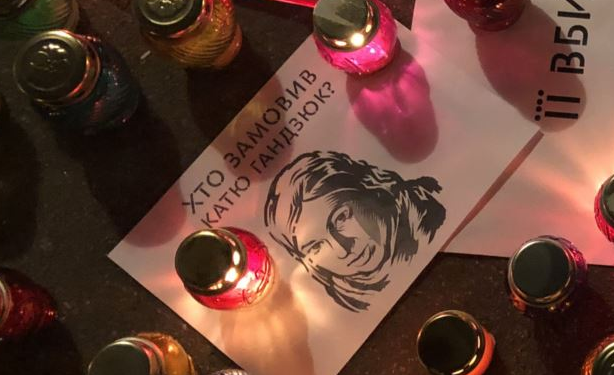

The death of Ukrainian activist Kateryna Handziuk on her hospital bed on 4 November 2018 spurred nation-wide outrage. Hundreds rallied all over the country, demanding an effective investigation into the acid attack which after three months of attempts at treatment took the life of the 34-year old Kherson activist and city official, and 73 human rights organizations signed a collective appeal calling upon Prosecutor General Yuriy Lutsenko and Minister of Interior Arsen Avakov, "who sabotaged the law enforcement reform in Ukraine," to resign.

Read more: Ukrainian activist attacked with acid dies in hospital. Mandator of murder still not found

Yuriy Lutsenko appeared to adhere to this call and announced he is ready to step down. However, this intention soon turned farcical as the parliamentary coalition announced it would not support the resignation, which predictably failed to be voted through. The calls on him and Avakov to resign came because Kateryna's fatal acid attack is one of the latest in a string of assaults on civic activists all over Ukraine - at least 55 since 2017. Human rights defenders say one of the reasons for them is the incapability of Ukraine's law enforcement to conduct an effective investigation. There are also suspicions of the law enforcement being in cahoots with the attackers and sabotaging the investigations.

Read more: Epidemic of attacks on activists in Ukraine – result of aborted police reform

On the insistence of MP Mustafa Nayyem, a temporary parliamentary commission of 18 MPs was formed in order to analyze the results of investigations on civic activists. However, Yuriy Lutsenko announced it will not receive any information from the investigation. Handziuk's laywer Yevheniya Zakrevska also said she will do what she can to prevent the investigation's data from reaching the commission, as the latter includes Narodnyi Front MP Anton Herashchenko, a comrade-in-arms of Interior Minister Arsen Avakov. Zakrevska says Herashchenko regularly publicized pre-trial investigation data before it was shared with her client and that his presence in the commission is an "insult to the memory of Handziuk."

Currently, five people have been detained on suspicion of carrying out the attack; of them, one, Serhiy Torbin, is suspected of being the organizer. The Head of the National Police Serhiy Kniazev reported that based on their investigation thus far, the suspects first planned to beat up Handziuk for a reward of $5,000 (for all five) but then decided to douse her with sulphuric acid instead. All five are veterans of the war in Donbas.

However, the ultimate mandator of the murder is unknown and Kateryna's friends worry he never will be. Yuriy Lutsenko informed about 12 possible suspects in the murder, but Kateryna's friends have little trust in official versions. The reason for this is the police's initial classification of the attempt at murder as hooliganism and the investigation's eagerness to pin down the crime on a first random suspect who was rescued only thanks to the interference of journalists who made public his alibi. Thus, activists and journalists are scouring the issue in parallel to the official investigation and are pointing at Ihor Pavlovskyi, assistant to Poroshenko Bloc MP Mykola Palamarchuk.

While we are waiting for further developments, let's look into who Kateryna was and what she did to become one of the most famous civic activists of southern Ukraine.

What follows is an adapted translation from Inna Semenova's article on NV.

Civic activity

Kateryna Handziuk was a civic activist for many years. During her studies at the Kherson state university she took part in the Orange revolution of 2004, and during the Euromaidan Revolution, she was one of the most prominent participants of the protests in Kherson. For some time she headed the youth wing of the Batkivshchyna party, but in 2015 left it in solidarity with Kherson mayor Volodymyr Mykolaienko, who was expelled from the party. In her last years, Handziuk combined her activism with being an advisor to the Kherson mayor and holding a position at the Kherson city council.

