Natalya Zubarevich, perhaps Russia’s most prominent specialist on developments in the regions beyond the Moscow Ring Road, says that today “there are no places where the situation is “especially critical” because as the wave of protests shows, it has become “critical” everywhere from Vladivostok to Kaliningrad.

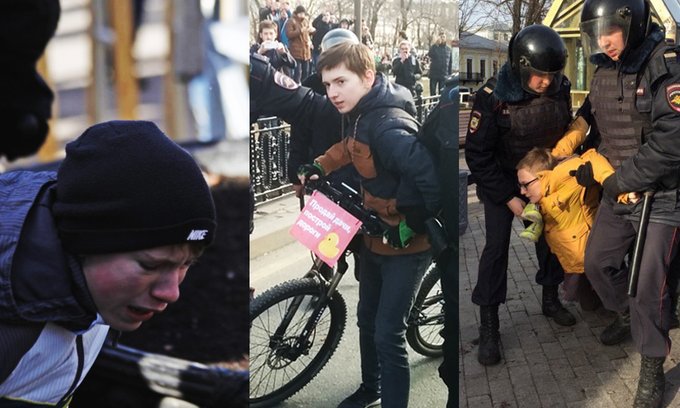

As is almost invariably the case, most Russian and Western reportage has focused on Sunday’s demonstrations in Moscow and St. Petersburg. But what makes the current wave of protests new and important, the director of the Independent Institute for Social Policy says, is that protests took place across the country.

Zubarevich argues that the protests outside of Moscow and St. Petersburg are important not only because they show the extent to which the arguments opposition figures are making in the capitals resonate but also because they underscore the entrance into political activity of new and sometimes very different forces, a trend that challenges officials at all levels.

“Both Novosibirsk and Yekaterinburg, where many people participated in the protests, are macro-regional centers with a modernized population that wants the authorities to take their interests into account,” the regional specialist says. They have always been leaders in such protests.

But the situation in Makhachkala, the capital of Daghestan in the North Caucasus, is very different. Although it has nearly a million residents if one counts its suburbs, Makhachkala is hardly “a major macro-regional center” or a place with a long history of participating in Moscow-led protests.

“The special quality of that city is many interest groups operate there,” including ethnic and religious ones; but they share one thing in common with other Sunday demonstrators: “Over the last several years, with the arrival of Ramazan Abdulatipov, dialogue between the powers and the population has collapsed,” with the former preferring to use force to settle all issues.

Consequently, Zubarevich continues, “if Novosibirsk and Yekaterinburg are simply advanced centers which follow Moscow and Petersburg, Makhachkala is a painful point where alternative points of view have been maintained, and the level of pressure is higher than the average elsewhere in Russia.”

Two other cities at opposite ends of the Russian Federation – Vladivostok and Kaliningrad – highlight other aspects of these phenomena. In Vladivostok, the specialist says, people have greater contact with the outside world and are thus more inclined to develop critical views about the regime.

Kaliningrad, which one might have expected to display a similar trend, hasn’t, Zubarevich says. There, people didn’t protest; and that pattern allows for the following conclusion: “Participation in protests in Vladivostok is good news, but non-participation in Kaliningrad is bad.”

“It is possible,” she says, “that the passivity of the Kaliningraders is connected with the fact that in 2011-2012, they took an active part in protests” and then the authorities responded in a better way: they paid more attention to local needs, they maintained a dialogue, and that reduced political activism by the population.

According to Zubareivch, this is not a reflection of “the good work of Navalny.” In many places, such as Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, he and his supporters not that popular. Simply the process has matured, and the time has come. People have told the powers that be: ‘it isn’t necessary to live on Mars.’”

The current crisis began in 2013 and has only gained speed and size, more slowly where the authorities have responded with dialogue and more rapidly where they haven’t. (For an example of this, see how Kazan’s ban on protests there backfired and made the situation even more tense.)

But now, Zubarevich says, no one can avoid concluding that “this is a federal problem: the participation of local officials only slows the decline in some places but more commonly accelerates it.” And that crates “a very interesting situation: it is impossible to localize the problems: they are everywhere.”

Moreover, as Sunday’s numerous demonstrations outside of Moscow show, “in regional centers this crisis is felt no less than on the periphery. This too distinguishes the current crisis from all preceding ones.”

Zubarevich does not discuss this, but geography also helped the Navalny protests in another way: The successful demonstrations in the Russian Far East hours before they were to begin in Moscow encouraged people in the capitals to come out, something that will only intensify if there are more such demos in the future.

Related:

- Why aren't Russians protesting against Putin?

- Eurovision, Russia, and weaponized disability

- 'Putin is the Bin Laden of today' and other neglected Russian stories

- Day in History, 2014: UN rejects Russia's violent attempt to reshape borders

- US sanctions on Russia effective, don't hurt American economy, report finds

- New Threats Require a New Response: What the Baltic Countries and the US Face in Putin's Russia

- Gerard Depardieu, the Eurovision contestant, and other Russian artists Ukraine banned

- Former Russian MP Voronenkov, key witness in Yanukovych treason case, assassinated in central Kyiv