International polling, such as Pew’s 2018 research, has been proving the failure of Russian “soft power” since Russia invaded Crimea in 2014. According to Pew, just 34% and 26% of the global public (covering 25 countries) expressed a favourable view of Russia or President Putin respectively. Similarly, only a fraction of the population of the V4 countries (3-13%) would consider themselves as “part of the East” culturally or politically based on the Globsec Trends 2018 data in Central-Eastern Europe. So, we can quite confidently say that Russian “soft power” or the “weaponization of culture” that relies on cultural and political appeal, the beauty of Mother Russia’s landscapes etc. is failing, despite the Kremlin’s expansive and expensive international media empire (RT, Sputnik) and their local media clones’ presence in Europe.

The rise of Russia’s “sharp power”

Instead, our research proved the significance of the Kremlin’s so-called “sharp power,” one’s ability to influence and manipulate the geopolitical perceptions of foreign target audiences through feeding them negative or positive messages, disinformation.

Political Capital’s big data research in cooperation with Bakamo.Social has revealed that the formula has worked excellently in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia. An explicit aim of the research was to leave behind the “elitist,” top-down approach of analyses on hybrid warfare and investigate ordinary conversations, so BakamoSocial’s social listening methodology mapped millions of “natural,” spontaneous online conversations of average citizens related to Russia or the Kremlin in a two-year period (between 20 November 2016 and 19 November 2018).

Based on our research data, the Kremlin’s perceived international “omnipotence” could be confirmed by “folk perceptions” in the three countries under revision. Although, the majority of online conversations related to Russia were either negative (46% of messages) or neutral (33% of messages), the two leading views in each country attributed direct and unrealistic influence to the Kremlin as a military “aggressor” or an “invisible manipulator,” capable to spying on people and/or changing their minds on certain issues.

Hungarian people seemed to be the most charmed by Russian influence and looking to the Kremlin as a “strong protector” (10%), which reflects the positive and uncritical approach of the Hungarian government to Hungarian-Russian bilateral relations. Moreover, we could identify “consumer groups” of Russia-related news or disinformation.

Around the third or 30% of each society belongs to three pro-Russian consumer groups or public segments with markedly different profiles in their relation to Russian sharp power.

” (10% of the sample) is receptive primarily to the masculinity and militarism of the Kremlin and Vladimir Putin; the group of “admirers of Russia” (10%) is more interested in high culture and the Soviet legacy. The third consumer group with positive attitudes was labeled “Russia is the safer bet than the West” (8%). They interpret Russia’ role in pragmatic economic and political terms based on Russia’s geopolitical proximity and economic or military power, so they provide a fertile ground for anti-sanctions rhetoric.

Russian fanboys are easily found among Eastern European and European far-right parties or paramilitary organizations maintaining excellent political relations with the Kremlin, while Soviet nostalgia is typically present among the older generations who spent their youth in the communist era and were especially hard hit by the economic outfall of the democratic transitions in the 1990s.

We also revealed a regional or Central-European pattern and basic drivers of the Russian sharp power. Foreign authoritarian influence in the CEE is strengthened by three main societal factors connected to the region’s geopolitical crisis.

Russian sharp power in the European elections

The monitoring

of the current European elections campaign (by Political Capital, Globsec Policy Institute and Prague Security Studies Institute) has proven the interplay of these drivers of Russian sharp power.

On the one hand, disinformation framed the European Union as some sort of a non-democratic “monster” crushing national identities, for instance, Sputnik CZ quoted SPD representative Radim Fiala’ parallel between the EU and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, or forcing Hungarians to abandon their Christian faith and traditions in favour of Muslim mass migration allegedly “enabled” by Brussels.

On the other hand, the Kremlin clearly supported the new far-right and pro-Russian political group titled Alliance of Peoples and Nations (EAPN) to be established by Matteo Salvini (League Party) and Marine Le Pen (National Rally Party) in the new European Parliament – an initiative that would welcome PM Orbán and his Fidesz-KDNP ruling coalition as well. Different narratives about the Union’s responsibility for immigration and related conspiracy theories all contribute to the EU’s negative issues, as seen on the chart below.

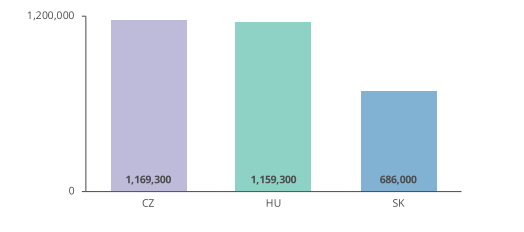

While anti-Russian attitudes and narratives are still dominating the political discourses in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary, research pointed to the fragility of this kind of societal resilience to Russian sharp power. Russia’s image is shaped by a relatively small minority of active users that amount to only 30-60,000 users or opinion leaders in each of the three countries we examined. Consequently, it would take only a small effort to fundamentally change the current anti-Russian perceptions in the CEE. More importantly, Russian sharp power already has the ability to circumvent the official communication channels via the existing, strong pro-Russian discussions and consumer groups on the grassroots levels of everyday communication.

Disclaimer

The authors are grateful for the generous support of the National Endowment for Democracy that made these researches possible. For more on Russian sharp power in the CEE see Political Capital’s dedicated website.

, disinformation, and populism in Europe.

Read also: