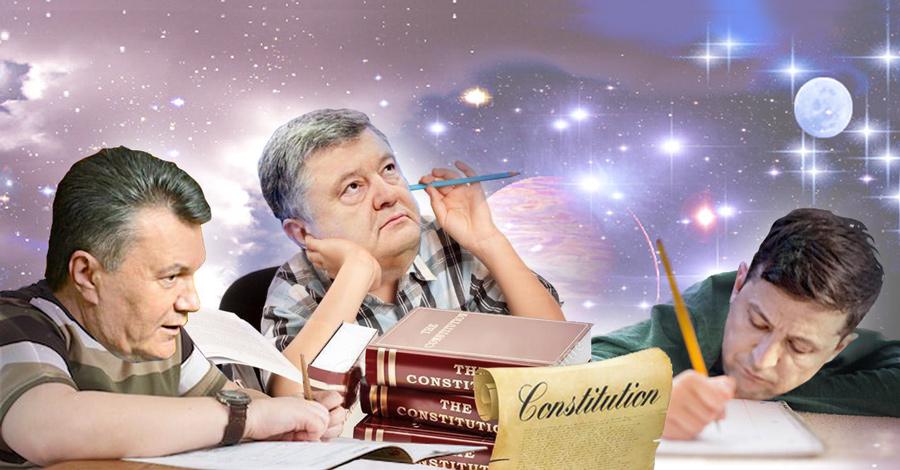

Three alterations to the Ukrainian constitution mirrored each other. They transferred several powers from the president to the parliament when Viktor Yushchenko came to power in 2005, then back to the president with Viktor Yanukovych’s rule and, finally, again to the parliament after the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. The assignation of ministers and the general control over the cabinet and executives was a subject to this tug-of-war between the parliaments and the presidents.

The brand-new president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, is not trying to gain control over executives by changing the constitution. He doesn’t need to since his party has the overwhelming majority in the parliament and follows his will regarding all cabinet appointments. Instead, the President has proposed seven other amendments.

What Zelenskyy is changing in the Constitution

1. Lifting parliamentarian immunity. Amendments to Constitution's Article 80 have been approved in the second reading. Starting from 2020, members of the parliament can be arrested and convicted without any consent from the parliament, required under the current legislation.

This amendment was submitted by then-president Petro Poroshenko as it was among the key popular demands, but he delayed the final voting. Yet the decision to lift the MP immunity was rather populist than reasonable. Ukrainians like it because they simply dislike any authorities. However, a certain degree of immunity is preserved even in democracies as strong as the USA so that courts and security officers controlled by other branches of power could not exert any pressure on the parliament. The possibility that any court in the country, even the lowest, can convict a parliamentarian is hardly the best idea.

Criticizing this amendment, Serhiy Hrabovskyi, Ukrainian writer and social scientist, appeals to the Estonian legislature, where the constitution guarantees quite a strong degree of immunity for people’s deputies,

“Members of the State Assembly are protected from prosecution. Criminal liability against them can only be instituted upon the submission of the Chancellor of Justice with the consent of the majority of the members of the State Assembly.”

2. President takes powers to appoint directors of National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) and the State Bureau of Investigation (DBR) away from parliament. This has attracted considerable public attention, but the change is rather insignificant, as the directors of both institutions get selected by special commissions and their appointment is a formality. the procedure described in relevant laws. However, if the law on the commissions is also amended - a scenario that is all too likely with Zelenskyy's Servant of the People holding a single-party majority, then the powers of the president may rise significantly.

3. More disturbing is the amendment conferring the president a right “to create independent regulatory institutions that carry out state regulation, monitoring, and control over the activity of economic entities in particular areas, appoint and dismiss their members…” What kind of institutions are these? What about the deregulation of the economy announced in Zelenskyy's electoral program? Finally, why does the president need control over the economy which is the responsibility of the cabinet? There are no answers yet.

4. Another amendment rescinds the monopoly of advocacy in court under which only a lawyer is allowed to represent the defendant's interests. This norm was written into the Constitution as part of judiciary reform by previous authorities. The cancelation of this is quite dubious. On the one hand, critics from the Association of Lawyers of Ukraine state that the amendment will lower the professional level of court hearings. It is world practice that lawyers should obtain a license from the state to maintain a standard of the work and carry responsibility for their actions. On the other hand, in Ukraine's case, the process of issuing licenses was totally corrupt. Therefore, the amendment may liberalize the market of judiciary services and stop corruption. At the same time, instead of canceling the licensing, the system of their issuance could be reformed.

