As a hundred years of eyewitness-participant accounts and later historians’ scholarship have long affirmed, the Revolutions of 1917 have been correctly understood as having been about the politics of war and peace and—inextricably linked with the growing costs of the world war—social justice appeals for peasants and workers, as well as a broader access of all citizens to self-government by way of a thoroughgoing democratization of all imperial institutions.

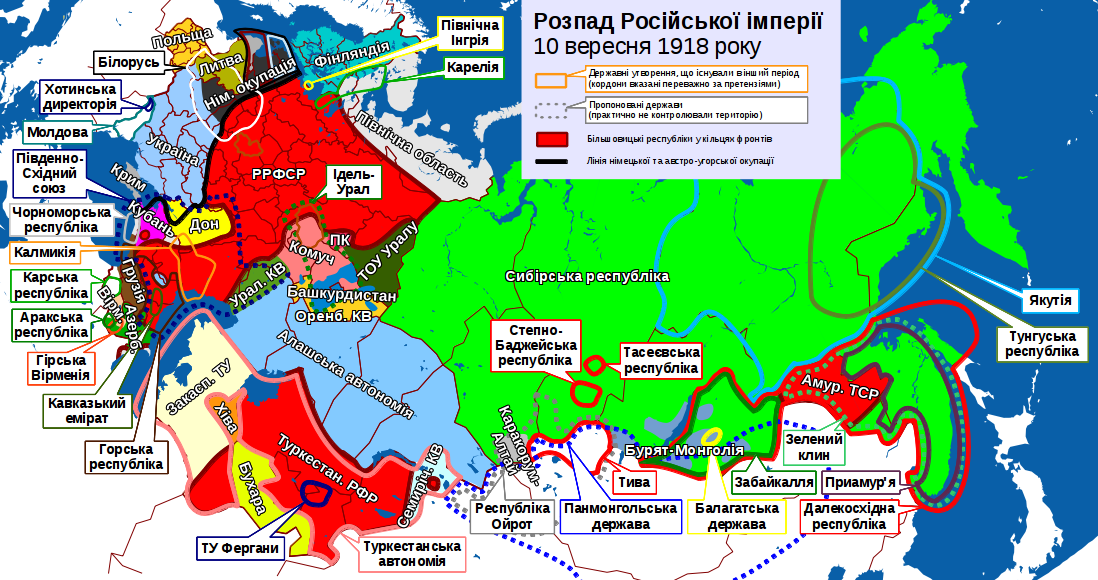

But outside the capitals of Petrograd and Moscow, and even for large non-Russian communities in those capitals as well, the revolutions of February and October 1917 were also about empire and national self-determination in one form or another.

The growing calls over the months of 1917 for a federal and democratic republic with equal rights for non-Russians (with Russians) in such a republic also linked any solution of the war or any progress toward social justice to the “national question,” or, alternately, the question of the future of the empire.

In most imperial borderlands, national self-determination might also be understood as national territorial autonomy.

The Provisional Government [of Russia - ed] almost immediately after its formation lifted nearly all censorship of press and public speech, making revolutionary Russia arguably the freest country in the world for a few months between February and October (O.S.). The Provisional Government also abolished many of the policies of legal and administrative discrimination of the non-Russian and non-Orthodox citizens of revolutionary Russia and allowed the return of political exiles and prisoners, including those persecuted for agitation for federalism and national rights. But those measures failed to address the larger issues of the roles of non-Russian citizens in their own self-government, above all the demand for recognition of the principle of national autonomy.

The most ardent and experienced “national” opponents of the autocracy and, specifically imperial rule, had been the Poles, with their large west European émigré communities and their histories of legal and clandestine resistance. But because Poland was under German occupation throughout 1917, the largest movements for national self-determination were the Ukrainian and Finnish ones, but the Ukrainian revolution was perceived as the greatest threat in Petrograd.

