Russia continues its assault on the Crimean Tatars. On Wednesday, 13 April 2016, the so-called “prosecutor” of Crimea Nataliya Poklonskaya suspended the activities of Mejlis, the representative body of the indigenous people. According to Poklonskaya, these actions were taken “in order to prevent violations of the federal laws.” Earlier she demanded to recognize the Mejlis as an extremist organization, the case is under consideration now. Now, the representatives of the body are forbidden to hold mass public events, to use state and municipal media, use bank accounts and conduct any type of work. So what is the real reason for such actions?

During the last two years representatives of the Crimean Tatars have undertaken the most effective actions against the regime of occupation in their native Crimean peninsula. This vociferous opposition has a visible reflection on the actions of the Russian side.

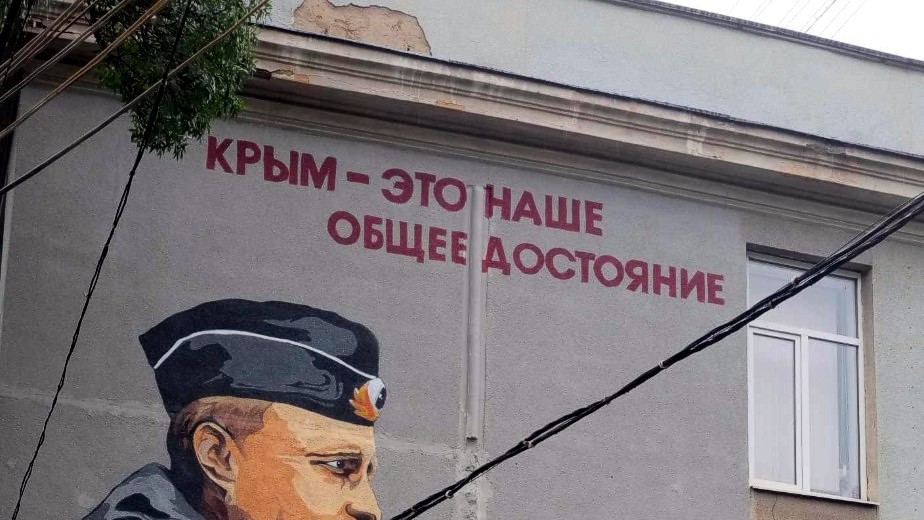

The occupation “authorities” suppress the opposition by political prosecution and the creation of myths.

Read also: Crushing dissent. Timeline of repressions against Crimean Tatars in occupied Crimea

In this regard another case against the indigenous people of Crimea has appeared. Activists call it the case of Hizb ut-Tahrir. In the summer of 2015, four young people were detained and accused of extremists activity and membership in the organization Hizb ut-Tahrir, which was forbidden in Russia in 2003. Tamila Tasheva, a Crimean Tatar and one of the founders of the NGO Crimea SOS, explains the details of the case:

“There is no fixed membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir. It is not an organization, it is the Islamic Renaissance Party. It is forbidden in some countries, mainly in post-Soviet countries with a dictatorial regime. However, in Crimea, Islam has never been radical, in principle, this party Hizb ut-Tahrir is not radical. They tell about the Islamic Caliphate through peaceful preaching. However, there was not many supporters of the party in Crimea. In general, no more than one percent of Crimean Tatars are orthodox Muslims. All the rest are secular Muslims. And now through this case of Hizb ut-Tahrir Crimean Tatars are being depicted as extremists. On February 11th, a series of home searches and arrests of faithful Muslims took place. Not all of them have any relation to Hizb ut-Tahrir, perhaps some of them, but not all. It should be noted that Hizb ut-Tahrir leaders knew that the party was banned in Russia at the beginning of the occupation and hurriedly left Crimea, so there are no (Hizb ut-Tahrir) leaders in Crimea now. Not long ago, one of the representatives of the “occupational authorities” said that indeed there is no extensive organization of this party on the territory of Crimea, however, the persecutions are still ongoing.”

According to Tamila, Russian myths about Crimean Tatars are actively broadcasted by propaganda and already gaining influence. Crimean Tatars are experiencing a rising hostility towards them from other people living in Crimea. Check out the most common myths on the indigenous people of Crimea to avoid falling into the trap of propaganda.

Reality: According to data presented by Boris Nemtsov in his report on Russia's war in Ukraine, there were about 35,000 Russian soldiers in Crimea at the time of the annexation. While the Ukrainian census of 2001 indicated that there were 243,000 Crimean Tatars in Crimea, the number of Crimean Tatar men between the ages of 18 and 60 was only about 73,000.

So it came down to 35,000 trained soldiers against a population of 73,000 unarmed, peaceful men.

Reality: The Crimean Tatar national movement was founded from the beginning on the principle of non-violent resistance, and it was with this strategy that they ultimately won them the right to return to their homeland. Perhaps the most notorious act of violence inscribed in the history of this movement was self-inflicted: the self-immolation of Musa Mamut in the summer of 1978.

Furthermore, among Crimean Tatar political and social organizations in Crimea, there was never a single one that used firearms in the 23 years following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Reality: In February 2014, Crimean Tatars allowed christians of Kyiv Patriarchate pray in mosques.

The Crimean Tatars are traditionally Sunni Muslims who follow the Hanafiyah school of Islamic law. It is widely believed among those who are unfamiliar with Crimean Tatar culture that they are comparable to Muslim groups in the North Caucasus in terms of their religious militancy. However, this is not true.

The vast majority of Crimean Tatars favor a Soviet model of behavior. Their culture is oriented more towards trade than militarism, and the degree of religiosity among most Crimean Tatars is comparable to that of average Ukrainians.

Reality: In the 23 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the number of conflicts in Crimea that could be labeled “ethnic” in nature could be counted on one hand. The most high-profile conflict reported by journalists as “interethnic” were not actually struggles between Crimean Tatars, Russians and Ukrainians, but rather confrontation between Crimean Tatars and local authorities, typically concerning the struggle for access to land.

When one party in a given conflict can be singled out by his or her nationality, it is often difficult to resist labeling the conflict as ethnic in nature. Such an interpretations is beneficial to the authorities because it creates the impression that they are not party to the conflict.

Reality: Such public organizations cannot act as opposition or alternative institutions. The Mejlis and the Kurultai are not “public organizations” and have never held this status.

These are the bodies of national self-government for Crimean Tatars.

More precisely, the Kurultai is the national parliament and the Mejlis is the national government. True, they are currently not incorporated into the framework of Ukrainian law, but they are nevertheless recognized by the Ukrainian Parliament and – most importantly – by the Crimean Tatar people themselves, who regulary elect Kurultai delegates and members of their local Mejlises.

Any attempts to put the Mejlis and any other type of Crimean Tatar public organization into the same category is unfounded.

Reality: No, definitely not! In Russian it is spelled as a single word (i.e., «крымскотатарский»).

Under the current “Rules of Russian orthography and punctuation,” the word «крымскотатарский» - “Crimean Tatar” - must be written together as a single word when used as an adjective. In Russian, hyphens are used to spell adjectives where the word “and” could be placed between the two words being combined to form a single adjective, However, “Crimean Tatar” is the only name for this national group, and it therefore can not be divided into “Crimean” and “Tatar”.

The myths were gathered in the Anthology of Modern Crimean Mythology which is a civic initiative of Internally Displaced Peoples from Crimea. The brochure is printed of the support of the Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine.