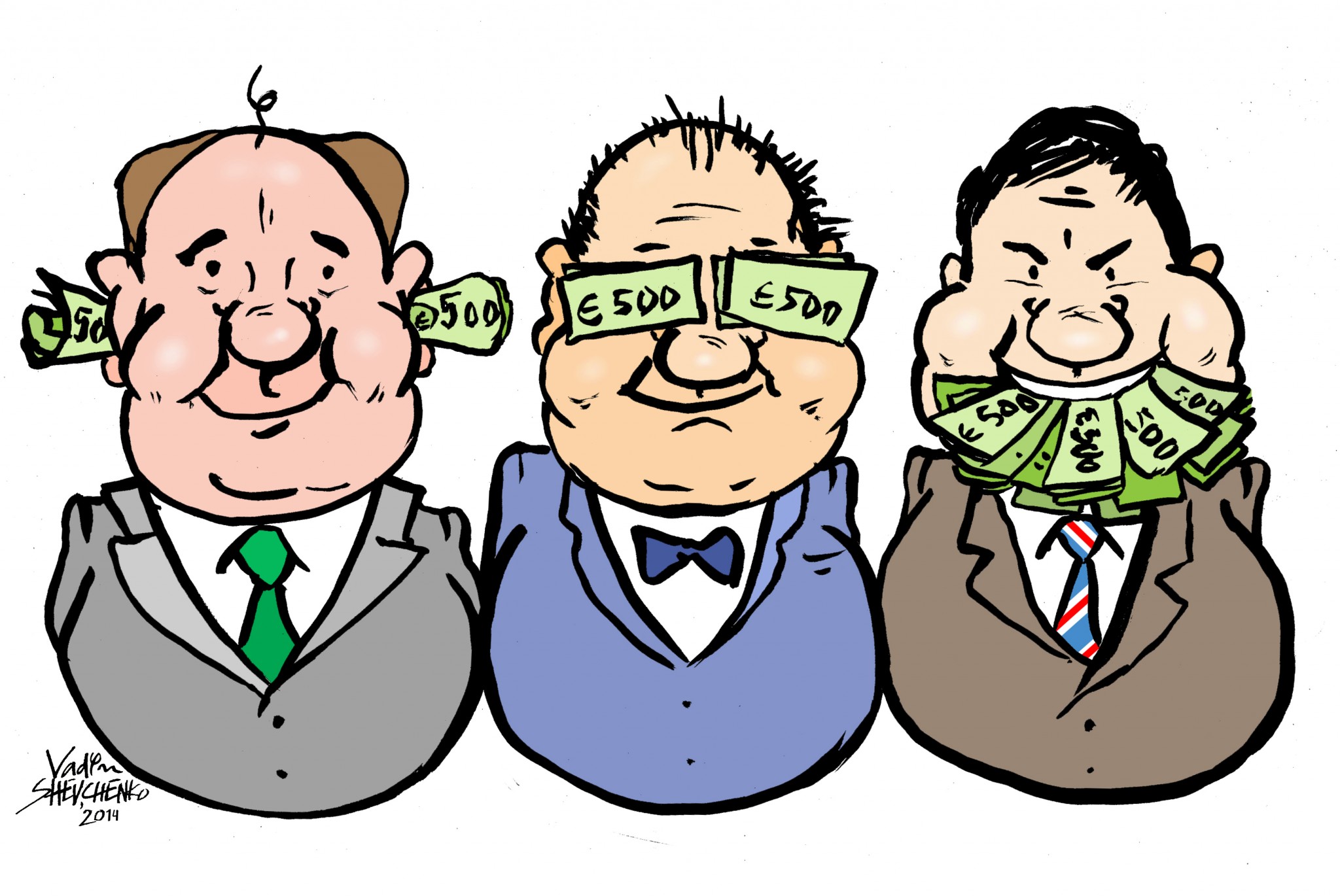

One year after Viktor Yanukovych was ousted, his methods remain firmly entrenched in the reality of Ukrainian life. Despite the country’s Revolution of Dignity and continued Russian aggression against Ukraine, local oligarchs have become even more powerful and influential, and pose a significant threat to Ukraine’s European development. Oligarchs control the state apparatus, mass media, and whole sectors of industry. Therefore, they can simply put the brakes on reform as soon as their financial interests are threatened.

Under the previous government, the oligarchs were strictly subordinated. Yanukovych was the “super oligarch”, the main beneficiary of the regime. Below him came the traditional oligarchs, who had to share their profits with Yanukovych. Rinat Akhmetov, for instance, was granted control of metallurgy and energy, Igor Kolomoisky had the oil industry, and Dmitry Firtash and Sergei Levochkin controlled the gas, chemical, and titanium sectors.

Last year, after Yanukovych’s flight, the oligarch clans lost their patron – but they gained the chance to extend their personal power.

Now, one year after the Revolution of Dignity, a few have seen their influence diminished, but only because Yanukovych is gone, not because reforms have been made. The oligarchs soon found a common language with the victors of the Maidan, providing them with financial help, access to television channels, and votes in parliament. This unofficial pact prevented the eradication of the clans’ wealth-generating systems, traditionally powered by corruption, conspiracy, and crushing competition.

A disoriented and weakened state apparatus proved unable to oppose the oligarchs. The new government lacked the political will to break with its predecessors’ schemes. No real economic reforms were introduced to give new impetus to small and medium-sized enterprises, the only real potential challengers to the oligarchic order and guarantors of democratic reforms.

The government has blamed the ongoing war for the failure to implement reforms. However, it is difficult to accept that the war necessarily prevented the government from implementing fiscal reforms, simplifying business rules, dismissing corrupt traffic police, or setting up sanitary-epidemiological services, as borne out by the model of Georgian reforms after the Rose Revolution in 2003.

Yanukovych’s clan

After Yanukovych fled Ukraine, the EU imposed sanctions against 18 individuals who embodied the old regime. The list included Yanukovych himself along with his two sons Oleksander and Viktor Jr, other former government members, and Serhiy Kurchenko, the man behind multiple business schemes for the Yanukovych family.

Interestingly, none of the influential oligarchs who accumulated wealth during Yanukovych’s reign were on the list.

The heaviest losses were sustained by Yanukovych’s clan, headed up by his eldest son, Oleksander, who assigned key posts to his friends, Serhiy Arbuzov, Oleksander Klymenko, and Vitaliy Zakharchenko. Their accounts in Europe were frozen and some of their assets were blocked. In Ukraine, however, the Yanukovych family assets were mostly in the hands of “straw men”. The family’s main path to wealth was not acquisition of private property, but corruption and appropriation of state assets. This explains why the losses incurred by Yanukovych’s circle are still inconsiderable.

The All-Ukrainian Development Bank, which served as a shop front for Yanukovych’s son’s business, ceased its activities only in December 2014, after the introduction of an interim administration by the National Bank of Ukraine. Donbasenergo, a company that held two electric plants privatised to benefit Yanukovych’s family, continued to receive payments throughout 2014.

Financial institutions belonging to Yanukovych’s circle carried on functioning throughout 2014. One example is Unison Bank belonging to former revenue minister Oleksandr Klymenko, Kurchenko’s business partner and the main paymaster of the Yanukovych family.

Yanukovych’s subordinates’ media empires are still operating. None of the publications by Kurchenko’s Ukrainian Media Holding group have been stopped, Zakharchenko-linked television news channel 112 continues to broadcast, and, in Kyiv’s metro, people are still queuing for Vesti, a free newspaper associated with Klymenko.

Even with Yanukovych’s people removed from their posts, corrupt courts of justice have continued to pass judgement in the former president’s favour: for example, one of the snipers who targeted people at the Maidan was released from house arrest, Arbuzov’s money in Ukrainian banks was unblocked, and the decree forbidding Ukrainian state payments to the electric plants owned by Yanukovych’s family was cancelled.

In January 2015, Yanukovych was placed on the Interpol wanted list, accused of economic crimes. But Yanukovych was instrumental in reducing, by $30 million, the financial obligations of a company that went on to buy the state telecommunications company, Ukrtelecom. The new owner of Ukrtelecom also appears to be associated with the Yanukovych family.

Akhmetov and Firtash

Rinat Akhmetov’s clan’s influence has diminished because of Ukraine’s loss of control over the occupied part of the territories of Donetsk and Luhansk. These regions constituted Akhmetov’s political and industrial base. Compared to 2014, Akhmetov’s influence in parliament has considerably decreased. In the previous administration, he had control over several dozen Party of Regions MPs, as well as a number of key ministries, state monopolies, and regulators. Today, no more than 20 deputies from Akhmetov’s camp are in the Opposition Bloc faction, formerly the Party of Regions. Some of his long-term allies have defected to the clan of his rival, Ihor Kolomoisky.