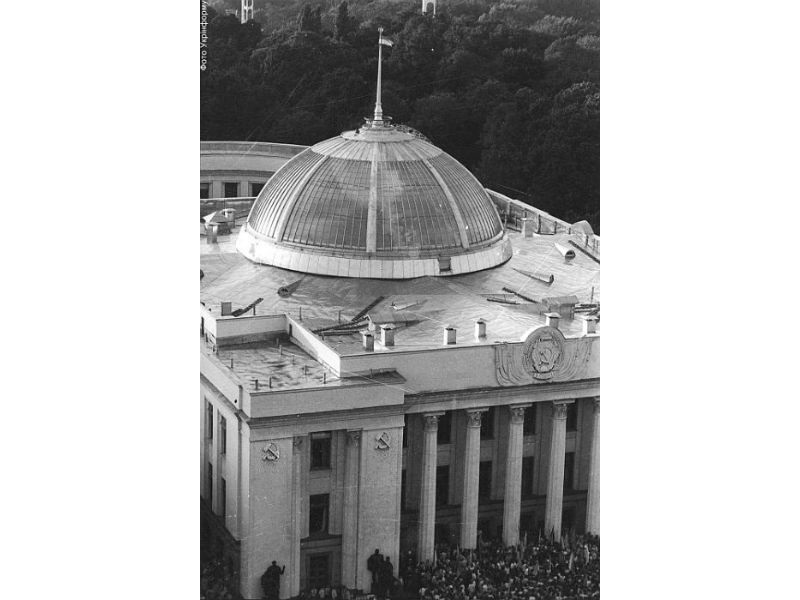

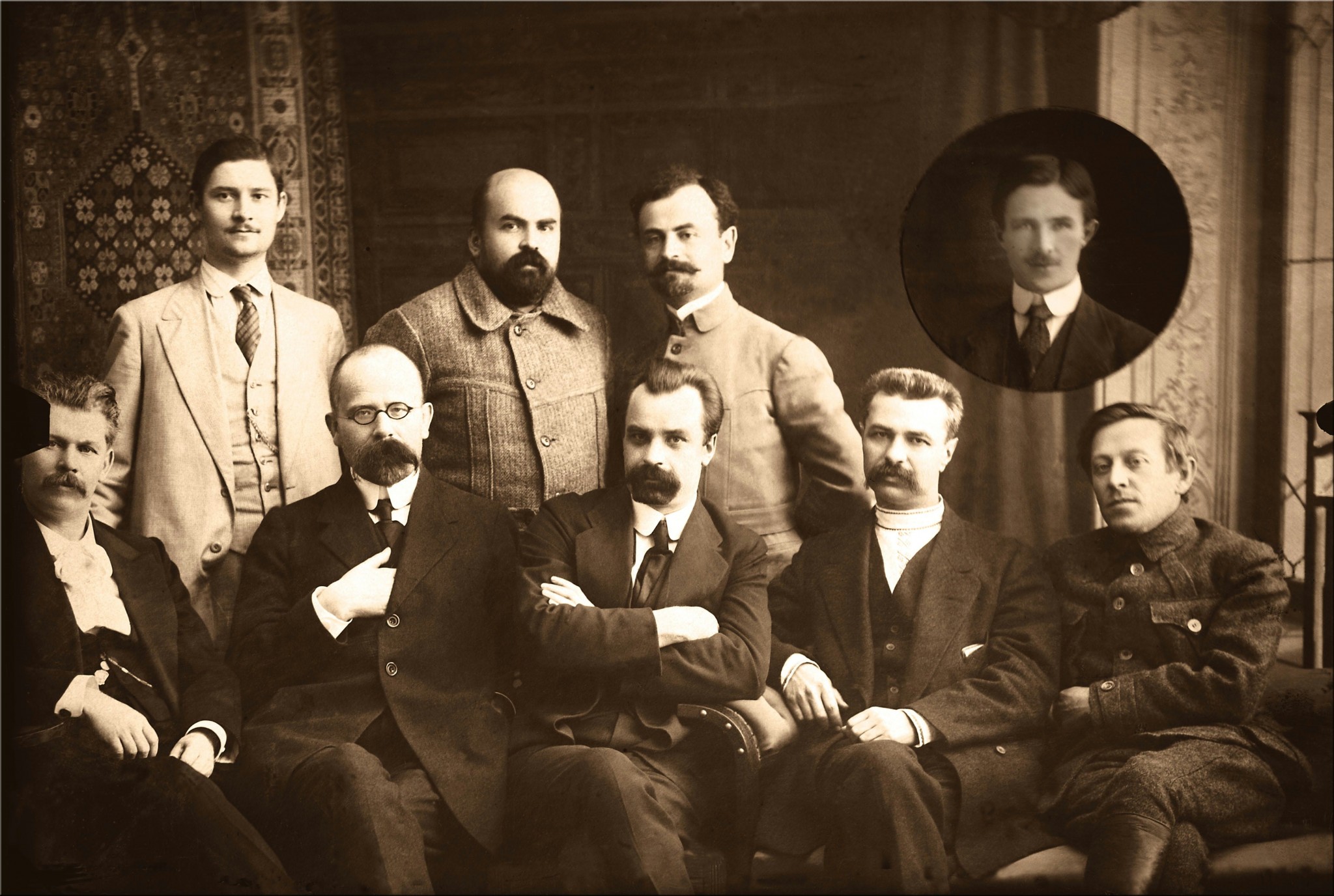

In Kyiv the Ukrainian Central Rada that was created by a group of veteran Ukrainian activists in the Society of Ukrainian Progressists (TUP), but quickly found mass support in the Ukrainian soldiers’ movement, peasant congresses and the rapid growth of “Ukrainian” parties—above all the Party of Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionaries and the Ukrainian Social Democrats--that also quickly began to distance themselves from their all-Russian counterparts.

Indeed, virtually from day one, the revolutions in Petrograd and Kyiv began to diverge from each other, but other national liberation movements took advantage of the Ukrainian movement’s advocacy for a federalist and democratic Russian republic and often worked in solidarity with the Ukrainian movement, above all the Jewish socialist parties in Ukraine, the United Zionist Labor Party, and the Poalei Tsion. At first, even local Russian Kadets and other

At first, even local Russian Kadets and other democratic all-Russian parties in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other cities claimed by the Ukrainian movement were far more willing to collaborate in a coalition civic organizations than were their counterparts in the capital city, Petrograd. This was even true for Moscow politics, but most developed in the historic “borderlands” of the empire.

The Ukrainian Central Rada convened the first and only Congress of oppressed peoples of the Russian Empire in Kyiv in September 1917.

