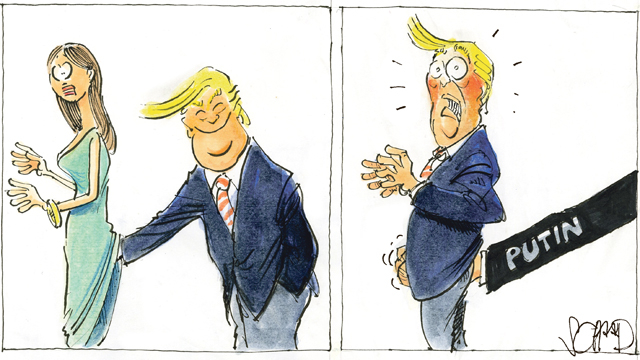

Donald Trump did more than collude with Vladimir Putin in Helsinki. He worked with the Kremlin leader to destroy the three settlements of the 20th century that the United States took the lead in arranging, settlements whose destruction leaves the world and its peoples in a far more dangerous place than it has ever been before.

In the spring of 2014, the current author warned about what was at stake for the US in Putin’s Anschluss of Ukraine in the hopes that the United States would recognize that that Russian action would quickly be recognized as “a new 911 for the US” and the West. Unfortunately, just the reverse has happened.

Below is the text of that article which appeared in The Ambassadors Review. I can only add that at the time, I could not believe that we would sink so low and that future historians will be forced to decide that the real spelling of Helsinki is M-U-N-I-C-H.

Originally published in the Spring 2014 issue of The Ambassadors REVIEW, the foreign affairs journal of the Council of American Ambassadors

In 1991, with the end of the Cold War, the disappearance of the Soviet bloc, and the disintegration of the USSR, many Americans—policymakers among them—believed that we had reached the end of history. They believed that we had entered a new period in which cooperation among countries on the basis of shared commitment to democratic values and free market economics would not only be possible but would become the central feature of the international system.

Ten years later, the Islamist terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11th dispelled much of that optimism but did not dislodge one of the key assumptions of 1991. The 9/11 attacks were the work of sub-state actors not only against the United States but against the international community. Americans and American policymakers continued to assume that the governments of the countries of the world, whatever their differences on a wide variety of issues, had a common interest in working together to defeat such challenges and that the counter-terrorist coalition provided a reliable basis for expanding ties.

Now, 13 years after 9/11, the United States and the international community have been confronted with a challenge that calls that optimistic assumption into question. By occupying and annexing Ukraine’s Crimea by force under the fig leaf of a referendum and by signaling that it views Crimea as a precedent for further action, the Russian Federation, with which Washington had so hoped to establish and develop cooperative ties, has shown itself to be a revisionist, even revanchist power, that is committed not only to overturning the 1991 settlement but that of 1945 as well.

It is tempting to believe that the current crisis is “just about Crimea, which was Russian anyway”—and that isn’t true either, given that Stalin deported the Crimean Tatars from there in 1944, prevented their return, and supported the introduction of ethnic Russians in their place—as all too many in the West are doing. It is critically important to understand just what is at stake and why Russia’s actions in Crimea represent the gravest threat to the rules of the game that the United States has taken the lead in establishing and maintaining since the end of World War II.

There are three reasons for what will seem to many a far too sweeping judgment, reasons that lie in the history of the area and of international decisions and that are to be found as well in the statements of Vladimir Putin and other Russian leaders during the lead up to what can only be described as the Anschluss of Crimea.

First, Putin has violated the basic foundation of the international system by redrawing borders and transferring the territory of one country into another. He and his supporters claim that they are doing no more than the United States did in Yugoslavia, but that is simply false. The United States did not organize the transfer of Kosovo to Albania. Instead, what we are seeing is naked aggression, covered by a trumped up “referendum” and a massive propaganda effort in Russia and the West.

