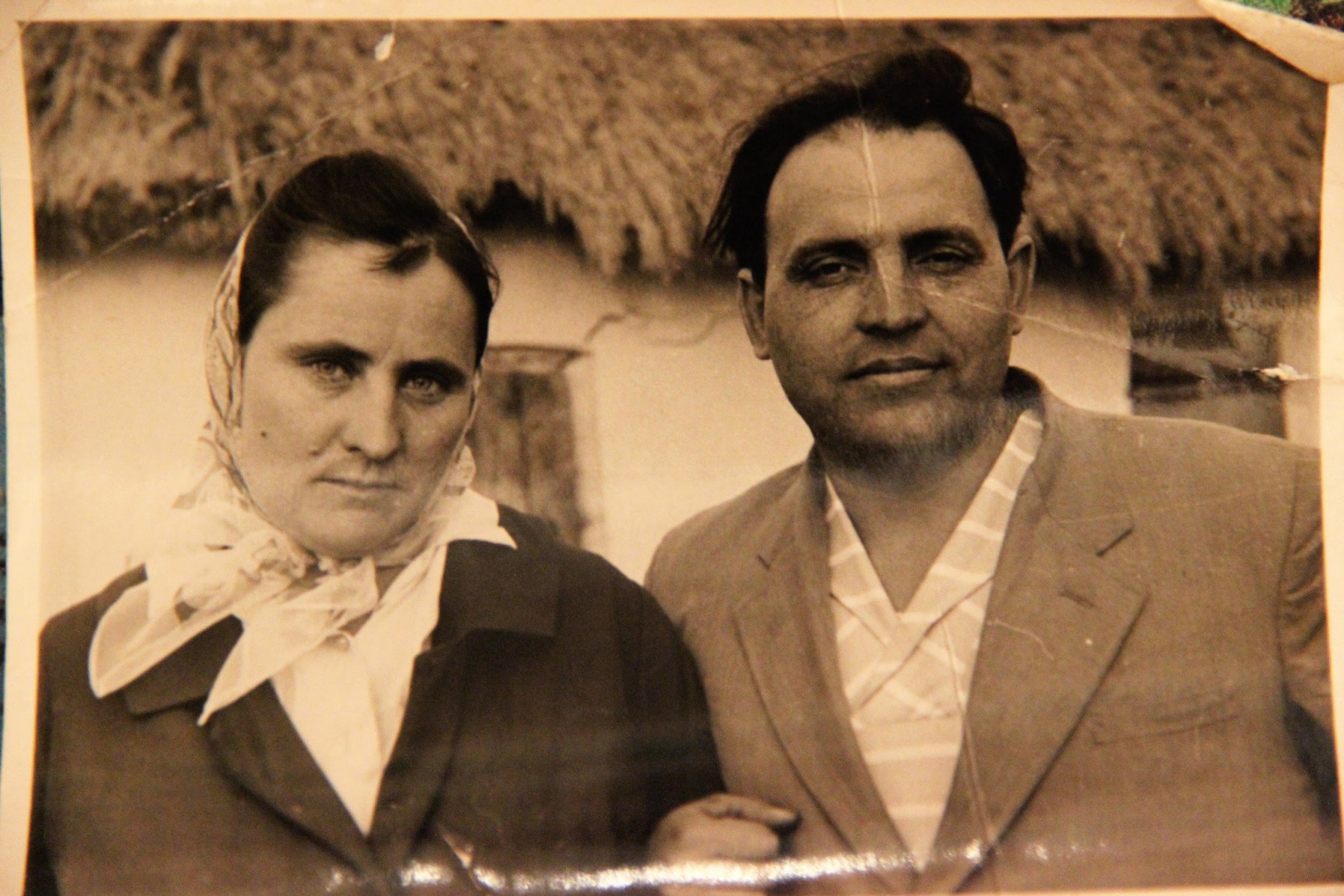

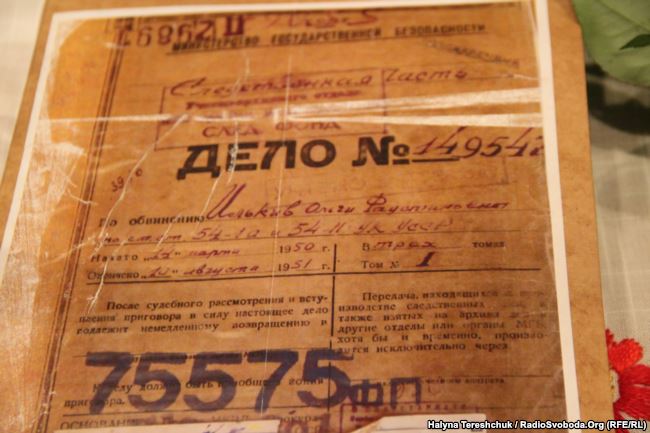

97-year-old Olha Ilkiv, accompanied by her son Volodymyr, arrived at the SBU headquarters in Lviv to pick up three volumes of copies of her criminal case. Olha was arrested by the NKVD in 1950 and incarcerated in the Prison on Lontskoho.

“This is a clear victory over the man who beat me and tortured me. His name was Lavrenko. He was a butcher who forced me to swallow psychotropic substances that aren’t allowed anywhere… even in prisons. Maybe that’s why I’m partially blind. There were no breaks from this routine; there wasn’t even time to eat the meager rations that we were given. They brought us into a room, then took us out, but we were constantly observed through a little hole in the door. Yes, I suffered a lot, but I didn’t commit suicide, and that’s very important. I think someone somewhere was praying for me…. Lavrenko told me that I would never see my children again; they’d been taken away. And even if I found them, they’d probably spit in my face…. Yes, that’s what he told me. I replied that I’d go from house to house, from village to village, until I found them.”

When Olha worked as liason officer to UPA commander Roman Shukhevych, she kept her son and daughter safely hidden. She was arrested in 1950 and sent to the Prison on Lontskoho in Lviv. Her children were taken away and placed in an orphanage by the Soviet authorities. Their surname was changed to Boyko. Olga Ilkiv was incarcerated for 25 years. During her imprisonment, she never betrayed her comrades. Her interrogators told her where her children had been sent, and she began searching for them as soon as she was released. Olha remembers that at first her son and daughter were hostile, because Soviet propaganda had brainwashed them, telling them that the OUN and UPA were criminal organizations.

“They’ve always tried to steal everything from us, but we’ve always survived… This is our destiny. We have a big country and rich productive soil, but we’ve always been surrounded by enemies.” remarks Olha Ilkiv.

