The topic of de-occupying Donbas has become more popular among Ukrainian authorities, giving hope that after nearly three years of a quagmire war, words will soon start turning into reality.

At present, 2.5% of continental Ukraine is uncontrolled by the Ukrainian government, having in 2014 become part of the unrecognized Russian satellite states, the Luhansk and Donetsk “People’s Republics” (with illegally annexed Crimea, the total Ukrainian area occupied by Russia rises to 7%). The Minsk peace process has so far been ineffective to stop the conflict between the Ukrainian army and combined Russian-militant forces in Donbas and get the territory back under the control of the Ukrainian government.

But it’s important to remember that not only land and infrastructure should be returned. The main fight should take place for the minds of people of Donbas who allowed themselves to be misguided by stereotypes and falsifications to the extent of destroying their lives. Nowadays, different initiatives focused on cultural exchanges for Ukrainians from different regions started to appear. They are called to repair what stereotypes had destroyed.

Let’s take a look which stereotypes existed (and often still exist) among the citizens of the eastern Ukraine towards the other regions of Ukraine.

Destroying myths

The radical nationalists. In the very heart of Lviv, on the back streets near the central square somewhere in a basement the Kryivka restaurant lies in wait. One would not find it that easily. A visitor should say the right password to the host when he says “Glory to Ukraine!” And the right answer for it is “Glory to the heroes! [Heroyam Slava!].” Inside, the restaurant is equipped as a bunker of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. The dishes are also titled correspondingly.

The restaurant gathered the quintessence of the myths that Russians and eastern Ukraine citizens believe about the dwellers of western Ukraine – that they are national radicals worshiping Stepan Bandera, the main ideologist of Ukraine's nationalist movement, and who can beat you up for speaking Russian. The daring decision of the restaurant was successful – the myth about Lviv nationalism was successfully monetized. Before the war in eastern Ukraine had started, any Lviv citizen would tell you that all this entourage attracted mostly tourists from Russia and eastern Ukraine. They wanted nationalism and they received it, but also on the streets of Lviv they could have debunk all the stereotypes by themselves observing the friendly atmosphere of the city. But what about those who hadn’t visited Lviv themselves?

While alleged radical Bandera followers became a topic for jokes in western Ukraine and around the capital, in eastern Ukraine they are still perceived as a legitimate reason for fear. During Euromaidan, Russian and pro-Russian TV succeeded in scaremongering many people living in Crimea and Donbas with an alleged strong Bandera movement and radical nationalist movement in Ukraine. In Russia, the whole current Ukrainian government was (and often still is) depicted as a group of radicals who seized state power, in an attempt to safeguard the Russian population against attempting a public uprising. So sometimes even pro-Ukrainian people in the east of the country believe that after Euromaidan Revolution, fascists and radicals seized power in Ukraine.

Donbas is feeding all Ukraine. The stereotype that the hard-working Donbas is generating excessive income and subsidizing the rest of Ukraine is one that its residents like to believe themselves. However, the facts are that in 2013 Donbas received twice more from the state budget than it gave.

The funny thing is that it potentially could have been true. Donbas, which includes the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, is an industrial area with the largest enterprises and factories in Ukraine and a significant concentration of natural resources, including coal, rock salt, dolomite, limestone etc. However, all the wealth of it did not go to ordinary people. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the privatization processes of the period of “wild capitalism” led to the enterprises being taken over by people who were standing with one leg in the local power structures and had the other in the criminal world. The factories started to decay, and the majority of owners had no plans to develop them.

The myth that Donbas feeding the rest of Ukraine became especially popular during the period when ousted President Viktor Yanukovych and his Party of Regions were in power. Yanukovych, himself a native of Donbas, exploited the myth in the media he controlled quite successfully and rode upon the feelings of rage of the residents of the industrialized region, while he and his entourage robbed Donbas as well as the whole Ukraine.

The most popular TV channels in Donbas constantly praised the “good actions” of the authorities while creating enemies out of representatives of other regions were created. Mostly it was a vague “Kyiv” which was only entertaining itself while Donbas was working ard to feed them. And if somebody asked why Donbas was poor, it was first of all Kyiv and then the other Ukrainian regions which had taken what Donbas laboriously produced.

This myth was especially exploited during the Euromaidan Revolution, epitomized in the phrase “while Donbas was hard at work, Kyiv entertained itself by jumping on its streets [meaning protesting],” further fueling the opposition of the residents of eastern Ukraine to the pro-democratic protests in the capital.

Stereotypes created by isolation. Sociological data published by the Tyzhden magazine in 2012 revealed that not only had the majority of Ukrainians (77%) never traveled abroad, but many (36%) haven't even traveled outside of their region.

There can be different reasons for this, like the lack of money or time, and no necessity to travel. An important detail is also that the transport system of Ukraine is not adapted for traveling between different parts of Ukraine. The transport infrastructure of Ukraine had been built during the time of the Soviet Union, when the main goal was connecting a socialist republic with its Soviet center, Moscow, not connecting different parts of the republic between themselves. Unfortunately, the situation persists until today. For example, a train ride between south-Ukrainian Mariupol and western Ukrainian center of Lviv, which have 1000 km in between them, takes 24 hours. Also, there is no direct railway connection between the major sea resort of Odesa and Lviv, which are separated by 630 km!

Media also played an important role in the isolation of Donbas, especially the nationwide channels TRK Ukrayina and Inter. The first is owned by the richest oligarch of Ukraine Rinat Akhmetov, the second used to be controlled by pro-Yanukovych forces and even had a share of the Russian capital. Now the channel is used by the Opposition Bloc, successor to the Yanukovych’s Party of Regions.

Nevertheless, more or less united

Still, even in 2012, according to the above-mentioned research, only 12% of respondents considered the relationships between Ukrainian macro regions as strained. 80% expressed keen dissatisfaction at the discriminative statements of politicians towards different regions of Ukraine. Those who considered the relationships between regions to be strained thought that the regions can be united if everyone will have decent living standards (43%) and industry and agriculture will recover (25.8%). And 21.8% thought that a common history can be unifying.

The de-occupation strategy of Donbas has to envision how to dispel stereotypes and provide better living conditions for people from different Ukrainian regions, so there would be no temptations of creating fake republics. If tackling the second task is mostly up to the government, the first one started to be implemented by volunteers.

The war in eastern Ukraine became a catalyst for developing the solutions aimed to glue together what was broken. It were volunteers who intuitively recognized that real communication is a powerful instrument for unification. They direct their initiatives mostly at the youth, the active part of the population which in a few years will be the main force for building the country.

Exchange programs seeking to unite Ukrainians

The New Donbas initiative appeared in Autumn 2014 when the warfare in the east was in a full play. The volunteers from Kyiv came to a damaged school in a town Mykolayivka in Donetsk Oblast which experienced the occupation by the so-called “Donetsk People's Republic” and then was liberated by the Ukrainian army. The idea of the initiative was to communicate with students through different creative workshops. In parallel, the school was physically renovated. The volunteers agreed not to talk about politics with local people. However, hot topics were still raised in the process. First, the volunteers were treated with suspicion, mostly because all of them took part in Euromaidan Revolution which was perceived as a gathering of radical Bandera followers. However, in the process of communication, both sides realized that they perceived each other mostly through the prism of media. In fact, they had the same problems, the same challenges, and the same values. After this successful experience, many other creative projects were launched in Mykolayivka.

Nowadays, there are several creative initiatives supporting youth exchanges from different regions. Euromaidan Press collected some of them.

The Ukrainian Leadership Academy was founded in 2015. The Academy foresees a 10-month long program for students from all over Ukraine. It's based on an Israeli model when students live and study in the academy 6 days a week and combines physical, academic, and spiritual education. Its guest lecturers include politicians, civil activists, and other people whose role is important for Ukraine. Also, it envisions a lot of traveling across Ukraine and abroad. Its goal is to gather young people with a high leadership potential and give them instruments for development, as well as help them to find their further path in life. The education, living, food, and travels are covered by the Academy, the participants should only pay the registration fee. It has centers in Kyiv, Lviv, Poltava, Mykolayiv, and Kharkiv.

“It was the best year of my life, a crucial point which changed the direction of my life. First, because the Academy includes 10 months of living with people from all over Ukraine. My group consisted of 39 students, plus 6 mentors from each region of Ukraine. And when you live with people for ten months, you start to realize each others’ education and world view, and that helps you identify with one another. You have the opportunity to look at the traditions of different oblasts.

We traveled a lot across Ukraine. Not as tourists. Exploring was our main task; we were researchers,” says Valeria Rakytianska one of the first alumni of the Academy.

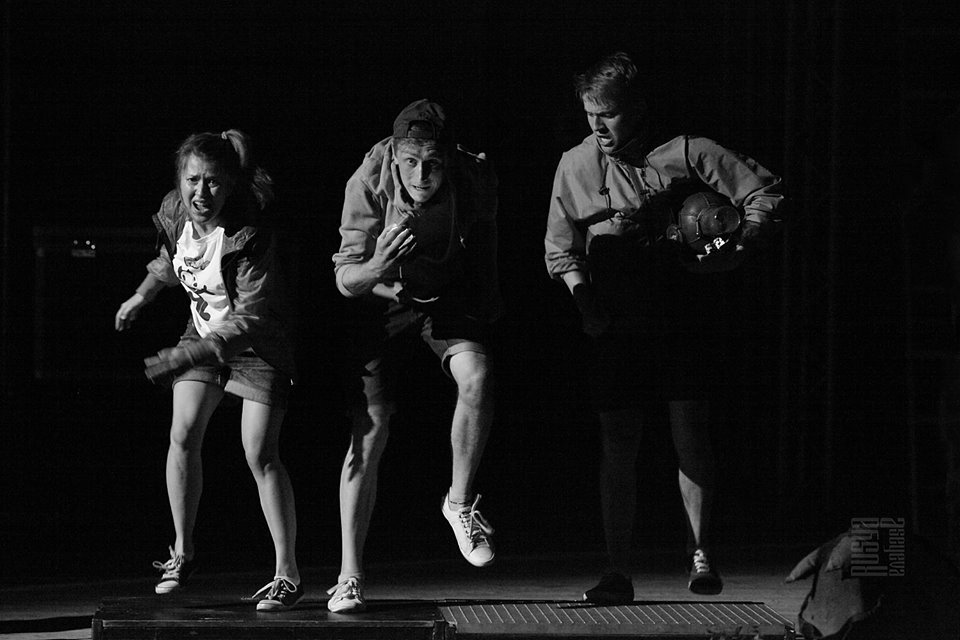

Class-Act: East-West is a theater project which takes place in Kyiv for the second year in a row. It gathers teenagers from eastern and western Ukraine. Here, with the help of professionals, they learn the basics of acting and drama and learn how to write plays by themselves for 10 days. Afterward, their plays are performed by famous Ukrainian actors.

This year the participants are teens from the front line city Shchastia in Luhansk Oblast and students from the city of Klesiv in Rivne Oblast, where illegal amber extraction became the cause for local turf wars.

“Many Ukrainian teenagers are united by the way how and where they spend their time – in abandoned zones, quarries, cemeteries and other not very pleasant but mysterious places related to some danger,” explains Natalka Vorozhbyt, the curator of the project.

She says that the stereotypes about the east and the west which were put into the kids' minds by their parents crumble immediately when the teenagers come to Kyiv.

She also emphasizes that the project gives an opportunity for the kids to chose a creative profession – an actor or a playwright in the future:

“They think that it is impossible. But I want for creative kids to get involved in theater and cinema and improve the general situation in the field. Fresh blood is needed, as are people with experience, people who know another life. They are our sources of information. Considering what is going on in both regions, these teenagers have what to say.”

The list of famous actors taking part in the project is impressive – the teenagers know the majority of them from TV series and films. Last year even the Minister of Culture Yevhen Nischuk, who is also a professional actor, took part.

“It is very symbolically that this project connects the east and west. I am happy that we could do it. The energy of creativity is very strong. As soon as we start creating in this country, everything will be wonderful. Starting from the children, and going to adults and others. Create new plays, new pictures, new works, new working places, new perspectives, development, look into the future. We should show that this is possible,” said Andriy Sharaskin, a cyborg (Ukrainian soldier who defended the Donetsk Airport from Russian-militant attacks) and famous director who was working with one of the plays written by children.

The “Truhanivska Sich” trains of unity and reconciliation. These trains gather youth, kids, students, activists, and soldiers from different regions of Ukraine and take them on a journey across different Ukrainian regions, so the passengers get acquainted with life and traditions of different cities. For many passengers, this was the first trip so far away from home. So far, there have been five such trains.

“'Everybody in the east is a separatist, everybody was calling for Putin to bring in the troops [ironiy].' But we were not perceived like that, at I had not felt it. We should bring goodness, show people that we are all the same. We just should hold each others’ hands and understand that we are united,” says project participant Nina Surmova, a student from Donetsk who now lives in Sloviansk, Donetsk Oblast.

“People from the east say that we are Bandera followers, that we hide tanks under haystacks. But it’s not true. We want to show that there are essentially no differences between us,” says Tetiana Parashchuk, Nina’s peer from Lviv.

Zminymo Ukrayinu Razom [We’ll Change Ukraine Together] is a pedagogical project for the exchange of teachers from eastern and western Ukraine. The project participants are teachers from Luhansk, Lviv, and Ternopil oblasts. In 2017, 50 professionals from near the frontline Luhansk Oblast went for about 2 weeks to work in western Ukraine. Last year the Luhansk Oblast teachers worked with students from western Ukraine for about a month. The professionals from western Ukraine in their turn came to Luhansk Oblast.

“When I was offered to go to the Lviv Oblast, I immediately agreed. This is a huge experience, getting acquainted with new people, communicating. I will go to a local lyceum in the Yavoriv district. I want to see how other teachers are taught. There were absolutely no fears before the trip because it’s all our Motherland,” said Oleksiy Honchar an English teacher from Luhansk Oblast, a participant of the program.

Ukraine is the big country with a population of 45.2 mn people [as of 2015] and the area 603,628 square kilometers (7% of which is uncontrolled by the Ukrainian government - occupied Crimea and the territory under the Luhansk and Donetsk “People’s Republics). While there are indeed many differences between the inhabitants of its different regions, these exchanges are helping Ukrainians see that they have much more in common.