5. More popular consensus exists regarding the amendment according to which deputies should be deprived of their mandate in case they skip more than one-third of parliamentarian sessions or if they vote for their colleagues [the phenomenon, known as "piano voting" when a Rada deputy votes several times by using own identity card and ones belonging to other deputies; such an MP is called a knopkodav "button pusher" in the Ukrainian political slang, - Ed.]. If the amendment succeeds, courts will be able to unseat such people's deputies. However, given that the MPs were totally stripped of immunity and the president's influence over law enforcement, these changes could become an instrument for pressuring the MPs.

6. Reducing the number of people’s deputies from 450 to 300 and enshrining a proportional election system. The first part could be seen as reasonable, as the Ukrainian population has also decreased. However, in many European countries, the proportion of of MPs relative to the population is much higher than in Ukraine, and it is unclear whether this will improve the work of parliament, so this can be seen as a populist move. Regarding the proportional election system, it's unclear why the amendment does not mention open party lists, a requirement which experts see as essential, and which is included in the new Election Code.

7. The amendment ves} the ting people with a right to propose draft laws to the parliament creates an even more populist impression. The amendment remains unrealistic until a relevant law is adopted to specify the procedure of submitting and accepting such bills. Also, there already is a mechanism of submitting petitions to the parliament. What difference this new initiative will make compared to the already existing petitioning is not clear. Ex-president Petro Poroshenko's European Solidarity and Sviatoslav Vakarchuk's Voice voted against the amendment, claiming that the law-to-be adopted for this amendment may limit parliamentary powers even further.

Tiptoeing to superpresidentialism?

The amendments proposed by Zelenskyy are far less radically pro-presidential than Yanukovych’s. Nonetheless, some critics and political opponents warn that Zelenskyy is tiptoeing to superpresidentialism quietly, step by step.

They point at the manner how Zelenskyy treats the parliamentarians as if his party are merely his employees. While the newly elected Verkhovna Rada endorsed a bill to abolish the immunity of the people's deputies, weakening itself, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy repeatedly urged the deputies to vote: "Let's go," and "Dmitry [Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada - Ed.], continue."

Also telling was was the way Zelenkyy instructed the cabinet. Although the cabinet is a separate government body appointed exclusively by the parliament with only a few presidential nominations, Zelenskyy behaves as if ministers are by far his employees due to control over the majority in the parliament.

Taking all this into account, political opponents say that superpresidentialism can indeed emerge in Ukraine. For example, the head of the Holos party Serhiy Rakhmanin appealed to fellow MPs as follows:

“I may have read president Zelenskyy's election program inattentively, but I don't remember him promising to boost his powers... Looking at some changes, constitutional and legislative, he is going to subordinate all the military and enforcement structures, starting with the National Guard and ending up with the possibility of creating an unlimited number of regulatory institutions. It seems to me that I missed some episodes of The Servant of the People."

Serhiy Rakhmanin argued that if the Rada was going to annul parliamentarian immunity, then it should simultaneously amend the legislature on presidential impeachment. Although the Rada did adopt a bill on impeachment on 10 September, experts have criticized it as populist - applying it will be all but impossible for any Ukrainian president, much less Zelenskyy with single-party majority.

However, it is too late to limit Zelenskyy in any way. Due to the landslide results in both parliamentary and presidential elections, his team is already ruling on its own. Whether he takes some responsibilities away from the parliament or not, his power remains virtually unlimited unless the deputies from his party turn against him, which is an unlikely scenario.

Two fundamental issues in the Ukrainian political system

There are two essential issues of the political system in Ukraine enshrined in the Constitution and commonly criticized by political scientists.

First, the presidential and parliamentarian powers partially overlap. Although the cabinet is appointed mainly by the parliament, it is controlled by the president as well. This creates instability and inner conflicts between the president and the parliament that results in an everlasting amending of the fundamental law. Meanwhile, in case the president’s party gains a majority in the Verkhovna Rada, the president attains de-facto unlimited power. And the instability in the political system begets semi-authoritarianism in this way.

The situation gets even worse because the constitutional court controlling both the president and parliament is appointed by ⅔ by the president and parliament. This is the second problem that makes any control barely possible. No politician has dared to seriously question this issue of the Ukrainian political system yet.

Vsevolod Rechytskyi: Ukrainian constitution lacks the spirit of capitalism

So why were these instability drivers written into the Ukrainian constitution? Vsevolod Rechytskyi, Ukrainian lawyer and political scientist, gives a very clear answer in a number of his articles for Krytyka magazine.

