“Moscow is not prepared to offer [Russia’s] regions freedom analogous to that which it is demanding for [Ukraine’s] Donbas,” despite the fact that Russia is nominally a federation and Ukraine is constitutionally a unitary state, according to a lead article in today’s “Nezavisimaya gazeta.”

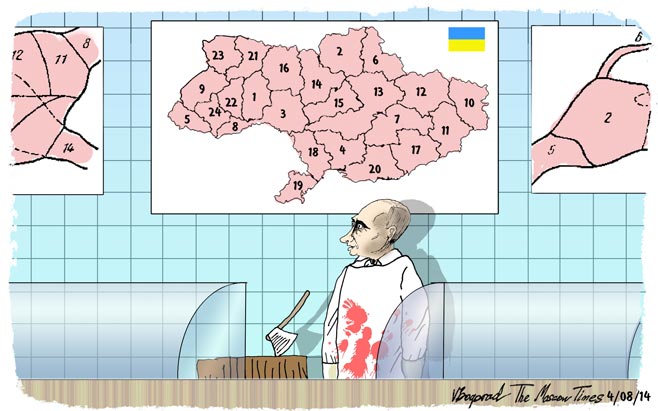

In an editorial entitled “Is the Russian Federation Federal?” the editors note that Moscow is demanding Kyiv offer broad rights to its regions – although few in the Russian capital talk about extending such rights to regions of Ukraine other than those Russian-speaking ones in the east.

Kyiv has consistently responded that there isn’t going to be any federalization at all, the editors say. For the Ukrainian authorities, it is a matter of principle that “Ukraine is a unitary state and that it will agree only to decentralization, that is, to the delegation of part of the authority from the center to the regions.”

Moscow considers that “insufficient, unconstructive, a dead end, and something which will lead to the escalation of the conflict between Kyiv and the Donbas,” although such an approach is exactly the one Moscow has adopted in its dealing with its own republics and regions.

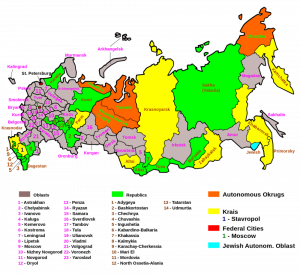

And that is the case even though “Russia in distinction from Ukraine is a federation” by its constitution and is much larger and more diverse ethnically, linguistically, culturally and historically than is Ukraine.

Indeed, at the present time, the Moscow paper continues, “it is impossible to imagine that any of the regions of Russia” could have an independent foreign policy. They cannot even have political parties based on ethnicity, something that in a genuinely federal state would be “completely normal.”

The real as opposed to constitutional nature of the Russian state is shown, the paper suggests, by the reaction to Chechnya’s proposal to allow polygamy. Russian anger on that score is completely logical if Russia is a unitary state but it would be illogical if Russia were a federal one.

This is not to say, the editors continues, that polygamy is “a sign of federalism.” Rather, it is to insist that “under conditions of de facto unitarism, a region will talk about its rights and freedoms by means of the most challenging jests, which demonstrate the radical difference,” something that it would not be as inclined to do in a genuine federation.

“Kadyrov’s Chechnya has thus in fact declared that it has won the right to be distinctive, even though by form it is part of a unitary model, with a single language, flag, educational system, branches of United Russia Party and even a Putin Street. But [Moscow] considers that Chechnya has not won anything” and that its efforts in this direction have been defeated.

Many in Russia argue for a unitary approach because many regions and republics, including Chechnya, receive subventions from Moscow, forgetting of course that that could have been avoided at least in the case of that republic if the center had agreed to allow Grozny to keep the profits of its oil industry.

But that is a lesson Moscow has not learned at least for itself, that it might have been possible to avoid the worst “polygamist excesses” by allowing the development of genuine federalism.

The “Nezavisimaya gazeta” editorial is important not only for the logic it outlines and for the way in which it underlines the Kremlin’s hypocrisy but also because it shows one of the ways in which Vladimir Putin may unintentionally bring the Ukrainian conflict back into the Russian Federation itself.

While Kremlin propagandists and many others in both Russia and the West will have no difficulty maintaining these two contradictory approaches in their own minds or at least discourse, others in Russia, Russian and non-Russian alike, will see Moscow’s push for federalism in Ukraine as an occasion for them to push for it in their own country.

To the extent that happens – and there is evidence among both ethnically Russian regions and the non-Russian republics as well – the most serious consequence of Putin’s campaign for the federalization of Ukraine may be demands for real federalism in a country that is constitutionally supposed to have it already, his own.

And if as seems certain the Kremlin leader opposes such efforts, the outcome could be truly serious indeed. After all, as many seem to have already forgotten, the USSR did not fall apart because Mikhail Gorbachev allowed power to flow out of Moscow to the republics but rather when, after having done so at least rhetorically, he tried to take it back.