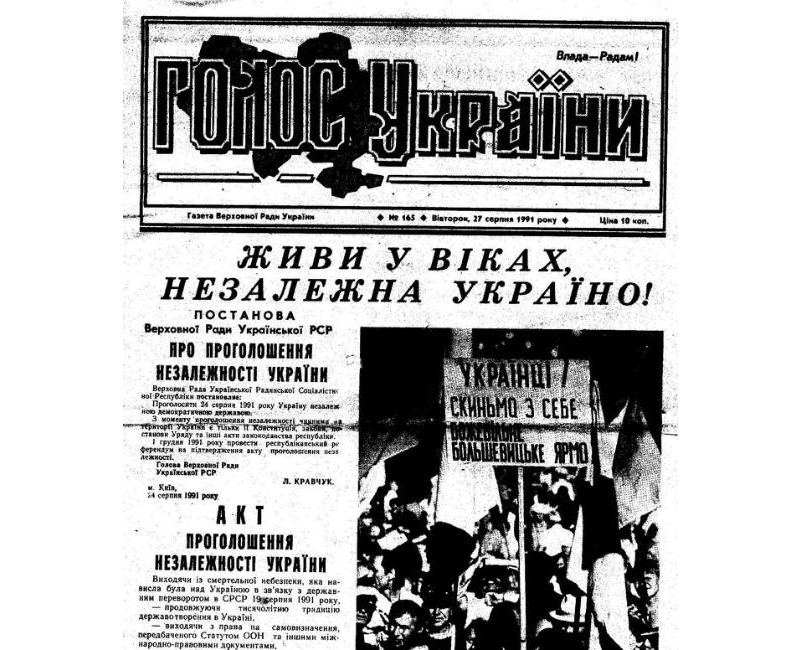

There “cannot be a more bitter date for contemporary Russia than August 24, 1991,” Yevgeny Ikhlov says, when Ukraine proclaimed its independence and thus showed the bankruptcy of all three Muscovite imperial projects: the Orthodox Third Rome, a European Russian Empire, and “’the new historical community of the Soviet people.’”

In a commentary on the Kasparov.ru portal, the Russian analyst says that this becomes clear if one imagines for a minute that Ukraine had not declared its independence but instead had somehow agreed to remain in a Soviet Union “with legitimate President Gorbachev.”

Had that been the case, he points out, the renewed USSR would have had only “two union sovereign republics, the Russian SFSR and the Ukrainian SSR,” and the two would, according to the April 23, 1991, decision of the USSR Supreme Soviet made their respective autonomies “sovereign.”

Under these conditions, “the Ukrainian SSR would have lost Crimea, but the RSFSR would have lost the North Caucasus, half of the Volga-Urals region, and also the Khanty-Mansiisk and Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Districts and Yakutia-Sakha.” Yeltsin’s Muscovy would have been left “without oil, gas or diamonds.”

“It would be a good thing,” Ikhlov suggests, to ask those who are nostalgic for an empire of the Russians whether they would want to live in union with Ukraine under the power of Gorbachev (or his successors from the Central Committee) but with new borders for their own union republic along the Terek and Volga.”

The answers would be self-evident were such people thinking, but they remain prisoners of the kind of passions that led the Israelites to protest against Moses who led them out of Egypt because while in the desert, they remembered that in Egypt and even in Egypt’s jails, they were given food.

Given that, Ikhlov continues, the departure of Ukraine is an even greater tragedy for these Russians, Ikhlov says, because it highlights the bankruptcies of the three major Russian imperial projects of the last millennium.

At the end of its existence, the first of these projects, which one can call the Third Rome, received “an enormous gift: its vassal became the Hetmanshchina, a significant portion of the former Russian Lithuania along with Kyiv. That had the effect of convincing Russians that they had a single Orthodox civilization that was “an alternative” to the West.

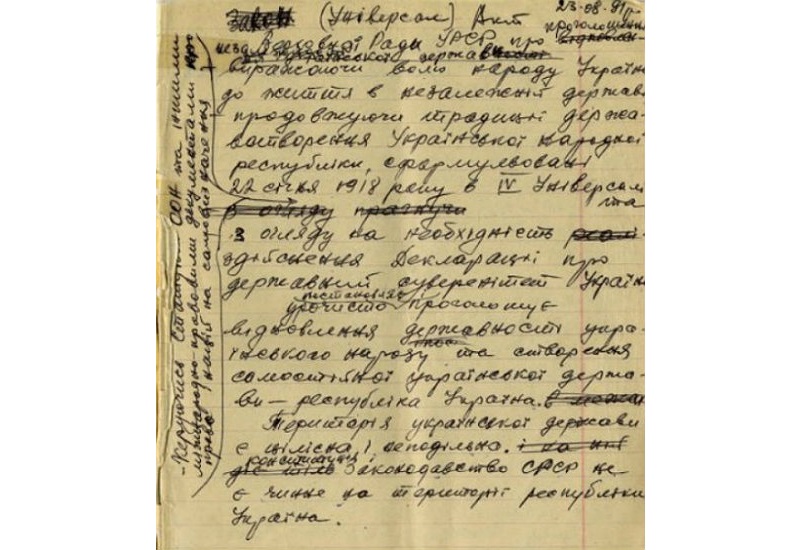

“Ukrainian independence in 1991 is a recognition of the historical bankruptcy” of this notion, Ikhlov says.

The second Russian imperial project was that of Russia as “a joint project of Russians and Ukrainians for the establishment of a European empire as hegemon over the Baltics,” one that resembled in some ways the British Empire as “a joint project of the Anglo-Saxons and the Scots.”

“Ukrainian independence in 1991 is a recognition of the historical bankruptcy of the project of the European Russian Empire,” he argues.

And the third Russian imperial project, that of the USSR with its Russification, depriving of the Ukrainians of their own identity and with its insistence that Ukrainians be prepared to always be “’the younger brother’” also continues to animate many Russians, Ikhlov suggests.

But “Ukrainian independence in 1991 is a recognition of the historical bankruptcy of the project of ‘the new historical community of the Soviet people.’”

It is thus no wonder that Russians find it so hard to accept the idea of Ukrainian independence and at the same time why Ukrainian independence is so important to the possibility, however small, that the Muscovite state and its Russians can overcome their imperial dreams.

Related:

- How Russians see Ukraine’s independence

- Putin regime has long had an ideology – Great Power Imperialism — Pavlova says

- Kerch bridge emblematic of new Russian imperialism, Kazarin says

- Moscow’s pursuit of imperial greatness may end up with disintegration of Russia, Rubtsov says

- Rabid Russian imperialism and anti-Americanism feed worldview of key Kremlin strategist

- Response to imperialist video “I am a Russian occupant” challenges Kremlin’s selective history

- New “old” Russian imperialism and hybrid wars — an historical overview