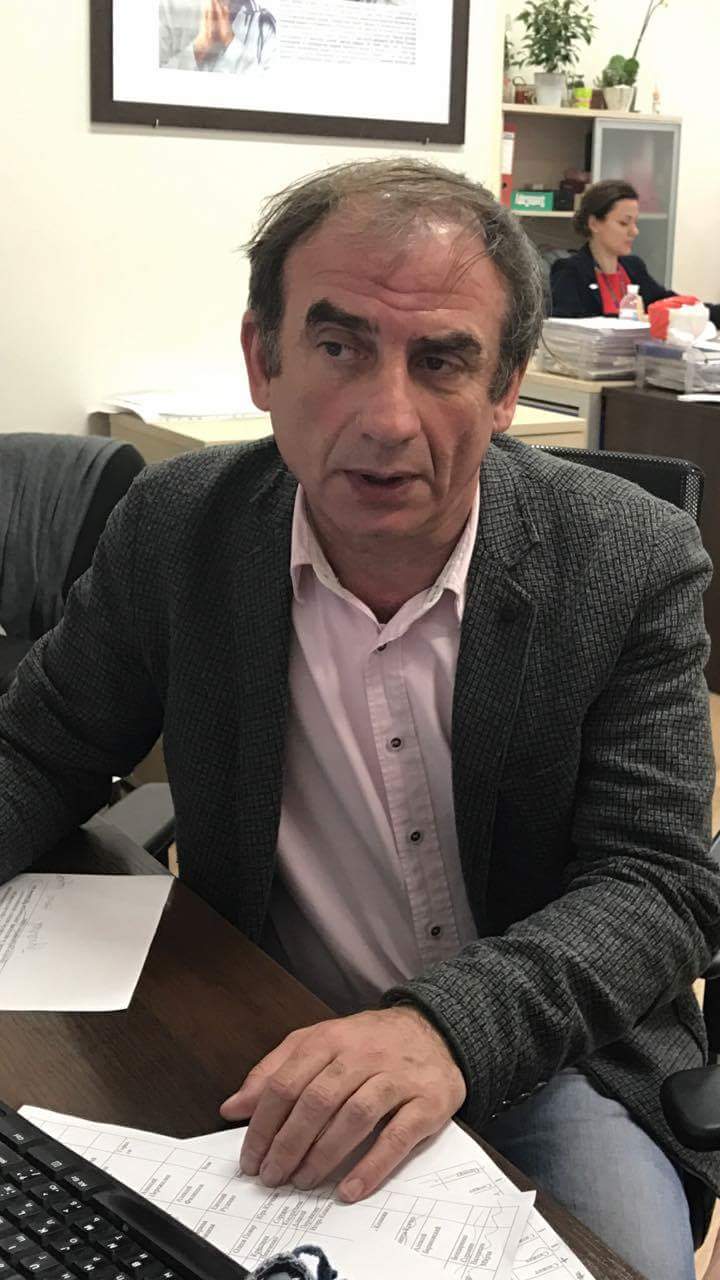

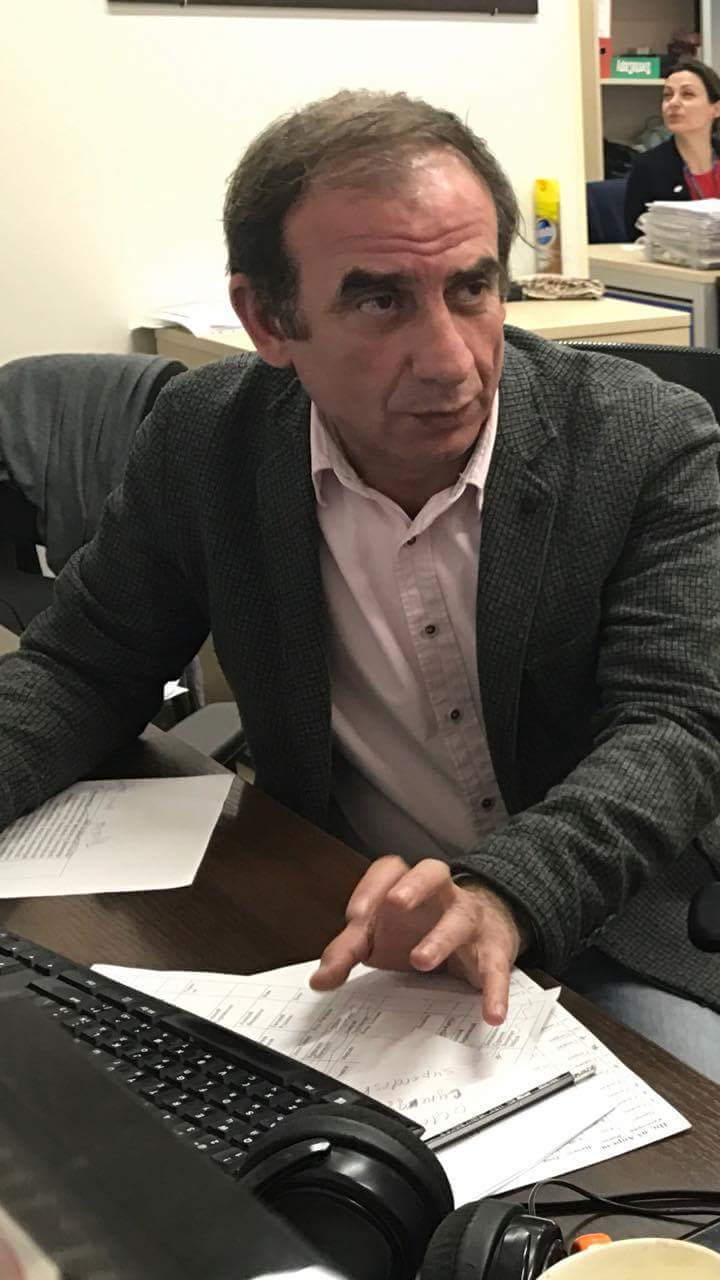

Zurab Kodalashvili is a Georgian-born, UK-based media professional. He used to be the Executive Director at the First Caucasus Channel (PIK) in Tbilisi which was followed by the role of Divisional Director for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) in Prague. Following the Soviet Union’s collapse, he worked on exposing Russian propaganda while cooperating with the most popular world media.

However, before all of that Zurab was an officer of the Soviet Navy and served in Estonia as an assistant of a combat ship at the end of the 1980s. During that period he became disappointed with Soviet and Communist ideas and started organizing anti-Soviet activities in Tallinn with his colleagues. Because of their influence, 11 officers in Estonia left their service in the Soviet Navy.

Having had the experience of being at the regime’s core – its army, Kodalashvili now knows all the glitches of the Russian system, which presents itself as the Soviet Union. He explained to Euromaidan Press why being a Russian spy and Russian journalist abroad is almost the same and told us the details of how Russia controls journalists, why people in the USSR stopped believing Soviet propaganda, and why Russian propaganda is still so powerful.

Being an officer, Zurab started to write for the Russian language newspaper of the People’s Front of Estonia under the pen name Aleksandr Kendal. At the time, Zurab and his two friends who also were lieutenants of the Naval Forces of the USSR became friends with representatives of the Estonian National Independence Party, especially with Valeriy Kalabugin and Sanders Sis, a correspondent of RFE/RL in Estonia. It served as a source of an alternative information for the lieutenants.

Leaving the Navy, Zurab organized the first independent informational agency Iberia in Georgia, got to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, worked for the Russian Service of BBC and later the BBC World and BBC News, started to cooperate with Reuters and France Press.

Kodalashvili studied at the Higher Naval School of Radio Electronics and observed how the Soviet Union tried to send its sailors to western civil ships. In fact, these sailors were spies called to implement Soviet tasks when the “Day X” comes. However, apart from sailors, there were other examples when the regime used civil professions for reconnaissance aims. Basically, all Soviet citizens who left for the West were under KGB surveillance and many of them worked for the KGB, including diplomats, actors, scientists, musicians, and especially journalists.

“The Soviet Union had no access to western countries. So it was stupid to send a real journalist to Great Britain or to the US when you have limited access to it. Of course they would send a spy.”

