The Dutch Safety Board, legal representatives of victims and journalists have accused Ukraine that its authorities failed to close its airspace – and implicitly argued the disaster would have not happened if they would have done so. Here we present eight reasons why that accusation is not so justified.

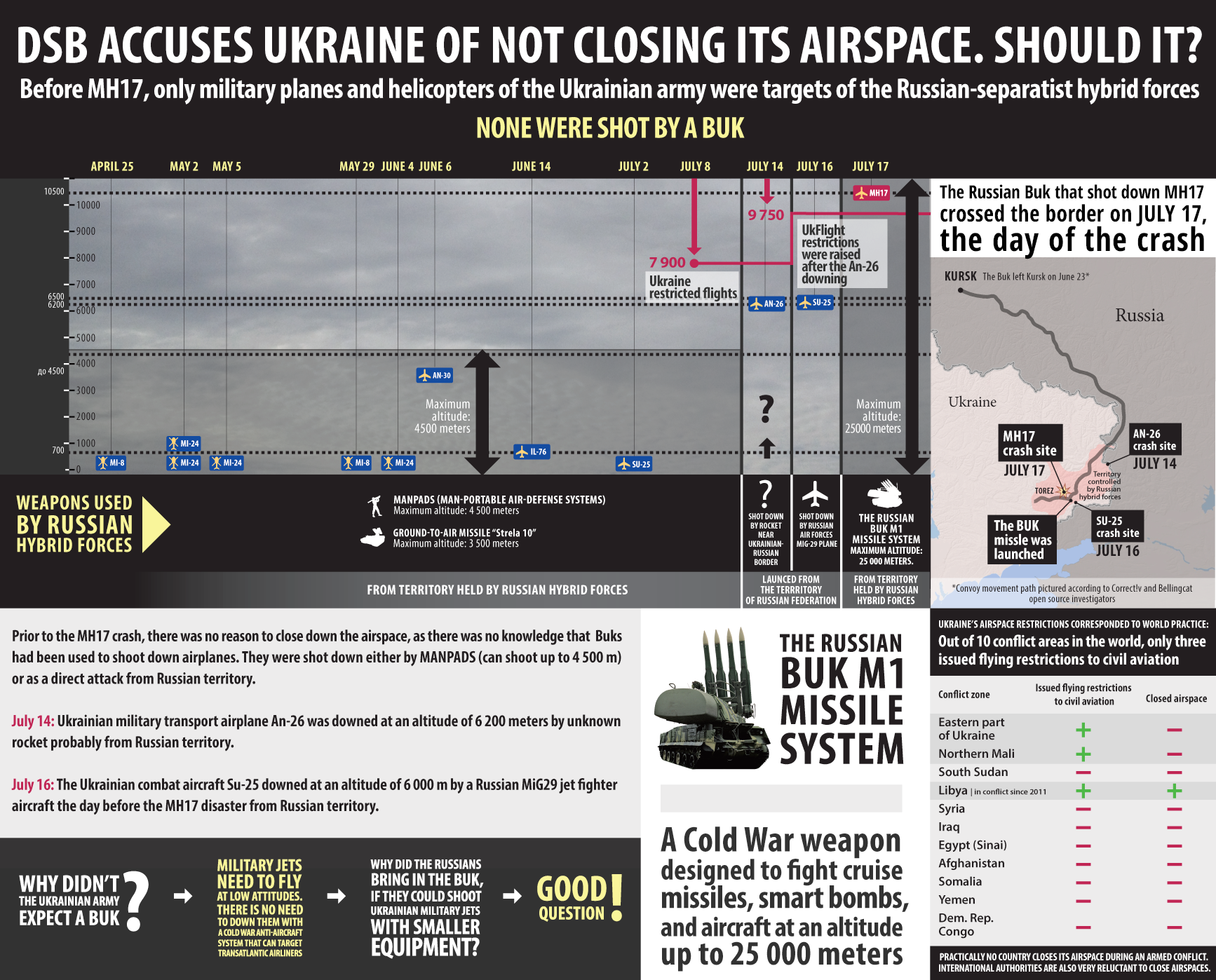

One. Before the shot-down of MH-17 there had been not a single indication that there had been any danger to any airplanes flying above 10 000 meters (i.e. the height passenger planes had been using). No airplane had been shot down at this height, and no adequate weapons systems - for example the Buk-system - had been used prior to the 17 July 2014.

Two. The two Ukrainian military airplanes that were shot down at a considerable height on 14 and 16 July were still flying under 10 000 meters, also in order not to endanger civil aviation, and there was no need of using a Buk (the Pantsir-system probably used in one case is most effective under 10 000 meters).

Three. Ukraine had only three days to assess the situation, and no reason to believe that passenger jets would be targeted as only surface-to-air systems effective under 10 000 meters had been used.

Four. The exclusive target of Russian air-to-air or surface-to-air missiles had been the Ukrainian military, and no Ukrainian civilian flights were targeted; the last two military jets that were shot-down being targeted from Russian territory.

Five. Practically no country closes its airspace, even if there is war (see the example of Libya). If there is no obvious threat to passenger flights, the airspace remains open. We can also take the recent example of Russian cruise missiles flying over Iran and posing a threat to civilian aviation – nobody has closed civilian airspace.

Six. Also international authorities are very reluctant to close airspaces, the recent case of the Russian cruise missiles launched from the Caspian See, targeted at Syria (and four of them landing in Iran) has not led to specific measure. The European Aviation Safety Agency for example gave no specific recommendation to avoid the airspace between the Caspian Sea and Syria, and some airlines – such as the Australian Quantas – continued to fly over Iran.

Seven. There had been no reason to use a fairly complicated surface-to-air missile system (such as the Buk that normally requires professional – Russian – staff and a target acquisition radar, plus the launcher vehicle), just because Ukrainian jets could be targeted with other systems more effectively.

Eight. In fact the problem is not that the Ukrainian airspace had not been closed, but the presence of a Russian Buk on occupied Ukrainian territory without a reason. Why would someone transport this sophisticated system into enemy territory, not needed in order to shoot down military jets? And here we see, there is only one answer to this question: Russia’s Buk being present in Snizhne on 17 July 2014 was part of a “special operation” and has to be seen as being out of context with actual warfare against the Ukrainian military.