He claims that according to the vision of America’s founding fathers as the authors of the first democratic constitution in the world, the constitution should establish the freedom of the people as the highest value. In the American political tradition, the constitution serves, first of all, as a basis for protecting individual rights, including private property and freedom of speech. Only then does it serve to outline the political system of the country.

“As for contemporary European constitutionalism," he claims, "It looks a bit weakened... version of the American constitutional approach... In America, businesses can be opened in 6 hours, while in Europe in several days or even weeks... Western Europeans, no matter how unfortunate it may sound, still do not dare to be as consistent and bold in their creative pursuits as their political partners across the Atlantic.”

The Ukrainian constitution, however, is yet more twisted by socialist ideas.

“Already in the work on the final draft of the Constitution of Ukraine in February 1996," the researcher describes, "At an international conference in Guta, some lawyers tried to draw attention… to the fact that freedom of the people was not declared in the text of the Basic Law. Unfortunately, despite all the caveats of progressive lawyers, our constitutional process has gone the other way… In the final draft version of the Basic Law of Ukraine, the members of the Working Group of the Constitutional Commission wrote that in Ukraine the highest social value is not the freedom of the people, but a person, their life and health… The paradox of this situation is that... we have a big problem with the average life expectancy of men and women.”

Vsevolod Rechytskyi claims that the constitution is a document that is necessary and makes sense only for the capitalist system of free self-responsible individuals to protect their rights from the state. In that case, the constitution becomes the document important for the freedom of each person.

However, in such countries as Ukraine, the constitution reflects the instability of unfinished capitalism. People for whom personal freedom and private property is not the highest value but a social wealth, do not need a constitution to protect their rights from the authorities.

In such a system, what is termed constitution has a totally different function - to redistribute the power between three branches and define who is responsible for establishing people’s wealth right now. Such a constitution is changing all the time according to the situation because it has few eternal values to protect.

“The US Constitution, begotten by classical capitalism, absorbed its basic normative requirements," Vsevolod Rechytskyi concludes in his article, "And since then free enterprise and the US Constitution have been elements of an inseparable civilizational reality."

The difference in the Ukrainian and American versions of constitutionalism can also be noticed by comparing the content of the oath of the US and Ukrainian presidents. In the US, the presidential oath reads as follows:

"I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

The Ukrainian oath is longer:

"I, by the will of the people, elected as a President of Ukraine, taking this high position, solemnly swear allegiance to Ukraine. I pledge to defend the sovereignty and independence of Ukraine by all my deeds, to care for the good of the Fatherland and the wealth of the Ukrainian people, to uphold the rights and freedoms of citizens, to abide by the Constitution of Ukraine and the laws of Ukraine, to fulfill my duties in the interests of all compatriots, to raise the authority of Ukraine in the world."

Mr. Rechytskyi notes, "The US President is given the role of a modest promoter of the Basic Law, the Ukrainian is almost a patron saint of the nation." With seemingly two similar normative instruments, the American model of constitutionalism implies the formula "rule of law," while Ukraine's formula is "rule by law." "In the second case, the law is not a restriction of power, but an auxiliary legal instrument,” stresses the political scientist.

Vsevolod Rechytskyi makes a twofold conclusion: de jure Ukraine should embed personal freedom as the central value of the constitution and private property as the central goal of political system; on the other hand, the government should facilitate the real importance and value of private property by deregulations, opening of the agricultural land market, etc so that the constitution will attain personal and immutable meaning for people.

Read also:

- Death of the Parliamentary Republic in Ukraine

- What Zelenskyy’s prophetic “Servant of the People” TV show suggests for his further steps

- Ukraine’s new Parliament violates regulations in its strong will to serve the people

- Ukraine’s new Cabinet: new faces, merged ministries, and the immortal Avakov

- Judicial reform 2.0: Zelenskyy comes with initiatives only partly supported by society

- Zelenskyy’s first 100 days

- Portnikov: Ukraine’s development will resume after crisis caused by Zelenskyy

- Oligarch interests in the new Ukrainian parliament

- Will Zelenskyy aim for even more power via snap local elections?

- Zelenskyy’s consolidation of power: a chance for change or authoritarianism?

- Zelenskyy to form mono coalition and other takeaways of Ukrainian elections

- Power of TV still rules Ukrainian politics, presidential election shows

- Ukrainian civil society outlines “red lines” President Zelenskyy can’t cross

- Zelenskyy’s first appointments: Kolomoiskyi’s lawyer, cronies, experts

- How Zelenskyy “hacked” Ukraine’s elections | Op-ed

- What’s behind the return of pro-Russian politicians to Ukraine?