The conflict in southeastern Ukraine is becoming like the Yugoslav war with the Russians and Ukrainians becoming like the Serbs and Croatians, developments which mean that “we cannot now even imagine the consequences” of this war for the region and the world, according to Valeriy Solovey of MGIMO.

In a wide-ranging interview, the outspoken professor nonetheless attempts to describe some of the outlines of this war, only “the beginning stage of which is ending” and which he argues will end with Ukraine’s loss of the Donbas or even more.

Solovey argues that it is correct to call the conflict in southeastern Ukraine a civil war “because citizens of Ukraine are taking part on both sides,” but he adds that Russia’s interference is “obvious to all,” something that should come as no surprise because “external interference is not the exception but the rule of civil wars.”

The conflict is entering a new phase, one in which the scale of military operations, the level of cruelty, and hatred between the sides are all likely to increase. “For Ukraine, the Donbas is already lost morally and psychologically,” because whatever the outcome of the military clash, that region “scarcely can be integrated” into the rest of Ukraine.

“Even if Kyiv will be able to restore formal control over the region,” Solovey continues, there are three reasons to believe that the Donbas will remain apart: a diversionary-terrorist war will continue, the level of hatred between the two nations will be too great, and Russia has an interest in making sure that Ukraine remains off-balance and unstable.

At some point, Kyiv will have to sign a peace agreement recognizing this reality because if it doesn’t, “its territorial, economic and political losses could become still larger.”

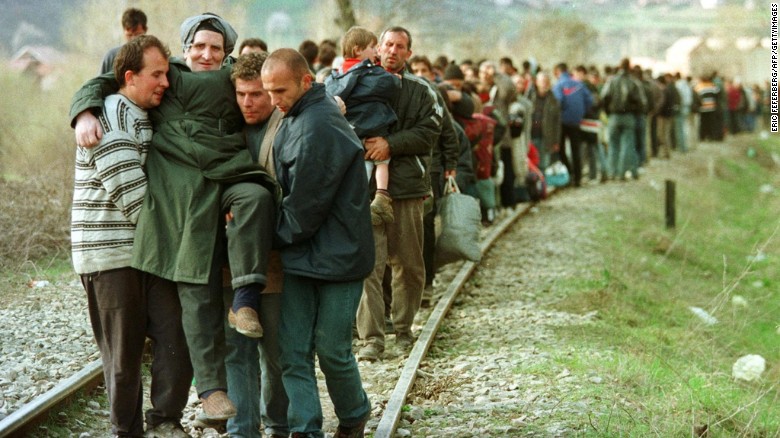

The only precedent in recent European history is the war in the former Yugoslavia, but there is one important difference. In that country, there were long-standing ethnic, religious and cultural-historical divides among the nations involved. In Ukraine, there were “never such dramatic contradictions between Russians and Ukrainians. But now, everything has changed.”

While Russia will continue to interfere, including militarily, the West will not go beyond economic sanctions and military advisors. “And here is why,” Solovey says. A recent NATO discussion concluded that “Russia would be able to occupy the entire Baltic region in two weeks, but NATO could really react only after five, when the game would be up.”

Representatives of the three Baltic states were shocked, he continues. “Why then did we enter NATO if you cannot defend us!” But to defend them or to defend Ukraine would require “a general mobilization” and that would mean World War III. “And no one in the West wants a world war over Ukraine.” Moscow understands this and is acting accordingly.

(Baltic sources say that no such meeting ever occurred. It appears that Solovey is basing his comments on something he heard in Moscow.)

The situation is not like 1914, Solovey says. “No one, not in Europe and not in the US, wants to sacrifice human lives over Ukraine. They don’t even want to help financially very much. One should not exaggerate the significance of Ukraine for the West.”

But if Moscow can act without fear of Western intervention, the events in Ukraine nonetheless carry certain risks for the Russian leadership, and “certain people in Moscow” are beginning to be concerned, although “one should not exaggerate the level of this concern,” as some are inclined to do.

One worry is that Strelkov will succeed too well in the Donbas and his success will lead to the formation of his image as “a victorious military leader,” someone who might exploit that within Russia even if it seems highly improbable just now.

Russia’s annexation of Crimean shocked and angered the West because it showed that Russia was prepared to revise the results of the cold war and that Russia now has “an effective army.” But while angry, no one in the West wants a military conflict with Moscow and many are “openly afraid.”

More than that, the West is even afraid of serious sanctions because Russia is now “so deeply integrated in the European economy, any sanctions would end by hurting the Europeans as well.

Solovey said that he personally “does not exclude” the possibility that “the West would close its eyes even to the introduction of Russian forces.” If the number of casualties goes into “the tens of thousands and the extent of destruction becomes colossal, he says, the introduction of Russian force in Ukraine would be viewed as a peacekeeping mission” at least in Europe.

In the short term, all this is helping to “cement” the current Russian leadership. There are some disagreements, but there is no reason to think that a conspiracy will arise against Vladimir Putin. Over the somewhat longer term, however, Russia’s situation and that of its leaders is anything but enviable.

Among the threats to its stability are “the traditional social-economic problems,” including “in the first instance, the inter-ethnic factor, including the threat of the radicalization of the North Caucasus and also already in the Middle Volga.” That is likely to develop over the next “two or three years.” How well Moscow will cope is an open question.

In addition, there is the growing problem of extremist Islamism among immigrants from Central Asia and the Caucasus, especially since both Saudi Arabia and Qatar are prepared to use them and the Muslim regions for their own purposes, including the spread of their “religious messianism,” against Moscow.

In response to all this, Solovey said, Moscow will continue “to tighten the screws,” adding that he “doesn’t exclude” anything in that regard, including even an explicit rejection of all European values and “the introduction of a simplified system of judicial action regarding political opponents.”

Some in Moscow, he suggests, feel hemmed in even by “the fig leaf of legality,” and they welcome sanctions as a way of deflecting anger about the economic crisis and an occasion for imposing ever-tighter controls. They “prefer a limited ‘iron curtain,’” because they want some advantages of contact with the West for themselves but not for the population.

The Russian population will put up with this if it is introduced gradually rather than all at once, Solovey says. Only a radical shift would cause problems. But the direction in which Russia is moving is disturbing because there isn’t going to be stagnation as some imagine. Shifts of “a truly tectonic character” are coming.