There is one aspect of Putin’s argument, however, that does deserve attention although it is not compelling under the circumstances. As few in the West have been prepared to acknowledge, the borders of the republics in the USSR were drawn by Stalin not to solve ethnic problems but to exacerbate them. In every case, including most famously Karabakh in Azerbaijan but also Crimea and much of eastern Ukraine, Stalin drew the borders so there would always be a local minority nationality whose members would do Moscow’s bidding against the local majority. That had two benefits for the center. On the one hand, it meant that inter-ethnic tensions in the Soviet Union were primarily among non-Russian groups rather than between Russians and non-Russians, a far more explosive mix. And on the other hand, it justified the kind of repressive system that Stalin imposed. Indeed, it meant that the USSR could continue to exist only with such repression. As I wrote in 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev was likely going to discover that a liberal Russia might be possible, but a liberal Soviet Union was a contradiction in terms. When the last Soviet leader liberalized in the hopes of getting that country’s economy to expand, the USSR fell into pieces.

Those borders could have been changed by negotiation. Indeed, as few recognize, republic borders within the USSR had been changed more than 200 times, with land and people being transferred from one republic to another. However, in 1991 and 1992, the United States decided that these lines must not be changed by negotiation or violence. The rest of the world went along with the idea. The reason for that was the fear that the dismemberment of the Russian Federation, a country that is more than a fifth non-Russian, would exacerbate the problem of control of nuclear weapons and could lead to, in Secretary James Baker’s memorable phrase, “a nuclear Yugoslavia.”

For more than 20 years, this view has guided American and Western policy. The most prominent example of this was the insistence that Armenia end its occupation of Azerbaijani lands and return them to Baku’s sovereignty. So far that has not happened. But it is also the case that our decision to accept Stalin’s borders as eternal did not remove the tensions that he introduced as a kind of poison pill should his empire ever come apart. Putin’s move into Ukraine’s Crimea is an indication of just how strong those tensions remain.

Second, and related to this, Vladimir Putin has done something that overturns not just the 1991 but the 1945 settlement as well. He has argued that ethnicity is more important than citizenship, a reversal of the hierarchy that the United Nations is predicated on and a position that has the potential to undermine many members of the international community. While some may see this as nothing more than a commitment to the right of nations to national self-determination, the Kremlin leader’s approach suffers from a fatal flaw, a defect that unless denounced and countered could lead the headfar away about which few in Washington had heard of until very recently, we need to remember the words of the great Russian memoirist Nadezhda Mandelshtam who wrote that “happy is the country in which the despicable will at least be despised,” even if at any one point there may not be anything more than one can do.

Putin’s occupation of Ukraine is a second 9/11, a warning that the optimism of 1991 was misplaced and that the kind of cooperative future we hoped for has been put on hold for some time. That future is still possible. There are many Russians and others who want it. Unfortunately, Vladimir Putin has demonstrated that he is not among their number unless we are prepared to concede to everything he wants.

Read More:

- Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact revisited, Part 1: The interwar prelude

- Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact revisited, Part 2: Hitler’s Anschluss

- Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact revisited, Part 3: The way to European catastrophe

- The greatest danger in Helsinki: new ‘secret protocols’ or simply ‘understandings’

- Trump’s challenging of broad consensus on Crimea will lead to a broader war, Skobov says

- Putin and Trump aren’t conservatives: they’re reactionaries, Golts says

- Trump’s best friends

- Trump’s summit with Putin constitutes an ‘unprecedented act of betrayal,’ Eidman says

- Trump’s statement on Crimea can lead to serious consequences, says American analyst

- Putin-Trump meeting won’t result in dramatic changes on Ukraine many fear and some hope, Shevtsova says

- ‘As long as Trump’s in the White House, Putin will remain in the Kremlin,’ Nemets says

- Trump may negotiate with Putin for the same reasons he’s talking with Kim Jong-Un, Novoye Voennoye Obozreniye suggests

- West less afraid of a new Munich than of Kremlin collapse, Shevtsova says