The legislative initiatives of Akhmetov and his people in parliament have no chance of being approved, since none of his contingent heads up any of the parliamentary committees. Today, the oligarch’s main resource is his good relationship with Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, who has taken no steps in the past year to limit Akhmetov’s voracious appetite. Akhmetov’s enterprises continue to reap benefits in the industry and energy sectors, while the dubious privatisation that took place under Yanukovych goes unquestioned. Akhmetov even managed to acquire the thermal power plants Zakhidenergo and Dniproenergo through tender offers in which his supposed competitors only pretended to fight for the assets.

As a result, Akhmetov now owns 70 percent of Ukraine’s thermal energy, and fixed tariffs guarantee him stable profits. He survived Yanukovych’s flight from the country because of his willingness to share his money with all the political parties, as well as his far-reaching media holdings. He even succeeded in coming to an arrangement with the terrorists occupying Donetsk. His luxurious mansion stands intact in a town ruled by gangs of heavily armed “marginal” and Russian fighters.

Today, Akhmetov’s problem is the absence of a brilliant political leader to replace Yanukovych and spearhead his revenge. This is another consequence of the perverse political culture of the Party of Regions, in which the absence of internal competition has led to a shortage of party officials.

Another oligarch clan, centred on the corrupt gas broker RosUkrEnergo, incurred much greater losses after Yanukovych’s escape. However, American law enforcement agencies rather than Ukrainian actions made this happen: at their request, Dmytro Firtash, one of the group’s leaders, was arrested in Vienna. Firtash is now trying to avoid being extradited to Chicago, where he faces imprisonment. He has hired a group of influential American and Austrian officials to act on his behalf, including a former Austrian justice minister and the former Secretary of Homeland Security, Michael Chertoff. Firtash wants to stay in Austria as long as possible; there, he is allowed to move freely within the country, while trying to settle his US criminal charges with the help of American lobbyists.

Firtash was held in custody for almost two weeks, then released on bail after paying €125 million, the largest sum in Austria’s history. But these were not his only losses. Last year, he lost Nadra Bank as well as control over the titanium deposits he acquired under Yanukovych. Ukraine’s prosecutor general has opened a criminal case over the fraudulent sale of Inter, Ukraine’s leading television channel. Meanwhile, Firtash continues to wield control over two dozen deputies, including his close business partners, Sergei Levochkin and his sister Yuliya Levochkina, Yuriy Boyko, and Ivan Fursin.

Ukraine has not managed to eliminate one of the main elements supporting corruption: the differential in gas prices for households and industrial complexes, which can vary tenfold. Firtash still controls the largest network of gas distribution companies, where cheap gas destined for the people is “lost”, but then reappears in his chemical plants that produce fertilisers sold at international-level prices. This is the source of his great financial wealth.

Kolomoisky and the new oligarchs

Ihor Kolomoisky’s clan significantly increased its sphere of influence after Yanukovych’s fall. Kolomoisky tries to present himself as a staunch opponent of Yanukovych, but this is far from the truth. He was ready to establish relationships with any authority and, before the 2010 elections, he decided to bet on Yanukovych, assisting him financially through his old friend Yuriy Ivaniuschenko. By doing so, he kept control of Ukrnafta, despite the fact that the state owned the majority of its shares. Kolomoisky was one of the main beneficiaries of Yanukovych’s regime and even attended the former president’s private birthday celebrations.

After Yanukovych’s departure, Kolomoisky’s strategy was to bet on his own political authority. Instead of spending money on external political projects, he invested in himself and became head of Dnipropetrovsk province, neighbouring the Donbas region occupied by Russian troops.

Kolomoisky created battalions of volunteers to defend the borders of Dnipropetrovsk province, and sometimes to act as private security for his organisations. They were even involved in corporate conflicts. For instance, they confiscated petroleum products belonging to Kurchenko.

In the new parliament, Kolomoisky’s people have infiltrated various factions. They can be found in the Petro Poroshenko Bloc and the Popular Front, and among the unaffiliated MPs. Kolomoisky continues to control Ukrnafta, the oil refinery in Kremenchuk, and a network of state-owned pipelines. Immediately after Yanukovych’s fall, raw material from these pipelines was processed in Kolomoisky’s plant. He also controls Odesa province, governed by Ihor Palytsia, a former top manager of Kolomoisky’s Ukrnafta. Kolomoisky’s media empire, which includes the 1+1 television channel, is used to settle political scores.

