukrainians, executed by the retreating Stalinist criminals. In Sheptytsky’s eyes, the Soviet regime was cruel and godless. Moreover, as protector of his flock and the church, Sheptytsky also sent similar greetings to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia when the Russian army occupied Lviv in 1914 and to Stalin in 1939.

When viewing events in their historical context, what should be more important? 150 children rescued from certain death or some telegrams addressed to the Fuhrer?

During the first year of Nazi occupation, Metropolitan Andrei wrote several letters to the Vatican, stating that the Nazi regime was committing atrocities that even surpassed Stalin’s crimes. In his 1942 pastoral letter “Do Not Kill!”, Sheptytsky exhorted his faithful to respect their neighbours and refrain from taking part in any form of killing or murder. The Metropolitan also sent a telegram to Himmler demanding that the Nazi occupation troops stop forcing Ukrainians to participate in barbaric acts. This was indeed a very risky statement to make at that time!

There are no historic documents confirming Sheptytsky’s alleged “blessing” of the SS Galicia Division. In fact, the Metropolitan gave one of his priest permission to act as chaplain in the division in order to watch over the young recruits and prevent them from committing excessive crimes.

Any other stories and tales are just myths and stereotypes invented by the Soviet regime to discredit Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky. I firmly believe that it is high time for modern Israel and the Jewish Diaspora to abandon these old myths.

During the hellish years of the Holocaust, the figure of Andrei Sheptytsky rises above all others, like a strong rock of human goodness and salvation. Metropolitan Andrei was a giant of humanism and one of the greatest Ukrainian personalities of the 20th century. His work and cooperation with the Jewish population lasted dozens of years.

The fact that Metropolitan Andrei has not been awarded this honorific title is indeed a gross miscarriage of justice. According to Jewish traditions, we must express our sincere gratitude for any acts of kindness and goodness extended to the Jewish nation. Therefore, by granting Metropolitan Andrei the honorific title of “Righteous Among the Nations”, Israel will show Ukraine and the world that the Jewish nation respects and remembers its friends and saviours.

My duty as Chief Rabbi of Kyiv and Ukraine and my deep conviction as a human being is to raise my voice in defense of a great humanist and friend of the Jewish people, Andrei Sheptytsky. For some years now, our community has recognized this fact and a tree has been planted in his honour near the Brodsky Choral Synagogue in Kyiv.

In conclusion, we hereby call on you and Yad Vashem to review the candidature of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky for the honorific title of “Righteous Among the Nations”.

With our blessings,

Respectfully yours,

Chief Rabbi of Ukraine, Moshe Reuven Azman

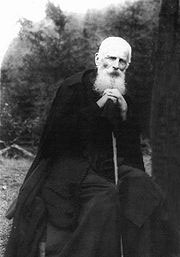

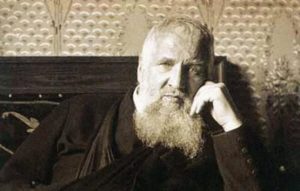

Andrei Sheptytsky

Born July 29, 1865 in Prylbychi, Yavoriv County, Halychyna (Galicia); died November 1, 1944 in Lviv. Religious, cultural, and civic figure; Metropolitan of Halych, Archbishop of Lviv and Bishop of Kamianets-Podilsky.

Andrei Sheptytsky was born in a prominent Ukrainian-Polish noble family, which included several influential Ukrainian Greek-Catholic churchmen on his father’s side, and the Fredros, a prominent Polish family on his mother’s side. In August 1892, after finishing his theological training, he was ordainedand and then completed his studies in law at the University of Krakow, and in theology and philosophy at the Jesuit Seminary in Krakow.

During the Russian occupations of Galicia during World War I, Sheptytsky was arrested in September 1914 and deported. Distrusted by the tsarist government for his Austro-Hungarian loyalties, missionary Catholic zeal, and high standing among the Ukrainian population, he was detained several times before being released after the February Revolution of 1917. He then traveled briefly to Petrograd and Kyiv, where he met with members of the Central Rada.

After his return to Lviv in September 1917, Sheptytsky engaged in church affairs and the Ukrainian fight for independence (1917-20).

World War 2 was a difficult time for Sheptytsky and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. During the first Soviet occupation of Western Ukraine (1939–41), he remained in Lviv and defended his church and flock; he issued several pastoral letters exhorting his faithful to resist the atheism imposed by the regime. Although much church property was confiscated and most religious schools and other institutions were closed down, the authorities did not harm Metropolitan Andrei because of his prominence and recognized authority.

In early 1942, Sheptytsky sent a letter to Heinrich Himmler protesting Nazi treatment of the Jews and the use of Ukrainians in anti-Jewish repressions. He also began to provide refuge to Jews, hiding them from the Nazis and instructed his monasteries and convents to do the same. In November 1942, he issued a strong pastoral letter denouncing all killing, including the politically motivated assassinations carried out by different Ukrainian parties. He remained active in Ukrainian political life throughout the war despite his failing health, and attempted to mediate between competing factions and to come to an understanding with Ukrainian church leaders.

After the Soviets occupied Western Ukraine again in 1944, Metropolitan Andrei remained in Lviv in order to preserve the church and his flock. Soviet attacks on the church were moderate until his death because of his great authority. His momentous public funeral was attended by thousands of Ukrainians, but his death greatly weakened the position of the Greek Catholic Church, which was banned by Stalin’s plan of April 1945 and went underground until its resurrection in 1991.