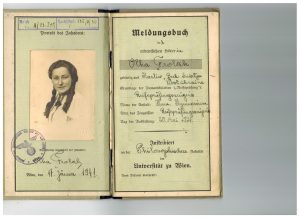

Our mother was born in a family of eight children in the village of Karliw (present-day Prutivka), Sniatynsky Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast on December 26, 1919.

As a young Ukrainian student and political activist, she was arrested on December 11, 1943, imprisoned in Wels/Donau and Linz Gestapo prisons, and then incarcerated in Ravensbrück concentration camp (acknowledged period of detention – from December 11, 1943 to April 5, 1945).

This is her story…

On September 21, 1939, the Red Army (part of the forces which had invaded on September 17, under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) took over the city of Lviv. In October 1939, our mother Olha enrolled at the Faculty of Mathematics, Ivan Franko University in Lviv. At the beginning of December 1939, a group of student activists toppled and destroyed the statue of Lenin which stood in the university courtyard. The NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) began rounding up Ukrainian students and activists.

With the help of the Ukrainian Aid Committee (Український Допомоговий Комітет), Olha fled to Krakow, Poland, where she was registered in a Ukrainian refugee camp. She was awarded a stipend to continue her studies and travelled to Vienna, where in 1940 she enrolled at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Vienna.

The year was 1943… Almost every inhabitant of Ukraine knew that Hitler’s Third Reich was losing the war. Instigated by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), frequent attacks on retreating German troops intensified all over occupied Ukraine. The German Wehrmacht began retreating to the West with heavy casualties.

In the ensuing chaos, Hitler’s Ubermenschen (ideal superior human beings) began arresting and executing Ukrainian activists in Ukraine and those who had fled to the West.

In July 1942, my life took a new turn… Ivan and I got married, not in Lviv, but in the village of Liubyntsi, north of Stryy, where our uncle, Reverend Vasyl, served as parish priest. My husband Ivan had been ordered by UPA headquarters to go north. Our paths diverged…

In 1943, the Gestapo began carrying out mass arrests of Ukrainian activists, including students in Germany and Austria. In December 1943, hundreds of Ukrainian students were rounded up in Vienna. In the early hours of December 11, the Gestapo broke into my room, thoroughly searched through my affairs and transported me by train to an old prison in Wels, near Linz.

It is not easy to write about the difficulties and unbearable conditions that I experienced in Nazi prisons and in Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany. Today, I can still remember the brutal faces of the Gestapo officers leaning over me during the interrogations in Wels prison. The truncheon raised high above my head; my trembling arms shielding my naked head from the vicious blows; their harsh cries echoing in my ears: “Hande weg! Du Schweinedreck!” (Hands away! You filthy pig!). My arms drop listlessly; the throbbing pain in my battered head numbs all logic and thought. Suddenly, the truncheon falls so heavily on my head and chest that blood gushes forth and pours down my blouse.

“Genug!” (Enough!) shouts the second Gestapo officer and orders the guards to return me to the prison cell. The cell was small, dark with a tiny grated window; no bench, no straw mattress, just an old, dirty, tattered blanket on the cold cement floor. A slop-bucket and a small bowl stood in the corner. The heavy iron door banged shut. I found myself lying on the cement floor; my face felt hot, painful and bruised. I laid my throbbing, aching head on the stone floor, seeking relief on the cool, damp cement; the blood continued to seep from my chest. I lay there for hours, but could not fall asleep due to the shrill cries of the Gestapo and the wailing of prisoners coming from the neighbouring cells.

The interrogations continued relentlessly – all week, day and night. The moaning subsided; moments of brief silence were interrupted by cries of pain. “Los, los! Aufstehen!” (Come on! Come on! Get up!). I stood up and dragged myself once again into my cell to embrace the cold cement.

Finally, they transported me to the prison in Linz, where I was placed in solitary confinement for a week. Next, I was transferred to a larger prison cell occupied by five French and two Czech women. Wooden bunk beds, tattered blankets and straw-filled mattresses; strict imposition of prison rules that no one dared question…

A tiny “parasha” (slop-bucket) for so many people; the stench of human excrement was unbearable. We took turns washing the floor and cleaning this “receptacle”. The prison guards checked our work regularly as we stood in a row, immobile and trembling with fear. Very often they would glance at us and bark sarcastically: “Nieder! Sauber machen!” (Get down! Clean it again!). And we would drop quickly to our knees and begin scrubbing again.

I became feverish, started hallucinating at night, my stomach refused to accept any food. My prison mates took turns sitting with me at night to prevent me from falling off the bunk bed. The guards were indifferent to my illness. For three days, the blood spurted from my nose and right ear, and then thick pus began oozing from my ear. I lost consciousness…

I awoke in the prison infirmary. A small room, with a tiny grated window, a sturdy door with a viewing window. Finally, the so-called “doctor” appeared, gave me an injection, and took me to another room where two “assistant nurses” cleaned my ear… with no anesthesia, just a local analgesic. They began working brutally on the mastoid bone. I fainted again; I dreamt I was back in the interrogation room and the Gestapo officer was bludgeoning me mercilessly about the face and head. I woke up in the “hospital cell”. My mouth tasted of blood, my hands were tied to the bed, my sore head was tightly bandaged. After a few days, they transferred me back to my cell. My prison mates wept when they saw me as they believed that they would never see me again.

In the second half of June 1944, we were herded into freight wagons and transported to Ravensbrück concentration camp. The train travelled slowly, as frequent raids by Allied aircraft had destroyed many railway tracks. During our stop in Salzburg, I saw many prisoners and students from Vienna in the prison yard, but was not able to speak to them. The students and others were waiting for transport to Dachau concentration camp.

Our train suddenly turned back to Linz because the railroad tracks to Ravensbrück had been bombed.

After a few days, the freight wagons filled with women prisoners were again moving towards Ravensbrück. My head was still bandaged to protect the throbbing wound; the bandage was no longer white but grey from the dirt and oozing pus. The wagons were so overcrowded with girls, young and elderly women that there was no room to sit… and one could but dream of lying down.

The human mass swayed with the rhythm of the train – hungry, thirsty, sluggish and moaning in despair!

From time to time, the train stopped, the doors opened, the guards threw a few pieces of black, half-rancid bread and handed us some watery, black coffee. They shouted orders loudly, the dogs barked incessantly… the noise was so deafening that it drowned out the wailing and moaning of prisoners. One of the German guards – a brutal, ferocious beast – stood in our wagon, kicking prisoners who happened to be nearby. Cries of pain echoed throughout the compartment. The German scourge had fallen upon us. None of the prisoners dared move. We turned to stone, silent and terrified…

After many long, dark nights, interrupted by Allied aircraft attacks, the train finally reached Prague. The prisoners jumped out of the wagons, fell to the ground from exhaustion, crowding together as the Gestapo screamed hysterically: “Los, los! Schneller!” (Come on! Come on! Faster!). We stumbled along until we reached a large prison yard filled with hundreds of women waiting for transport. It was a pitiful sight. Young and elderly women crowded around a huge cauldron, waiting for their meager rations. Suddenly, I heard someone speaking Ukrainian. I was overjoyed. I approached them slowly. We spoke quietly. They were from Poltava Oblast (there were about 80 women), who had been taken to Germany by force and imprisoned for different reasons.

I was fortunate enough to spend my time in Ravensbrück concentration camp with these wonderful women. Despite our dire situation, they continued to joke, believing that everything would turn out all right. Two good, particularly helpful friends – Liudmyla Nechypor and Nadiya Romaniw from Poltava Oblast – were tortured to death in Ravensbrück in August 1944. Their wish, which they repeated incessantly day after day, was never fulfilled: “We must stay on our feet. We mustn’t fall, because those dogs will soon be gone! And, we’ll return home.”

This convoy of exhausted humanity arrived at the camp in July 1944. It was then that we saw them… the kapos, lords and masters who brutally forced prisoners to do their bidding (kapos were inmates of Nazi death camps who were appointed as guards to oversee prisoners in various tasks). They were mostly hardened criminals, with years of experience. They drove the new arrivals into the bathing area. They took away all our possessions, stripped us naked, and herded us into a cold shower. Each of us received a long blue-and-white striped uniform with a large black number on the back. A red triangle (for political prisoners) with the same number was emblazoned on the uniform, just above my right breast. We also received wooden clogs.

I became “Häftling-49061” (Prisoner No.49061). This number – 49061 – was now me, my person. At each roll call, I had to shout it out, loudly and clearly.

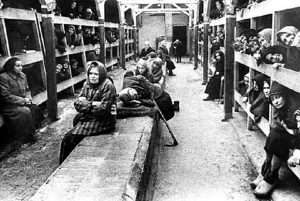

The kapo took us to the barrack, where we were each assigned a bunk bed. Two inmates were forced to share one bed. What joy, what surprise, when I discovered that my bed companion would be an older Ukrainian woman – Teodoziya Hayvas! Each bed structure consisted of three levels; our bunk was at the top, almost near the roof. The older prisoners occupied the lower bunks, the younger women got the higher ones. I learned that there were several elderly Ukrainian women in the same barrack. One of them was Oleksandra Hnatkivska, whose daughter Dariya “Oda” Hnatkivska Lebed (wife of Mykola Lebed), had been placed in solitary confinement with her infant daughter*. (*Zoya Lebed, the youngest Ukrainian prisoner incarcerated in Ravensbruck)

Other barracks housed Ukrainian students from Berlin, Vienna and Lviv (Lida Ukarma, Olenka Vityk, Darka Sydir, Mariyka Orenchuk, Anna Khorkava…). With time, I learnt that the mother and wife of Yaroslav Hayvas, Oleksandra Hnatkivska’s sister Mariya Hryhortsiv and her daughter Vaya were also held at Ravensbruck.

The bunk was so narrow that my bed companion and I had to turn over at the same time, while the tiny insects that nested in our mattress and blanket gave us not a moment of reprieve. No matter how often we searched and destroyed them, we were not able to rid our cot of their presence. A strong, foul stench emanating from the human mass pervaded the air under the rooftop. There were 150 to 180 prisoners in our barrack. The long, long rows of barracks, each crowded with female prisoners, stretched across the territory of the camp. There were Ukrainians from the eastern and western regions of Ukraine, Czechs, French women, Germans, Poles, Hungarian Jews, Belgians, women from all the countries where the Gestapo boots had trampled over the land.

All newly-arrived prisoners went through a medical examination. Each inmate had to strip naked and proceed barefoot before the medical commission. The younger inmates were selected to work in the Siemens factories, which were hidden by thick foliage near the concentration camp. I was assigned to this work. Every morning at 4 o’clock, the kapo blew her whistle, rousing all the women to appear immediately before their barrack for roll call. We stood in rows, shivering in the freezing cold, our feet numbed by the cold and snow. We waited for our numbers to be called and for the Lagerälteste (senior camp inmate) to announce the result to the commandant. Weak, emaciated bodies that could no longer stand upright, often fell to the wet, muddy ground. At that moment, the kapo would drag the poor feeble woman forward and leave her to her fate. The roll calls were one of the cruelest ways of punishing the prisoners.

The shrill whistle signaled that the Arbeits Kommando (work team) was ready to march toward the factory and start a new day of interminable labour.

And so, day after day, this mad Gestapo tango continued, pushing many inmates over the edge of despair and to death. Every day, dead bodies were removed from the barracks, taken down from the electric barbed wire fence, dragged from the infirmary – some still alive, but barely breathing – and dispatched to the crematorium.

When I finally saw the sun of freedom, my body had become blue and swollen, my face was covered with a mossy substance, and I weighed not more than 45 kg. Leaving the camp, the words of my tortured inmate-friends resounded in my ears: “We must stay on our feet. We mustn’t fall… we will return home.”

As we turned our heads toward the sky, the bright rays of the sun – and freedom – warmed the skeletal bodies of my inmate-friends and the moving mass of gaunt and lifeless women.

In the chaos that reigned over Europe in the last months of the war, a group of Ukrainian women that included our mother was discharged from Ravensbruck and sent to Luben/bei Liegnitz detention centre under the escort of the Gestapo. When the German Army surrendered in May 1945, our mother was transferred to Augsburg, and then she made her way to Munich, where she was reunited with our father Ivan.

On September 28, 1948, our mother Olha, with her husband Ivan and their baby daughter Khrystyna arrived in the city of Québec, Canada aboard the S.S. Samaria.

Olha Froliak-Eliashevska

Prisoner No.49061

Ravensbrück concentration camp for women

Video about Ravensbrück concentration camp for women by Chronohistory (32 min)