“Have you seen The Shawshank Redemption? This is a similar story, but this one is true!” says Alim Aliyev, founder of KrymSOS.

One summer morning, Sofiya, an employee of KrymSOS in Lviv, came to work and saw a thin young man sitting at the door of the office. This was nothing new as Crimeans knock on the door almost daily, but this man’s story is like a Hollywood film script that is hard to believe.

It was Yuriy Ilchenko, the Sevastopol blogger, but he could not be sitting here, at the door, as he had been placed under house arrest in Crimea.

THE PARENTS

When the Ilchenko family refused to accept Russian citizenship, they were issued certificates No1, 2 and 3 because they were the first to do so.

Yuriy Ilchenko was arrested by Russian security forces in Crimea on July 2, 2015. The FSB branded him a “terrorist” after the Crimean blogger had posted an article expressing his opinion on the annexation of Crimea by Russia.

We met the family first in Novooleksiyivka, a town on the border of Kherson Oblast and Crimea, a few hours after Yuriy’s parents had successfully crossed into mainland Ukraine. Hennnadiy Malov, Yuriy’s father, shakes his head and speaks quietly:

“We’ve escaped from a land of fear. I still can’t believe we’re safe and have nothing to be afraid of, that someone will knock on our door and take us away at night. (Ilchenko is the name of Yuriy’s mother-Ed.) The regime hasn’t changed at all…in 1937, they shot my father-in-law, and now they want to put my son in jail!”

Yuriy’s parents are intelligent elderly people who are close to 80. His mother Iryna has Alzheimer’s. Hennadiy gently strokes his wife’s hand:

“She doesn’t understand anything, recognizes no one; she’s like a child… I’m with her all the time, can’t leave her alone for a second. But, perhaps it’s better that way. She doesn’t understand what’s happening with Yura and our family. Otherwise, her heart would’ve snapped some time ago.”

Yuriy used to be a teacher of foreign languages in Sevastopol. He knows Ukrainian, Russian, English, Polish, Bulgarian, and is learning French, German, Spanish, and Italian. He was arrested and sentenced for publishing articles on his blog and appearing on television calling on Crimeans to fight Russian occupation, and for refusing to take Russian citizenship.

“Yuriy has always been a patriot, but he didn’t hate Russia. I myself am Russian, but Yura’s mother is a Ukrainian from Yalta, Ilchenko is her maiden name. Yura took it when he turned 18 because he wanted to have a Ukrainian name.”

PRISONER

Yuriy Ilchenko was imprisoned for eleven months. During this time he lost 30 kg. At first, they tried accused him of leading Pravy Sektor.

“The FSB told me to sign a confession that I coordinated Pravy Sektor activities in Sevastopol or in Crimea even though I’m not a member of that organization, or any other political party.”

He was thrown into a cell with common criminals – murderers, rapists, etc. The FSB beat Yuriy, told him to take Russian citizenship, humiliated him for speaking Ukrainian, didn’t allow him to read books and threatened to rape him.

The cells were overcrowded and damp; there were few beds so most of the men had to sleep on the floor. In addition, the light burnt constantly and the TV was always on. When Yura refused to wear the St. George ribbon on May 9, the officers didn’t allow him to sleep for several days.

There was no medical assistance. The men would find themselves in the same compartment as inmates with tuberculosis or they would be placed in solitary with other men suffering from AIDS.

Perhaps the worst conditions were in the punishment cell. It was a tiny underground room filled with rats and insects where people suffered from psora (a contagious infestation of the skin caused by the itch mite-Ed.). No medical care was provided.

Yura was allowed to read only during psychiatric sessions. He managed to read a collection of Crimean Tatar fairy tales and Quo Vadis? by Henryk Sienkiewicz (in the original). Another pastime in captivity was writing patriotic poems.

Why am I dying in a cage like a dog?

I did not steal and neither did I kill.

I loved my country, my native land,

A werewolf did I not want to become.