Kolomoisky was fired by Poroshenko in March 2015, when as governor of Dnipropetrovsk province he crossed the line in using public resources for his own enrichment. He refused to pay dividends of 1.8 billion hryvnia (approximately $70 million) to the state budget from Ukrnafta. Kolomoisky said he would “never pay the dividends” in spite of the fact that the government owns 50 percent plus one share in the company.

He also violated the law that prohibits dual citizenship, because he actually has not even two but three passports – from Ukraine, Israel, and Cyprus. And he involved former battalion fighters in protecting his management in Ukrnafta after legal changes that allowed the removal of the company’s pro-Kolomoisky CEO.

The arrival of armoured personnel carriers and automatic weapons on the city’s streets had looked like the first act of a military coup.

Kolomoisky placed in doubt the president’s monopoly on the use of force and undermined the legitimacy of Poroshenko and the whole government. It was a point of no return and his resignation was unavoidable. Kolomoisky has, in other words, been prevented from grabbing even more power; but it is still a key member of the oligarch system which survives intact.

This last decade has seen the almost invisible emergence of a new breed of oligarchs in the agrarian sector. The land reserves of Ukraine, their prime location, and the preferential treatment given to agriculture have all contributed to the rise of these magnates, whose fortunes can now compete with those of the “old” oligarchs.

Their rise is reflected in the composition of the current parliament, which includes relatives and representatives of the main agrarian empires, including the son of the owner of Nubilon, the brother of the owner of Kernel, and lobbyists for the Myronivsky Hliboprodukt, UkrLandFarming, and Cargill corporations.

After the 2014 elections, when parliament sat for the first time, there were eight candidates to head the committee on agrarian policy in Poroshenko’s faction alone. The agrarian lobby, which had until then acted from outside parliament, was now firmly established in legislative structures from where they could lobby for corporate interests.

How to move forward

More than anything, Ukraine needs to find a way of reducing the influence that oligarchs have on all aspects of life. This might take years, but if it does not happen, it will be impossible to build a fair and just society without corruption at the highest levels of government.

The oligarchs’ financial influence over politics must be removed.

The oligarch clans are currently important sponsors of political projects that are profitable for business, making Ukrainian elections some of the most expensive in the world. To weaken their influence,

Ukraine should introduce state funding of political parties. This is a system that has been implemented in the majority of European countries, where parties receive yearly grants funded by taxpayer money to cover their expenses. Money from the state budget should become a real alternative to that from the oligarch clans.

Today, rivalry between the parties looks very much like a virtual purchasing power competition. Campaign teams buy airtime on television channels at great expense. One minute on the STB channel belonging to Viktor Pinchuk, son-in-law of former President Leonid Kuchma, cost between $15,000 and $20,000 during the last elections. Campaign teams would buy hours of airtime and accept the oligarchs’ people on their lists in order to get discounts.

A major step towards reducing the oligarchs’ influence, therefore, would be limiting or even banning political advertising on commercial channels. Advertising for political parties should be restricted to free slots on public television. This would encourage politicians to engage in new forms of communication with the electorate, face-to-face rather than through televised broadcasts.

Financing parties from the state budget and limiting political advertising would be a start, but it would by no means be enough. It will be impossible to curtail the oligarchs’ influence over society without reforming television. Eighty percent of the population rely on television for information. Ukraine should, therefore, create a public state television channel, supervised by a board to ensure its impartiality, which would not only give citizens an alternative source of information, but would also force the oligarch-controlled channels to cover information more objectively. Biased news, if competing against a comparatively unbiased viewpoint, would become less influential and popular.

Equally important is the reform of justice, which today does not serve the needs of a modern Ukraine. However, these complex reforms will only be achievable if Ukrainian civil society finds a permanent ally in Western governments and international institutions. Ukrainian officials and politicians are sometimes deaf to the demands of their citizens, but become much more receptive when these demands are reiterated by organisations providing financial assistance to Ukraine. Therefore, including anti-oligarchic measures in a reform package might well be the greatest service that European institutions could provide to Ukraine.

Other articles from this series:

Serhiy Leshchenko: Sunset and/or sunrise of the Ukrainian oligarchs after the Euromaidan revolution?

Volodymyr Yermolenko: Russia, zoopolitics, and information bombs

Anton Shekhovtsov: Spectre of Ukrainian "fascism": Information wars, political manipulation and reality

Olena Tregub: Do Ukrainians want reform?