Zurab emphasizes that now people should also be more careful with Russian business representatives. He gives an example of the founder of the Russian social network Vkontakte Pavel Durov, who in 2013 created the Telegram messenger. Its creators state that this messenger is the most reliable one in terms of security, however, Zurab again doubts this idea. To support his opinion, he says that Dmitry Peskov, the press secretary of the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin, recommended Telegram as the most reliable messenger, which is direct proof that Russian intelligence can use it. Moreover, Durov took $300 mn from Russia, which he also wouldn’t have been able to do without the permission of the Russian government. Among other companies under suspicion are the Kaspersky antivirus and the founder of the fund for investments and the startup investor Maria Drokova who before becoming a businesswoman and receiving a Green Card was a commissar of the pro-Kremlin’s movement “Nashi.”

Also, Kodalashvili gives us a few examples of journalists/spies whom he knew:

“It was a common practice for journalists working in the West to also have been secret service officers. Later, it probably went away. However, after Putin came to power, representatives of intelligence services starting ruling over Russia as a whole. Russia uses information weapons against the West, as well as against its own citizens. Information (or disinformation) is one of the main military tools for Russia. Thinking logically, there is a big probability that the majority of the journalists who work in the West or in Western media are under pressure of the FSB. In my opinion, all of them are. Russian intelligence services were significantly reinforced compared to Soviet times. Now nobody controls them. They rule the whole of Russia.”

Does this apply only to journalists working for Russian state media?

“Not only journalists, but many people in business representations in the West, including those Russians who work in Western think tanks and institutes can end up under FSB pressure. Also among them, there are those Western journalists who have spouses or relatives in Russia,” Kodalashvili says.

To support his statement, Zurab again gives an example of his Georgian friend who is not even a journalist. The friend came to the protest in support of Nadiya Savchenko (at the time, a Ukrainian political prisoner jailed in Russia) and gave an interview to a Georgian TV channel. Zurab’s friend used to live in Moscow for some time and had relatives there. After the friend’s interview, special services came to these relatives. For security reasons Zurab does not reveal the name of his friend but says that such practice is quite common for Russian security services:

“But imagine a correspondent of Radio Liberty or BBC who criticizes Putin and then comes to Moscow where he has a brother, with a wife who has some business. Would not they say: ‘You know what, girl or boy or a great Russian dissident, if you say something, certain things will happen to your relatives.’ Maybe nobody came to such journalists yet, however, I am sure that it will happen in the future. I am not saying that all of them are spies, but all of them are under pressure whether they want it or not.”

How many people are involved in such monitoring?

“I was surprised about that Georgian story. However, in general, doing such monitoring isn’t so complicated. I used to be a representative of western media in Moscow. Supposedly, the foreign media itself was not monitored. However, we received accreditation in the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. There are curators for each country. I think that Great Britain and the US gets more than one because there were a lot of their media accredited in Moscow. However, talking about Russian citizens with interests in Russia who work in Western media, I think the curators are appointed in the same way. For example, whose media is Radio Liberty? The US’s. For sure those who work with them will say: ‘Here is Ivan, Sergey or Petya, he has this business, his mom works there, his wife has this shop. How can we talk to him?’ It’s easy. The main thing is to delegate responsibilities the right way.”

In 2002 Kodalashvili had his own experience of communication with the FSB. The Russian curators of British press representatives tried to coax Zurab into giving a bribe, without success, which left the FSB and police without a reason to arrest the journalist. Then, the security services started threatening to not prolong his press accreditation given by the Russian MFA, as a result of which he would be forced to leave Russia and stop working at the BBC, unless he started cooperating with them.

“For the whole period of my dissidence at the end of the Soviet Union, I fought against the KGB. And now they came again. I was shocked. However, 30 seconds was enough to recover and I started to play a game myself. I understood that I needed to get out of that room. Probably if I would have said that there’s no way I will work with them, they would have provided an alternative option. But I said: ‘This decision will change my life and you want me to answer now? I can’t do this, I need time to think.’ Right after I left, I called a bunch of journalists. My wife hired a lawyer for me. BBC wrote a letter to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I told them through my acquaintances that if they’ll pressure me I’ll go public, that I won’t give up or react to provocations. And the case was archived, but not closed. In 2002, it was possible to go public with such a story. Now, this is hardly possible, as the entire press is controlled by the security services.”

Can you comment on the case of Roman Sushchenko, the Ukrainian journalist who came to Moscow for a private visit and was arrested under the accusation of espionage? He was a Ukrainian correspondent in France. Do you mean to say that this is absurd for Ukrainians, but an ordinary thing for Russians?

