A state in decline is a dangerous thing. An autocrat in decline is even more so. Putin’s provocations have caught the West off-balance for too long, resulting in a series of provocations in Putin’s confrontation with the West. The Biden administration’s new sanctions, and undisclosed measures, are welcome, but the West needs to move beyond sanctions, from reactive responses to more preemptive measures.

Putin’s game

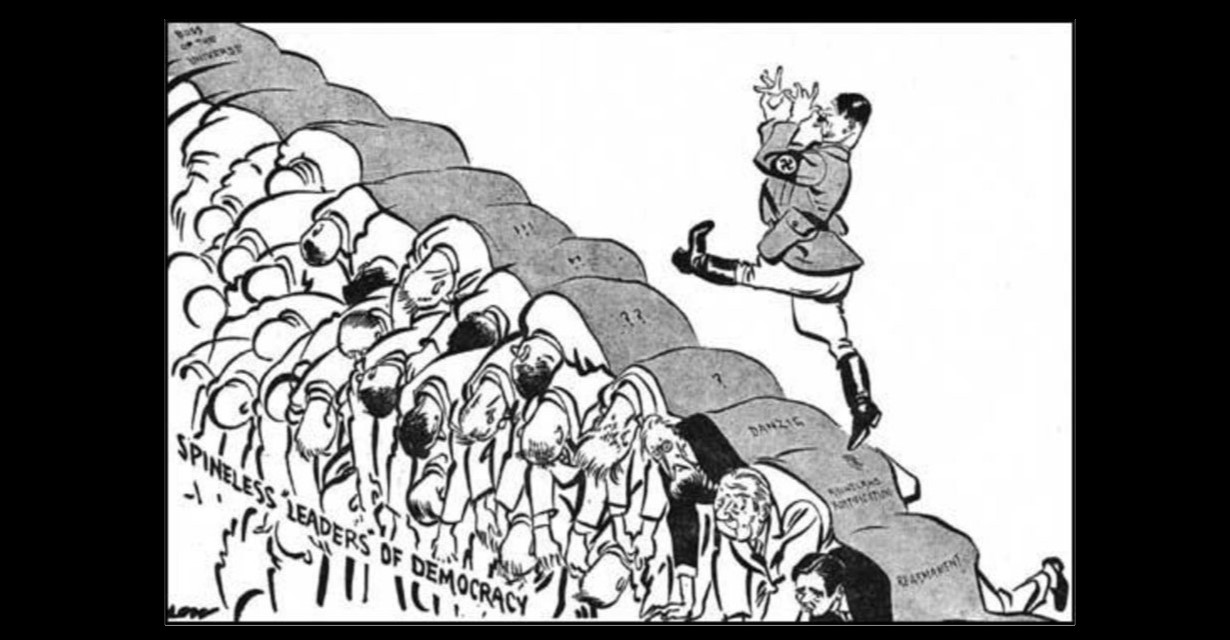

Putin’s deft approach to staging provocations has time and again given him the initiative against the West. He has moved incrementally, struck unexpectedly, and paused just short of drawing a serious response from the West. Fortune has favored the bold, as they say, but it is time the West learned to be bold as well. Otherwise, Putin’s latest military escalation in Ukraine or some other provocation will spin out of control.

Putin benefited from the element of surprise. His boldness surprised everyone when he seized Crimea. Unwilling or unable to confront this aggression, Ukraine and the West failed to act forcefully, even when Putin cemented his victory by incorporating Crimea into Russia proper. The West then struggled to confront Putin’s barely disguised invasion of eastern Ukraine.

At the same time, Putin was not reckless. In eastern Ukraine, after initial military success in Donbas and Luhansk, Putin carved out two anti-government enclaves. However, when Ukrainian resistance proved more resilient than he expected, he gave up on a new Novorossiya across southern Ukraine before the West could escalate its response.

Where he has failed, he has retreated–not always elegantly–while salvaging what he could.

When Russian missiles shot down commercial flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine, killing 298 persons on board, Putin was clearly shaken but refused to accept responsibility, and Russian disinformation kicked into overdrive, offering multiple, contradictory explanations for the tragedy, which were easily dismissed as having no grounding in reality. Although not credible, the disinformation succeeded in muddying the information sphere and Russia has so far avoided accountability.

Similarly, Putin’s denial of a campaign of murder against Russian critics in Russia and in the West, including Britain and Germany, is not credible, but the campaign has so far been carried out without spurring the West to respond forcefully enough to prevent Putin acting again where and when he chooses.

Although Putin’s successes fall short of gaining control of Ukraine or neutralizing the West, his incremental gains are, nevertheless, effective from Putin’s point of view because they constantly reset the baseline in Russia’s favor when negotiating with the West.

Instead of forcing Russia to vacate eastern Ukraine or to return Crimea, the West’s limited responses have stabilized the situation rather than rectified it. Seven years after Russia shot down flight MH17 over Ukraine, Russia still has not been held accountable for the shooting (although the ongoing trial in the Netherlands has exposed abundant evidence of Russia’s culpability and may finally bring Russia to account). Tangible gains and relatively low costs have encouraged Putin to continue his provocations.

The recent massive increase in Russian military personnel and hardware on Ukraine’s border is a threat built upon previous successes. How far is Putin prepared to go? Does Putin intend to formalize Russia’s occupation of eastern Ukraine? Does he plan to open a corridor to Crimea to relieve a severe water shortage there? Or, is he just signaling to the new US administration that he will respond aggressively to any attempt to reign in Russia’s foreign policy? Would any of these options draw a greater Western response than in the past? Would a significant Western response after the fact have a greater impact on Putin’s future behavior than in the past?

Rebuilding the empire

Given the uncertainty of Putin’s intentions, what is Putin’s game that the West should be concerned with? The sum of Putin’s provocations points to Putin not wishing just incremental gains but to rebuild Russia’s empire and elevate Russia’s importance on the global stage. Putin does not just wish it, he is prepared to make it happen. Recent provocations, including those in Ukraine and interference in the US’s domestic affairs, go far beyond the conflict in Ukraine.

Short of actual war to demonstrate Russia’s power and to defend Russia, as Putin believes, from Western aggression, Putin wants to discredit the West by demonstrating that NATO will fail to defend its members and that Western society is in decline, which would give Putin a free hand in Ukraine and throughout Eastern Europe from the Baltics to the Caucasus. Conflict in Ukraine is a first step.

Putin–like another autocrat, China’s President Xi Jinping–genuinely believes the West is in decline. It doesn’t matter if he is wrong. His actions are predicated on this belief. He looks at civil strife in the West and believes it is symptomatic of collapse, as it has been repeatedly in Russia.

Putin is prepared for victory when the collapse arrives. He has funneled resources to the military at the expense of civil society. He relies on cyber warfare and disinformation to lessen his opponents’ resolve and mitigate Russian weaknesses in areas he cannot overcome. He has built financial resilience by limiting government debt, purchasing gold as a reserve, and reducing the US dollar share of Russia’s reserves. He is working with China to build an alternative to SWIFT. And, he has prepared his political future by changing the constitution to allow him to continue as president for as long as it takes for Russia to reemerge as a global power. And if he can do it before the West resolves to act, he can do it relatively easily.

The West is stronger than Putin believes

However, Putin misunderstands the West. A particular vulnerability is that Putin and his coterie get the West’s weaknesses but they incorrectly assess their significance. Social inequality is pervasive but Western society is fluid and has outlets for dissent–the US and the West are going through a painful recalibration of equity in society in response to changing demographics and economic opportunity, not in response to Russian provocations.

What should concern Putin is not the West’s demise but Russia’s. Putin has increased Russia’s social fragility by criminalizing dissent and restricting civil society freedoms, often using old Soviet tropes such as labeling anyone in contact with the West as a foreign agent.

Similarly, corruption appears endemic in the Western elite with multiple scandals, including the ease with which Western elites can be corrupted through money laundering from Russia and elsewhere. Money laundering and influence buying will be arguably harder though with new transparency laws in the EU and the US, and corrupt actors will be more often exposed by a more alert civil society and free press that have grown more aware of the scope of corruption.

Even the UK’s departure from the EU, while cause for Kremlin celebration, was a tale foretold. Its accession to the EU was always conditional, as reflected in its failure to adopt the Euro. The UK’s departure says more about the UK’s circumstances than the EU’s.

Meanwhile, the EU is more resilient than widely recognized. For example, the latest World Economic Outlook projects EU economic growth in 2021 at 4.4%, while Russia is expected to grow at a still respectable but slower 3.8% (the US is projected to grow 6.4%). The latest Eurostat figures for trade, although lower than a year ago due to COVID, show that the EU trade surplus in goods with the rest of the world grew by EUR21.1bn from a year ago. Intra-EU trade remained almost unchanged during the pandemic. Waiting for the EU to collapse may take a very long time while the Eurozone grows faster than Russia. Although it often seems to barely muddle along, for the most part, the EU’s bureaucratic reconciliation processes serve to respect the voices of all its members, giving the EU added resilience.