The Ukrainian People’s Republic that was proclaimed in the Fourth Universal of the Central Rada in January 1918, also promulgated the first law of personal national-cultural autonomy that was the joint work of a Ukrainian Socialist Federalist, Oleksander Shulhyn, and Farainigte leader Moishe Zilberfarb. This law was inspired by the Austro-Marxist reform programs of Karl Renner and Otto Bauer and was transmitted to the Russian empire via the Jewish Bund, which had its greatest membership in the western borderlands that bore the “footprint” of the early modern Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The only similar contemporaneous experiment in national autonomy was adopted in Lithuania in the early 1920s, but abandoned by the end of the decade. Poland was obliged to undertake the protection of its minorities as a condition of its 1919 treaty signed as part of the Versailles peace talks. The Bolshevik Council of People’s Commissars created a People’s Commissariat of Nationality Affairs, headed initially by Joseph Stalin, but the Commissariat was not motivated by the protection of the rights of minorities as much as it was an effort to win over the large populations of prisoners-of-war and refugees, including Poles, Jews, and others from the influence of “bourgeois” nationalist parties and organizations.

The Ukrainian Central Rada, by contrast, formed a General Secretariat for Nationality Affairs, with three initial sub-secretariats for Jewish, Polish, and Russian affairs. This arrangement was upgraded in January 1918 to a ministry with the proclamation of the Ukrainian People’s Republic and the Fourth Universal, which itself was published in four languages: Ukrainian, Yiddish, Polish, and Russian.

