The Euromaidan protests are usually seen as the largest Ukrainian mass movement which changed society and the country. However, it was not the largest one in Ukrainian history. In the 90s Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts were shaken by the miners strikes. The miners of Donbas became an important political force which took important steps towards Ukraine's independence. Also, their movement could have given birth to a real civil society in Ukraine, but unfortunately it didn’t. So, what is similar and what is different between miners strikes and Euromaidan? Why did the former fail and how can the latter avoid the same mistakes?

The name of the Donbas region is a shortened form of “Donets Basin.” The Donets is the river which flows through the region. To Ukrainians, the “Donbas region” includes both Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, which together are generally considered a major industrial region. The territory of the oblasts is pocked with mines and for the long time miners were the main labor force in Donbas. In 1989 groups of miners protesting working conditions began to vocally disagree with the policies of the Communist party of the Soviet Union. This was the first wave of the movement.

Sergiy Shevchenko was a student, not a miner; but he was an active participant of the Donbas protest movement. He and his fellow students organized the political group based on the ideology of anarcho-syndicalism, according to which workers ought to get control of the economy and then use that control to influence the broader society. They were trying to promote their ideas in the miner's movement. Later, Sergiy and his colleagues set up a press and published the newspaper “Golos Truda” [The Voice of the Labor] which was designed to inform the movement’s members, unlike the official newspaper of the official trade union which was controlled by the Communist Party. Also Sergiy was one of those who discreetly tried to unite the miner's movement in the regions of Luhansk, Donetsk and Dnipropetrovsk. Recalling that time, he compares the ideas of Euromaidan and the earlier miner's movements.

Sergiy Shevchenko was a student, not a miner; but he was an active participant of the Donbas protest movement. He and his fellow students organized the political group based on the ideology of anarcho-syndicalism, according to which workers ought to get control of the economy and then use that control to influence the broader society. They were trying to promote their ideas in the miner's movement. Later, Sergiy and his colleagues set up a press and published the newspaper “Golos Truda” [The Voice of the Labor] which was designed to inform the movement’s members, unlike the official newspaper of the official trade union which was controlled by the Communist Party. Also Sergiy was one of those who discreetly tried to unite the miner's movement in the regions of Luhansk, Donetsk and Dnipropetrovsk. Recalling that time, he compares the ideas of Euromaidan and the earlier miner's movements.

“I see many commonalities in the ideas - If one takes into consideration only the grass-roots ideas, not those which are voiced by the politicians, but those ideas that people wanted. They wanted to live a worthwhile human life. It is the simplest idea in a movement. They wanted what we now call self-organization. So that one can solve problems by himself or herself with his peers, but not with the authorities who would not do anything anyway.”

Part one: Great Hopes

The first miners protests started in Kuzbass, Siberia in the summer of 1989. Than the initiative was endorses by other parts of the USSR. The First Congress of the miners of the USSR took place in Donetsk in the summer of 1990. At that time miners were the working elite, with some of the highest wages in the country. However, they could not buy anything with these wages because the shelves in the shops were empty. This was one of the main reasons for disaffection among the Soviet people, and the miners expressed this dissatisfaction. During the First Congress of the miners, the participants also made political demands.

First, they demanded that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union would no longer have its leading role. According to the

6th Article of the Constitution of the USSR the Communist Party played the leading role in forming political, cultural and ideological life of Soviet society. It also meant the party exercised total control over people’s lives. Changing this article would have totally changed the structure of society.

“So the first wave of miners' strikes had political point, it was against the monopoly on ideological and spiritual life. They also wanted to separate production from ideology. There have been very powerful ideas about (workers) self-organization, but totalitarian regime can not exist together with (workers) self-organization”.

The second demand was to ratify the economic independence of Ukrainian SSR. At first miners were talking about autonomy in forming the budget of the Republic, but it was the first step towards total independence for Ukraine. The miners were also demanding the independence of the worker’s movement from the Communist Party.

The second Congress of the miners of the USSR was held in October 1990, also in Donetsk. The miners became more confident and this time they decided to unite all miner's movements into one process. At that time there was a system of state trade unions, but it did not serve the interests of the working class. So the miners created an Independent Union. At first, the Union was the same organization in both Ukraine and Russia. Later, when there was no Soviet Union, Ukrainian activists conducted their own Congress. The miner's movement was functioning parallel to the Government’s structure. The leaders of the movement used to solve all the problems with which volunteers are dealing nowadays. Just like today, society did not want to be ruled by oligarchs, but at that time they did not use this word. The Communists Nomenklatura (the highest levels of the Communist Party) were playing the role of oligarchs. Later, these people merged with criminal circles in the newly-independent Ukraine, and that is how the country received its new political “elite”.

Part Two: The Great Disappointment

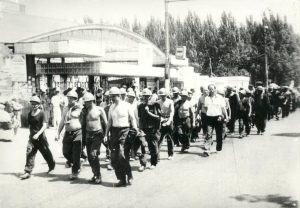

The next wave of activity started in 1993. The expectations people had after the collapse of the Soviet were not fulfilled. The country faced hyperinflation and the miners faced a new problem: poverty. However, they were not alone. Teachers, doctors and other specialists could also barely make ends meet. In 1993 the largest strike in Ukraine's history was started in Donetsk. A million and a half people of different professions came out onto the streets. The miners were in the core of the strikers. The city of Donetsk was covered with people in hard hats. The protests became permanent.

During this period the idea of economic autonomy of Donbas was actively supported. However, this was not “separatism” as there were no anti-Ukrainian aspects of this idea. Moreover, at that time the miners were hated by the Communists, who accused them of destroying the Soviet Union. Autonomy for Donetsk workers at that time meant that the oblast could feed itself.

“

There were demands for the autonomy of Donbas - but do not be confused with the current requirement for the autonomy of Donbas. These are two different things. Then, the idea was to allow the oblasts of Ukraine to determine their own budgets. In fact, yes it's decentralization. We understand that now what is meant by “decentralization” is creating new centers that will eventually result in losing control over Ukrainian territory. That time there were no separatist ideas like we are with Russia, it was not that like. These words sound the same, but the meaning was different”, says Sergiy.

The coal mining is very important for the region and especially for the cities which are centered around large industrial enterprises. So that when on top of all the other problems of the mid-90s, many mines were closed because of the demands of the IMF, it became a real tragedy. Many small cities in Donbas withered away.

The people in power in Kiev found a way to give hope to the Donbas miners: by making the miners’ leaders representatives in the Ukrainian central government."

Part Three: The Final Compromises

The hope brought by sending representatives to Kiev could not last forever. Inflation was growing. People were receiving millions in cash but could not buy anything with it. With a month’s wages people across the country could buy only a week’s worth of products. The situation was aggravated by the fact that workers stopped receiving their wages. There were mines were people have been paid their full wage for 12 months. Some months they received part of their pay, sometimes they did not receive any. The people of the country were working as slaves without any guarantees that they would eventually be paid. Some found a way to at least feed themselves and their families by stealing, for example, metal from factories. And these were people who did not usually steal.

In this catastrophic situation, the miner's movement served as a kind of constraining factor for the political elite. The miners were fighting for their rights and for the rights of millions of their fellow citizens.

In 1996 the Strikes Committee called for new protests. Thousands people from the mines came on to the streets again, but it did not help. They then started to block railways and highways. They stopped the traffic arteries all across Donbas. There was no transport around Donetsk. Only ambulances and trucks with bread and some necessary products could reach the city.

In a manner almost the same as what took place during the Euromaidan and Orange revolutions, pro-governmental militias were also present in the Oblast, waiting to disperse the protest movement. That time this coercive power was not used and only the leaders of the movement “paid” for the protests when they were arrested.

Also the TV propaganda machine was working against the miners. They were depicted as people who did not want to work, and journalists were saying that going on strike was criminal. Meanwhile in 1997, the court proceedings against the leaders of the miners’ strikes started. They were accused with anti-governmental actions. The movement could not survive without its leaders, and that is how railway strikes ended.

In 97-98 the movement was already dying. However, one episode of the strikes in Luhansk region which is not often mentioned in Ukrainian history is worth examining. In the summer of 1998 miners from across the oblast organized a permanent protest in Luhansk. They set up a camp and people rotated in and out of the camp. Their demands were simply to receive what they had earned. This protest was dispersed by the Berkut, the unit which is now sadly famous for attacking Euromaidan activists.

"...The Berkut attacked the people. There were shouts. Sticks were flashing in the air, they beat heads and shoulders. People were knocked down. All the strikers merged into a shouting clump of about 100 men with a large dark blue epicenter. 6 or 7 Berkut surrounded every miner knocked to the ground ...”, wrote a member of the Independent Miners Trade Union about the events of 24th of August 1998. A few months later the movement experienced another sad event. One miner burned himself alive in protest against the sardonic policy of the mine where he used to work.

Even though at that time the miners started protest marches towards Kyiv, the movement was dying. Sergiy described the mood of the people in late 90s:

“People were tired. They did not believe anyone. It seems that they wanted to, but they already could not. This was the period when the leaders of the miners movement started to participate in elections. They started to create political alliances with unworthy political parties. For example, one of the leaders of the Strike Committee, the legendary Mykhail Krylov, who had been in prison in 1996 because of the protests, formed a bloc with people whom we now call oligarchs. They were the people who were ultimately responsible for our lack of wages, who were ultimately responsible for mine explosions taking place because of security lapses, who were ultimately responsible for our poverty. It was the period of degradation for the miner's movement, when its leaders started to be interested in their political careers, and not in the interests of their constituents, who chose them to be leaders of this movement”.

Still, some protests took place in the 2000’s, but they were not influential. The main role of the movement in history was to lead Ukraine towards independence. Nevertheless, more than a decade of the fighting for their rights did not bring miners anything except the false compromises.

The story of the miner's movement teaches us a lot. Looking deeper into it, today’s activists can learn how to avoid repeating the miners’ mistakes and ensure that the spirit of the Euromaidan protests remains effective.

This historical story is based on the lecture conducted by Sergiy Shevchenko in the center for the displaced "The House of Free People" In Kyiv.