Ilya Frank, a Jewish linguist whose approach has defined how Russians study foreign languages for more than a decade, has decided he and his family must leave Moscow for Israel because of what he describes as “a Nazi-like atmosphere” there, one he quickly identified because of his familiarity with German writings and films from the 1930s.

In an interview posted online yesterday with Dmitry Volchek of Radio Liberty, Frank, 52, says he decided to leave “in the first instance” for political reasons because he did “not want to life in a country where 90 percent of the population is infected with the virus of self-love and hatred to others.”

“I am leaving because of the Nazi-like atmosphere which has emerged in Russia and in which it is very unpleasant to live,” Frank says. He doesn’t have a television and works at home but when he does go out, he sees “the slogans, hears the conversations, and sees what books are being offered at major bookstores.”

Because he is “by education a German instructor,” he continues, he has “read many German books about the 1930s in Germany, watched documentaries, and listened to Goebbels in the original” and thus can “see parallels and this is very unpleasant,” especially because his six-year-old daughter will be entering school next year and would be exposed to all that.

Frank rejects the argument of Vladislav Inozemtsev that Russia today is more like Mussolini’s Italy than Hitler’s Germany and that of Maksim Frank-Kamenetsky that there is no anti-Semitism in Russia. While Russia now may resemble fascist Italy, he says, it also has “undoubted parallels” with Nazi Germany, including the language of its leaders.

And while there is less state-sponsored anti-Semitism in Putin’s Russia than in Hitler’s Germany, there is ever more exploitation of and even promotion of anti-Semitic themes by those close to the regime such as Archpriest Dmitry Smirnov who invariably stresses the Jewishness of what he sees as Russia’s opponents. That sends a message to those ready to hear it.

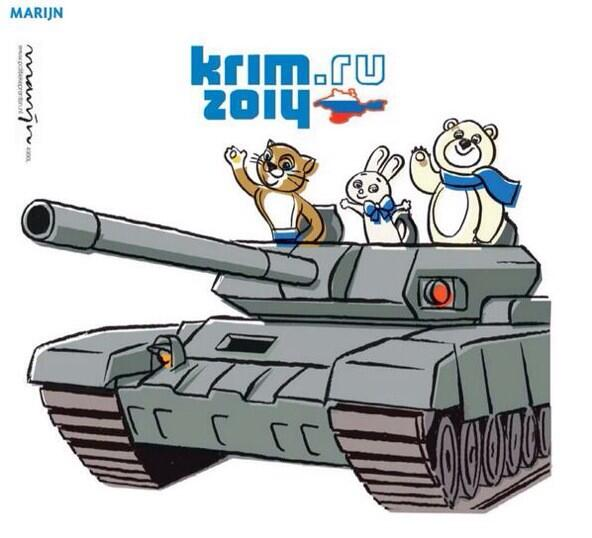

Frank says that he did not feel himself “alien” in Russia until the “Crimea is Ours” campaign began and “90 percent of the population supported this fascist policy.” But now he does, and because his desperately ill mother has now died, something that had made his departure impossible, he and his family are now leaving.

According to the linguist, there are three possible courses of action: to struggle with the regime, to leave, or to sit quietly and hope for change. He says he has chosen the second because he does not see “any sense in struggle with a regime when almost the entire population of the country supports it.”

Frank agrees that he cannot bear “the new language” which has appeared in Russia over the last 18 months. He adds that he believes that “people educated in any society sensed this when the Stalin era arrived. For them it was unbearable because they saw this stupidity which was expressed in language, in conversations and in slogans.”