“Yes, for them it is not absurd. If we take into consideration that for them any journalist who works in a western country for sure has to be a spy, according to their logic Sushchenko is also a spy. It’s the usual Kremlin logic. I am confident that they are confident he is a spy.”

Read also: Ukrainian journalist Roman Sushchenko celebrates birthday in Putin’s prison

But Sushchenko is not alone there. There are several political prisoners who were accused of espionage.

“Political prisoners are another topic. Anyone can be accused of espionage. But if talking about a journalist accused of espionage – it totally fits into the FSB’s reasoning. An agent would say: ‘If I send people to France or England [journalists to work as spies] then how is Ukraine different?’.”

Why do you think people in the Soviet Union stopped believing propaganda? And why do they believe it in Russia nowadays, having had the experience of Soviet propaganda?

“People in the USSR started to feel and to see something beyond their Soviet reality. Many of those who used to work at Radio Liberty, old veteran dissidents, those who were sitting in Munich or Washington, at The Voice of America, BBC, were saying ‘We destroyed the Soviet Union, we are cool.’ Maybe they destroyed a small piece of it. However, the strongest blow came from the emergence of the opportunity to see another world. You can tell a lot, but watching it from a video player is different. I think that the Japanese corporation JVC which was a pioneer in creating video players gave the communist system a mortal blow. The Soviet people started not only to listen to ‘voices.’ Who listened to them? Dissidents. Now common citizens started to watch an action film about Rambo, or just about beautiful life in Florida or California, or even porn. They saw a totally different world. People who never ever thought about dissidents and how ugly the Communist party was watched the videos. I think this is the main reason why the Soviet people changed their minds.”

So Putin was right when destroyed NTV and ORT [Russian channels thanks to which freedom of speech existed in Russia in the 1990’s]?

“From the point of view of KGB, of course. However, now even without NTV anyone who, for example, wants to know news from Ukraine can find them in Ukrainian sources.”

Why don’t Russians use these Ukrainian outlets?

“When we were running the channel PIK, and I was its CEO, the first thing I did was forbid my employees from criticizing any nation, first of all, the Russians, on air. That is why many people who considered themselves Georgian patriots felt abused. I told them: ‘Guys, we are broadcast in Russia. If we abuse them on air, nobody will watch us.’ I forbade abusing any nation: Ossetians, Abkhazians, Armenians, not only from the ideological point of view but also from the common to all mankind point of view.

But what did Putin and his media do first of all? They turned Russian citizens into accessories of all the sins and ugly things which Putin and the chekists have done. When they do something, they say ‘It’s us, Russians.’ It was drilled into the Russians’ minds that bullying Putin means bullying Russia and that every Russian is attacked in criticism of Putin. Because ‘Putin is Russia, Russia is Putin.’ And it is drilled into their minds 24 hours a day through TV, radio, and newspapers. One body. So Russians are constantly in a defensive position. They really associate attacks on Putin with Russian interests in Syria. They worry about Assad because he is also ‘ours’ already. They are confident that any crimes of Putin are committed by ‘us’ and in ‘our’ interest.”

But at the same time, they see videos with the same beautiful life in Florida… What can be done?

“The West does not want to realize that Russia has already been in a state of war for a long time. They fight psychologically. They know that the West is bad. They can go there for a vacation, they can spoil something there, saying: ‘Yes they have good clothes and food, so what? We will rest there and then we will come back and defend our country. They will attack. They want to take away our land, our gas, our oil.’ It is turning the population into zombies.”

What should Europe and the US do in this regard?

“The advice is to take their heads out of the sand, to stop pretending they are ostriches and understand that Russia is at war against them. When they realize it, they will know what to do.”

So how exactly should the West work with the minds of Russians? Should it pay some special attention to it?

“For sure. The majority of Russians there [in the West] are affected by Russian propaganda. It is a bomb waiting to explode.”

Would it be enough to create a competitive product which would dislodge this Russian propaganda or should it be just suppressed?

“To create a competitive product and to suppress simultaneously. Because Russian state media is not media. It is a weapon of mass destruction.”

So censorship is needed?

“This is not censorship. How can censorship be applied to weapons of mass destruction? The word ‘censorship’ can be applied to media, but they are not media, they do not produce journalism. They are weapons.”