Though the Ministry went into abeyance under the rule of Hetman Skoropadskyi, it was revived with the return of the Ukrainian socialist government in the Directory at the end of 1919. Among other tasks, the Ministry for Jewish Affairs fought against the anti-Jewish pogroms committed by Ukrainian troops under Symon Petliura, but Jewish ministers remained in the Ukrainian governments and were also numerous among their diplomatic representatives.

The West Ukrainian People’s Republic was probably even closer to the post-1918 outcomes of revolution in its broad acceptance of parliamentary democracy and a multiparty system. The Bolshevik revolution and its rapid evolution toward single-party dictatorship quite consciously repudiated the Central European Social-Democratic outcome of the revolution, but the Ukrainian revolutions, both in Kyiv and in Lviv, aspired to the more western alternative.

In this sense, the Ukrainian revolution bears comparison with other “third-way” Russian democratic regimes, most notably in Omsk, Samara, Ufa, where coalitions of “democratic parties” included left Kadets and, usually at first even Bolsheviks, but eventually stood for all-socialist coalition governments.

The Ukrainian revolution also proclaimed the principle of all-socialist homogeneous government, a slogan also articulated in Petrograd before October 1917, but also acted on that aspiration in the composition of the Ukrainian Central Rada and later the General Secretariat, and still later in the Ukrainian People’s Republic and its Council of Ministers.

Finally, on the issues of war and peace, the Central Powers in effect signed two treaties that were both the first to halt fighting in the War, one with Ukraine on 9 February 1918, and a second with Soviet Russia a month later.

At first, the Soviet Russian delegation recognized the Ukrainian delegation in the hopes of having an ally against the Germans and their Central Power allies in Brest-Litovsk. But shortly after that recognition, the Council of People’s Commissars declared war on the Ukrainian Central Rada and proclaimed its own Ukrainian Soviet Republic in Kharkiv following a soldier-worker dominated congress of soviets there.

When the Germans refused to accede to Trotsky’s demands that the Ukrainian People’s Republic delegation no longer be recognized in favor of the Kharkiv “Ukrainians,” the first peace of the war, at least in words and principles, was a just one that recognized Ukraine’s sovereignty. The second treaty with Soviet Russia, following a German offensive that brought the Soviet delegation back to Brest after a split in the Central Committee which had had to move in the meantime to Moscow, was indeed a draconian one, a victor’s brutal peace of submission.

The peace with Ukraine, however, turned quickly into a brutal occupation of the country once the Germans had restored the Ukrainian People’s Republic. Also in short order, the German occupiers tired of the socialist People’s Republic and abetted the coup by the former tsarist general Pavlo Skoropadskyi.

In this brief survey of some of the key moments of the Ukrainian revolution, I have tried to highlight that very quickly the Ukrainian revolution diverged from the Russian ones, especially in Petrograd, but that it shared more with various Russian “third ways” (between Red and White dictatorship) and perhaps more still with the politics of revolution in November 1918 in central and eastern Europe.

As former Ukrainian president Leonid Kuchma titled his book, Ukraine is not Russia; similarly, the Ukrainian revolution is not the Russian revolution, despite its inextricable and fatal links to that revolution. It is also closer to the other revolutions of non-Russians in the empire, from Jews to Tatars to Caucasians to Poles.

We have long acknowledged and taught that 1917 was not one, but many revolutions, including parallel, sometimes overlapping but often conflicting movements of soldiers, workers, peasants, white-collar workers and other intelligentsia and social groups. But all these revolutions were refracted through national, imperial and colonial prisms, so there were also Ukrainian, Polish, Jewish, and Tatar revolutions, something Richard Pipes described long before the “imperial turn” in his Formation of the Soviet Union.

Read also:

- Illusion of a friendly empire: Russia, the West, and Ukraine’s independence a century ago

- Ukraine remembers 100 years of revolution