Journalist investigations

Together with Kherson journalist Serhiy Nikitenko, who was also attacked in 2018, Handziuk co-founded the Agency of civic journalism Mist and the website most.ks.ua. Starting from 2012, the portal became one of the key internet media in Kherson, focusing on local politics, particularly on monitoring state procurements and expenditures of state money, as well as anti-corruption investigations.

Fighting separatist movements in Kherson

In her last years, Handziuk focused on resisting pro-Russian movements in Kherson. Starting from 2014 and the first months of conflict in eastern Ukraine, she resisted Russia's attempts to spread separatist activity to Kherson Oblast. [Editor's note: Kherson was one of the cities relatively spared from separatist movements in south-eastern Ukraine during Russia's attempts to implement the 'Novorossiya' project to break off south-eastern Ukraine in the wake of the Euromaidan revolution and Russia's occupation of Crimea.]

In 2018, Handziuk publicized documents proving that representatives of pro-Russian powers illegally provide paid administrative services in the city, issuing certificates with stamped seals. She claimed that these people are the same ones who gathered rallies calling for a Russian invasion in 2014 and recruited mercenaries into terrorist detachments of Russia's puppet "republics" in eastern Ukraine.

As well, Handziuk was part of the volunteer group Itchy Trigger Finger Ukrainians, which placed patriotic ads on billboards next to the border between Ukraine and occupied Crimea.

Confrontation with the regional law enforcement

An integral part of Handziuk's struggle against local manifestations of separatism was her conflict with the law enforcement agencies of the Kherson Oblast. The activist repeatedly and rigorously blamed the security forces for their inaction in combating pro-Russian separatism, as well as in insufficient efforts to investigate the attacks on Kherson activists and corruption.

In 2017, head of the Kherson police department of economic security Artem Antoshchuk sued Handziuk after she accused him of extorting bribes from city council officials.

"It's an axiom for the department of economic security that the city authorities steal 30% of the budget funds. According to Artem, they are distributed among all of us proportionally. But don't you think that Artem is worried about the outrage of a possible embezzlement of state funds. Artem insists he is given his 3%. Until he gets these 3%, he threatens to interrogate to death, via dummy cases, all those who don't pay up the tribute," told Handziuk, who was managing the affairs of the executive committee of the Kherson City.

Antoshchuk filed a lawsuit against Hendziuk to protect his honor and dignity, but the court rejected most of his claims and charges.

In July 2018, Handziuk criticized the security forces for their inaction in investigating an attack on her colleague, the journalist-investigator Serhiy Nikitenko.

"It took 32 days for the Kherson boys-in-blue to uncover that Serhiy was a journalist, I'm not joking, 32 (thirty-two). Now the investigation has risen to a new level: they are looking for witnesses of the event on Facebook," Handziuk wrote sarcastically on her Fb page. "I think by the year 3019, you can assign the guilt to some drug addict because no sane person believes you are seriously looking for anybody there."

And in April 2018, Handziuk released information that some 200 "journalists" with fake identity cards received permission from the regional police for traumatic and gun weapons in 2014-2018. "Nice business the barneys have there, huh?" she commented.

Volunteering

Kateryna Handziuk was also known for her multifaceted volunteer activities. She widely cooperated with the UN - for instance, in 2012, she worked in a UN development program project to develop football volunteering for youth engagement. In this project, Handziuk worked to develop sports activities in village regions of the Kherson Oblast, working with schoolchildren and school football teachers.

Additionally, with the start of the war in Donbas, Handziuk took part in programs to help IDPs from eastern Ukraine. She worked as a Legal Assistant to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in Kherson Oblast and organized fundraising campaigns for children of IDPs.

Read also:

- Attacks on civic activists in Ukraine reaching critical level, encouraged by unreformed police

- Activist attacked with acid: “I know I look awful, but Ukraine’s judicial system looks much worse”

- Ukrainian activists protest mounting attacks, Prosecutor General suggests it’s their own fault

- How the Ukrainian government tries to stop its main changemakers