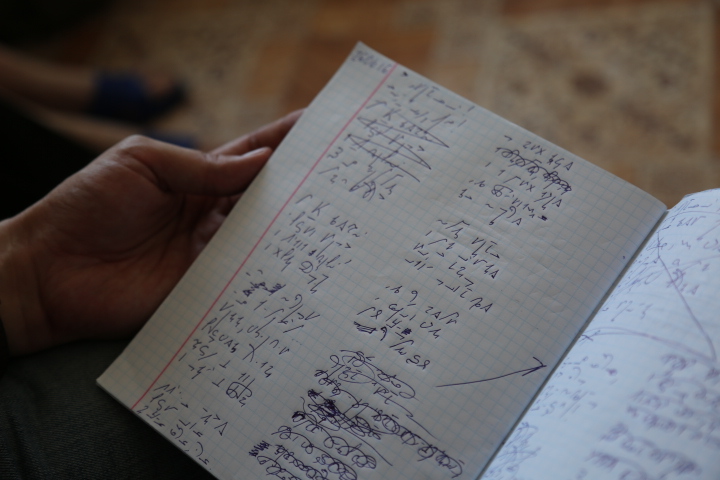

Yuriy wrote his poems in a coded language.

“I invented it in college. We had to take down lectures, and some professors spoke very quickly. I came up with a system where one symbol referred to a combination of letters or even a phrase. This really helped me in prison.”

In eleven months of captivity, Yuriy was allowed to see his parents only once. His father remembers:

“We went to see him once, but you can’t say we could really see him. The double glass panel was so dirty we could hardly make out his face, heavy grating separated us, and we had to talk through an old telephone.”

Yura was threatened with long-term imprisonment because the Russians accused him of “extremism” and “inciting ethnic and national hatred”.

A miracle happened on June 2, 2016: at the request of his lawyer, Yuriy was placed under house arrest. His father explains:

“They understood that if they sentenced Yuriy to long-term imprisonment, we, the parents, would be gone in 10 to 20 years. I think the judge just made it possible for him to spend some time with us.”

FREE AT LAST!

Yuriy was not allowed to leave the apartment, use the phone and the Internet, or communicate with anyone except his parents. The FSB also attached an electronic bracelet to his leg.

Knowing that he might be thrown behind bars for another ten years, Yuriy decided he had nothing to lose…

On the night of June 12, he cut the bracelet with a kitchen knife and left the apartment dressed in his father’s jacket and mother’s cane in his hand. He hitchhiked to the border.

The border was “secured” by what looked like an impenetrable wall of thick bushes and trees. Yura had heard that there were mines and booby traps on both sides of the border, but he knew it was better to die than spend his life in a Russian prison.

“My father didn’t want to let me go as he knew I’d get a life sentence if I was caught… or I’d be killed at the border.”

Yuriy decided to make his way through the thick green wall. He ran into barbed wire, and at one point almost fell into a deep hole. He crossed the border at night, in complete darkness, and in the morning he was in the free territory of Ukraine. His father recalls:

“The day after he left, Yuriy called me and cried exuberantly over the phone: “Dad, I’m free! I’m in Ukraine!”

Hennadiy smiles tearfully and tells us how worried he was for his son; the situation was hopeless – Yuriy had even tried to commit suicide when he was under house arrest. But, then he had this idea to escape… and he was lucky.

Yuriy wanted to get to Lviv, but only had enough money for a ticket to Mykolayiv. There he managed to renew his bank card where he still had some funds. The next day, Yuriy got on the train to Lviv, a city that he had always wanted to live in. Just as Yuriy’s train was pulling into Lviv, the police broke into his parent’s home in Crimea:

“They started throwing questions at us. They’d been searching for him all day. When they left, we began preparing for our departure… we sold some things, but they came again and warned us that they wouldn’t let us leave. But, you know the rest… another miracle happened!”

Yuriy has now found a new home where he and his parents will start a new life. He has rented a room and started giving English lessons.

“Actually, I could’ve fled abroad. I have a five-year US visa. I’ve been to 18 countries. I can still pack my things and go to Europe or the United States, but I will never leave my country, especially now, in these difficult times!”