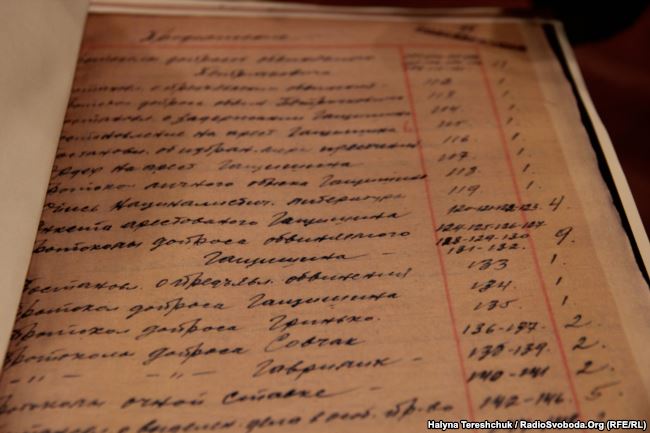

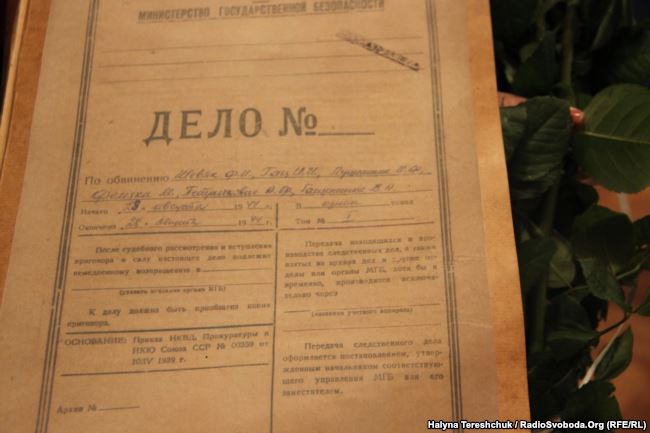

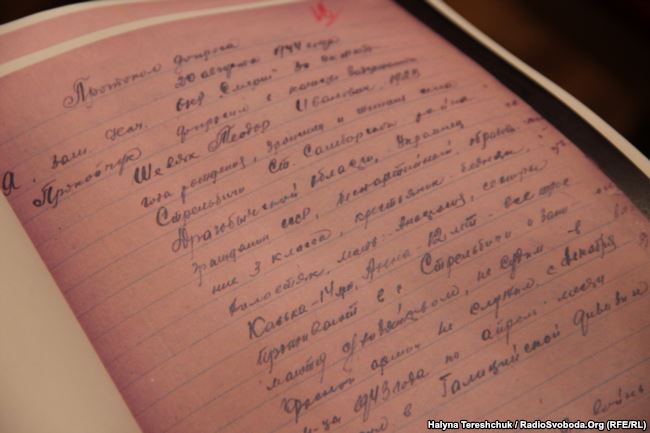

Biographies written by the NKVD

The criminal case against Anastasiya Zakydalska is recorded in one volume, a copy of which was transmitted to her daughter Nataliya. Anastasiya is 94 years old and has difficulty moving around and travelling. She was arrested in August 1944 and charged with working for the UPA. She was labeled as “a member of the OUN-UPA gang”.

“My mother was a nurse and liaison officer. She was incarcerated in Drohobych prison and treated like a common criminal. She was a pretty young girl with long braided hair. She spent 25 years in exile, mostly in Inta, Komi Republic She returned to her home in Boryslav, Ukraine in 1983. Despite the fact that Russian was spoken everywhere and we were in an aggressive Russian-speaking environment, our parents taught us Ukrainian, as well as Ukrainian history and traditions.” says Nataliya Zakydalska.

When Olha Ilkiv was asked whether she’d let her son read the criminal report, she replied:

“What do you think those bastards wrote about us? They reported whatever they wanted, but definitely not what we said ...”

However, for historians studying the twentieth century, including OUN and UPA activities, it is very important that these two women and other survivors compare existing records and historical documents. Historian Mykhailo Romanyuk, who has studied the archival documents of the SBU General Directorate in Lviv Oblast, underlines that all criminal cases stored in the archives are important as they are part of family histories that help scholars understand the Ukrainian national liberation movement.

“These cases should be verified with other documents. We’re trying to find and compare three sources: criminal cases stored in archives, documents drawn up by the occupation authorities, and partisan documents and memoirs. They’re important to all concerned families as they’ll be able to evaluate and compare all the materials. The criminal case against Olha Ilkiv provides us with a lot of biographical material… where she lived and studied, her activities in the ranks of the resistance movement, etc.” explains Mykhailo Romanyuk.

60,000 archive materials related to the activities of the Soviet regime in the 20th century are listed in the SBU archives in Lviv Oblast. These are people, who, like Olha Ilkiv and Anastasiya Zakydalska, were rehabilitated in 1991. However, there are more than 8,000 cases concerning people who have yet to be rehabilitated by Ukraine.

“More and more rehabilitation processes are gradually beginning in Ukraine. The SBU will also be an active participant in the process of reviewing cases involving UPA soldiers, who, for one reason or another, have not been included in the lists of rehabilitated persons. Today, we’ve symbolically handed over two cases. We want to dispel the myths created by the Soviet regime and supported by the current Kremlin regime so that Ukrainians will finally know the truth about what took place in Ukraine. It’s important to understand history so that the same mistakes and tragic events will never happen again.” says

In the 1940s and 1950s, when Olha Ilkiv, Anastasiya Zakydalska, and other UPA activists, young and dedicated women, were arrested and tortured, no one could imagine that in a few decades they would receive a copy of their interrogations. These reports reflect the stories of their lives, but “written by the enemy’s hand” and rather far from the truth, according to both women.

“We did not give in then, and we will never give in!” concludes Olha Ilkiv.