There is also the matter of Putin’s personality. His pugnacious, St. Petersburg mean streets persona, although seemingly popular with the Russian man-in-the-street, has worn thin in the West that sees little room to find common ground on issues of mutual concern. Putin’s shame at the collapse of the Soviet Union fuels his sense of Western injustice–the longer Russia takes to reassert its importance, the more aggrieved Putin becomes and the less accommodative.

The need for a preemptive strategy

President Biden’s new sanctions, and undisclosed measures, for Russia’s interfering in the 2020 presidential election and for the so-called SolarWinds hack, as well as the authority to introduce more sanctions laid out in his executive order of April 15, have the merit of being broad and targeting the Russian financial system, which will get the Kremlin’s attention.

However, the West needs more than a new, more proactive strategy against Russian aggression, it needs a preemptive one. Redlines won’t work. President Biden’s new sanctions are welcome but look similar to past sanctions that did not prevent further provocations. Putin cares little about sanctions against Russian individuals or entities. Even the new financial sector sanctions do little harm and signal only the intent to become more serious. Moreover, that Biden has offered a summit with Putin to discuss cooperation on mutual interests sounds distressingly like a reset, which has failed multiple times before.

This leaves the West’s responses reactive–weighing in after the fact. That posture has proven ineffective in preventing Putin from staging further provocations.

Above all, the West needs to recognize the scale of the threat. Ukraine is the immediate battleground, both for Ukraine’s future and as a test of Western resolve against persistent, expansive Russian aggression that will not diminish until Putin’s threat to the West is eliminated–not because the West threatens Russia, but because Putin is a tangible threat to the West.

Next, the West needs to coordinate better in advance of Putin’s next provocation so that when unconventional threats emerge–such as Putin’s radioactive and chemical poisonings in London and Salisbury of his opponents–there is an effective, coordinated response along the lines, to her credit, of former British Prime Minister Teresa May’s response to the Salisbury poisoning. The response to the 2006 London poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko that took ten years for an independent inquiry to point the finger at Putin was objectively inadequate.

Measures that are more effective than sanctions are needed. If it was known that the St. Petersburg troll factory was spreading disinformation and attacking Western democratic institutions, it should have been shut down, not just exposed, by whatever creative means the West had at its disposal. Sanctioning the sponsor of the troll factory in Putin’s circle is not dissuasive enough. If the evidence pointed to Russia having shot down flight MH17, Russia should have faced an international court in a timely manner up to and including the highest Russian authority responsible for that act of terrorism, which would have gone all the way up to Putin.

The West should fix its blindspots, principally money laundering and influence buying. It has gone some distance in doing this but, for example, a former German chancellor should not be serving as chairman of the Russian energy company, Rosneft, not because Gerhard Schroeder can’t pursue his private economic interests, but because Rosneft has been shown time and again to be a political actor for the Russian state, which means it is a vehicle for influence peddling and building legitimacy for Russia’s political projects, such as Nordstream2.

The West should bolster its frontline allies. Ukraine’s domestic weaknesses threaten its ability to defend itself from Russian aggression. It needs judiciary reform and anti-corruption support to curb oligarch interference in the government and the economy, and it needs economic support to improve social welfare. Ukraine also needs substantial military support, including anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles, which the Ukrainians need to blunt a Russian invasion even if the Ukrainians fight bravely, and they will.

Moreover, the West needs to support threatened communities–in eastern Ukraine, Syria, Libya, and Armenia because instability radiates outward and serves Russia’s interest by opening another front in Russia’s war on Western values and institutions.

Carl Bilt, former Prime Minister of Sweden, has long experience with Russia in Ukraine. He describes in a recent Washington Post op-ed the West’s posture regarding the recent Russian military buildup in Ukraine as one of “confusion and nervousness.”. It is time for the West to resolve to confront Putin’s aggression. If not now, at a time of Putin’s choosing, he will attempt to correct history and reincorporate Ukraine into a new Russian empire as part of a larger attempt to counterbalance the West.

The West needs to act to prevent Putin’s designs because it has no choice. An aging autocrat’s predisposition to resentment, impulse to strike out, and illusions of grandeur, point to ever-increasing risk and a higher cost from miscalculation. A state in decline is a dangerous thing. An autocrat in decline is even more so.