Yuliya Latynina argues that Russia, many of whose residents view it as the third Rome, may suffer the fate not of the first Rome but of the second, a fate that cannot be reassuring to many of them because in the end the residents of the second Rome in Constantinople “considered that Islam was better than the West.”

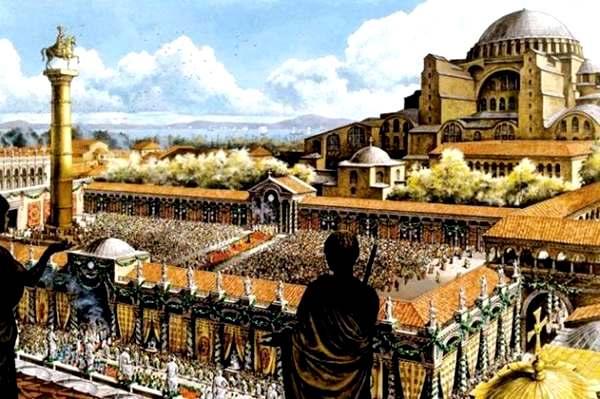

In a 3300-word essay in “Novaya gazeta” over the weekend, the Moscow commentator and Ekho Moskvy radio station host said that it is becoming obvious that under Vladimir Putin, Russians are being encouraged to think of themselves as “the heirs of spiritually-rich Byzantium,” the traditional “Second Rome” in Russian thinking.

But Latynina argues that there are seven important reasons why Russians ought to avoid thinking that they are in a situation like the Second Rome and should be questioning a government that promotes that notion, however much they believe in Filofey of Pskov’s 1510 claim that “Two Romes have fallen; the third stands; and there will not be a fourth.”

First, as she points out, “’Byzantium’ as a country never existed.” It called itself the Roman Empire or the Empire of the Romans.” In antiquity and for the rulers in Constantinople, she points out, “empire” referred to a single state rather than being one among many. As a result, there is no agreement on when it was created, something “unique” in world history.

Second, as Latynina says, Byzantium, the “Second Rome,” despite being the heir to classical Greece and Rome, “did not create anything” that people today take seriously. “If you are not a specialist,” she continues, “you won’t have read anything” produced by it, “not great novels, not great poets, and not great historians.” It was a truly “fruitless” enterprise.

“The high spirituality of the Empire of the Romans, as is well-known, ended when even on the eve of its collapse,” Latynina points out, fanatics from the church and from among the population “did not want to count on the help of the West. Better Islam, they decided, than the West.”

Third, “the Empire of the Romans never developed a mechanism for the legitimate transfer of power.” As a result, it was constantly weakened by struggles for power and thus was not in position to defend its interests against threats from outside its borders.

Fourth, and related to the third factor, Byzantium lacked an effective bureaucracy capable of ruling the country. Fearful of being challenged by almost anyone, its rulers periodically destroyed the institutions of the state and thus prevented the establishment of “a stable code of rules and a mechanism of administration.”

“The Empire of the Romans did not develop any rules. Its aristocracy was servile, haughty, and limited in its ability to act.” It took pride in itself as the heir to Greek and Roman culture, but its members never learned how to conduct more modern wars as the Franks and Normans did.

Fifth, Latynina continues, Byzantium was “a quasi-socialist” state in which the government had its hand in almost everything and blocked the emergence of effective markets. There was only one sector in which its anti-market approach didn’t have an impact and that was where it was most needed: economic empires within it that could challenge the state itself.

Sixth, Byzantium was obsessed with “spirituality,” an obsession that led to attacks on groups within the society that left the country in capable of dealing with challenges to it from the outside. When Byzantium faced the rise of Islam, its leaders concluded that the most important task was to root out the Monophysites, something that weakened the state still further.

And seventh – and this is the most striking thing of all – when Byzantium fell, it disappeared without a trace, a fate that has overtaken other empires only when as in the case of the Incas a force from the outside with much more modern military capacity unexpectedly arrives.

Can it be, Latynina asks rhetorically, that Russia’s current rulers really want the country to share the fate of Byzantium? “This is Freud in pure form,” she says, because in trying to mobilize the Russian population, the Kremlin is talking about not the Roman Empire but about a state that failed and wasn’t even able to hold on to its name.

“The high spirituality of the Empire of the Romans, as is well-known, ended when even on the eve of its collapse,” Latynina points out, fanatics from the church and from among the population “did not want to count on the help of the West. Better Islam, they decided, than the West.”

One might observe about Latynina’s parallels between Byzantium and Putin’s Russia what George Kennan once said about the Marquis de Custine’s classic work, “Russia in 1839.” That book may not have been a completely adequate account of the Russia of Nicholas I, but it was, Kennan observed, a very good picture of the Soviet Union of Leonid Brezhnev.