Even though Moscow officials feel perfectly free to talk about ethnic Russian communities in other countries and the need to bring them under Russia’s umbrella one way or another, Moscow politicians and commentators are outraged that a Ukrainian official says Kyiv has a legitimate interest in Ukrainian communities inside the borders of Russia.

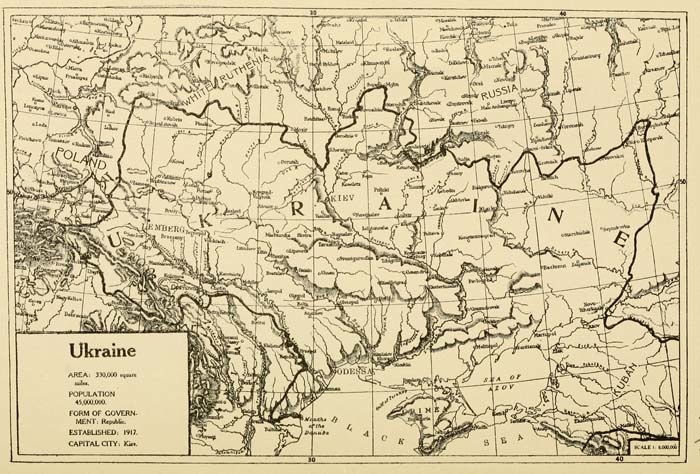

Last week, Pavlo Zhebrivskiy, the head of Ukraine-controlled Donetsk’s oblast civil-military administration, said that Kyiv should seek the return of “’immemorial’” areas now within Russia, including Rostov, Bryansk, Kursk, and Voronezh oblasts and Krasnodar kray because the people there are Ukrainian in mentality and spirit.

The Russian reaction was quick to follow and had the unintended effect of highlighting the existence of Ukrainian communities in far more parts of the Russian Federation, communities Ukrainians have always called “klins” or “wedges,” thus making this back and forth into far more of a “wedge” issue than Moscow may like.

The first Russian politician out of the starting gates on this was Sergey Obukhov, a Duma deputy from Kuban. He called for Russian prosecutors to look into Zhebrivskiy’s remarks and noted that because of his own position, he could not fail to “react to the extremist statements of officials of a neighboring state who continue to say that Kuban is Ukrainian territory.”

In an article entitled “Ukraine from the Dnepr to the Amur,” Moscow journalist Andrey Ivanov interviews Bogdan Bezpalko, the deputy director of Moscow State University’s Center for Ukrainian and Belarusian Studies about Zhebrivskiy’s statement. What the scholar said will only add fuel to the fire.

![Mykhailo Hrushevsky, [Грушевський, Михайло; Hruševs’kyj, Myxajlo], 1866-1934. The most distinguished Ukrainian historian; principal organizer of Ukrainian scholarship, prominent civic and political leader, publicist, and writer. (Source: EncyclopediaOfUkraine.com)](http://euromaidanpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Hrushevsky-Mykhailo_photo-232x300.jpg)

Zhebrivskiy, the Moscow scholar continues, has simply developed notions of Ukrainian historians who confuse such cultural signs with political identity and loyalty. There were many such people “even in Soviet times,” and they “determined where people who in correspondence with Soviet nationality policy identified as Ukrainians.”

And from that, Bezpalko says, some of them argued that there where such Ukrainians lived are lands that “immemorially” are Ukrainian – even though these Ukrainians in most cases, he argues, never viewed where they lived as part of Ukraine and were loyal instead to the Russian Empire, the USSR, and now the Russian Federation.

“In the 1990s,” he continues, “many Ukrainian nationalists pushed such ideas. They published various maps showing Russia as a country which had fallen apart into several states.” They published books and “pseudo-scientific works.” But in doing so, they forgot that Ukraine had not always been “an indestructible whole.”

Bezpalko says he is “surprised” that Zhebrivskiy “did not include in the Ukrainian land the Gray Wedge and the Green Wedge,” the first of which is what Ukrainians who live in the Middle Volga call their region and the second is what some call Ukrainian settlements in the Russian Far East.

The notion that such places could be combined with Ukraine proper is “absolutely unrealistic,” he continues, and any talk about such things is only intended to encourage Ukrainians in Ukraine at what is a difficult time for them.

Like most Moscow people now, Bezpalko says that “Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians are one large people” and that today “Ukrainian identity has shifted from one based on blood or even culture” to one based on “ideology” alone. You are a Ukrainian if you support Ukraine regardless of your family background; you aren’t if you don’t.

“Today,” he says, “a struggle for the hearts and minds of people is going on so that they will choose this or that ideology.” And in that regard, Bezpalko says, Zhebrivskiy’s words constitute “a small dollop of danger.” Ukraine isn’t going to conquer any Russian territory, but such ideas sow “the seeds of doubt” among some.

That “ideological danger” must be fought, “above all by reviving our common Russian ideology,” one that “in contrast to Ukrainian nationalism,” the Moscow writer says, we base on genuine values and real heroes.” Ukrainians don’t have any and that is something Russia should constantly point out.

Russians should also point out that Ukrainian culture “has rural roots” and that whatever urban culture there was on the territory of the former Ukrainian SSR had “Russian, German or Polish roots.” Ukrainians refuse to see this and thus “Ukrainianism is like Russophobia” rather than a genuine national identity.

If one substitutes the word Russian for where Bezpalko uses the word Ukrainian, one can see how quickly his argument and that of the Kremlin collapses – and also how talk about Ukrainians and Ukrainian lands inside the current borders of the Russian Federation really can become a “wedge” issue after all.

Related:

- 1920 Memorandum to the Government of the United States on the Recognition of the Ukrainian People's Republic [at gutenberg.org]

- Ever fewer Ukrainians in Russia because of pressure to re-identify as Russians

- Ukrainians in Russia remember Ukraine's massacred elite

- Hatred being incited towards Ukrainians in Russia

- Russians repress Ukrainians in Far East and threaten to deport Crimean Tatars there

- Ukraine and Russia "share a long and common history" FAQ

- How Moscow hijacked the history of Kyivan Rus'