Many in Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia see the association agreements they have now signed with the European Union as a step toward eventual EU membership, but an association agreement does not necessarily lead to that, as Türkiye which signed one in 1960 and other former European colonies which have, can attest.

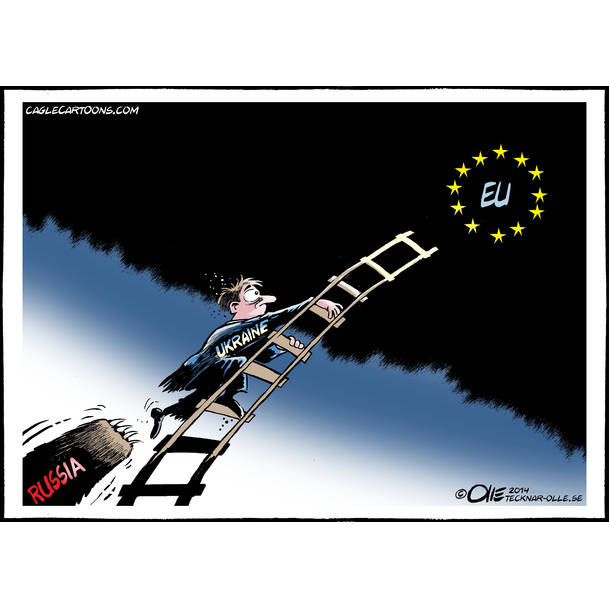

And that in turn means, Ruslan Gorevoy argues in an essay on Versia.ru that the three countries may have managed to distance themselves from Russia with all the costs that may entail without really joining Europe with all the benefits their governments and people hope for.

Even more important, although the “Versiya” commentator doesn’t say so, is that this intermediate and undefined situation will allow Moscow enormous room for maneuver in these three capitals, especially if Western leaders go out of their way to say that they have no plans for the further integration of these countries into the EU, let alone NATO.

The association agreements the three former Soviet republics have signed, Gorevoy points out, run for ten years, “and before the end of that time, even associate membership in the EU for those countries which have signed the document is impossible.” Moreover, the reality for them is “even darker.”

After more than a half-century has passed since it signed an association agreement with Brussels, Türkiye has not become “closer” to membership. It has, like other associates, gained access to certain markets and to certain financial and technical assistance. But that is all the pluses, the “Versiya” commentator says.

On the minus side, at least from the point of view of the citizens of associate countries, they have lost by signing part of their sovereignty because they have taken upon themselves the obligation to follow the dictates of Brussels concerning political, economic, trade and judicial reforms.

The majority of the 17 countries which have association agreements with the EU are former colonies of European states or portions of the former Yugoslavia. Besides those Yugoslavian successor states, “there was not a single European country in the list of signatory countries until recently.”

Few if any of those countries is going to be invited to become a full member of the EU, and Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia are unlikely to be. But they and their populations are going to be hit by the economic and political consequences of association, and that may spell trouble for those who signed on.

That is because, the commentator continues, “the people will give politicians one and the same question: why have we begun to live worse? And sooner or later,” the latter will have to answer with more than just slogans like “Europe is our choice!” or “We are Europeans!” And that situation may emerge “very quickly.”

Ukraine, for example, is going to cut its agricultural subsidies and a large share of its agricultural exports as a result. The same thing will hit Moldovan and Georgian wine producers. But they will all be hit hard if as seems likely Moscow restricts the number of gastarbeiters from these countries working and earning in the Russian Federation. Those who return home won’t be going to Europe.

Moreover, Ukraine may face a special problem with gas prices. Under EU rules, a country cannot sell gas abroad for more than it sells it at home. That means, at least potentially, that Kyiv will have to raise prices for Ukrainian consumers, something that is unlikely to make them happy.

And officials in all three capitals are likely to be less than pleased that many of their policies will now be reviewed by the EU Council of Association, “which consists of 28 representatives of the EU countries and one each from Kyiv, Chisinau and Tbilisi.” Especially irksome, Gorevoy says, is likely to be the fact that the council’s decisions can’t be appealed.

But the “Versiya” commentator concludes that it is really too early to talk about this. For the new association agreements to go into effect, “all member countries of the EU and the European Parliament must ratify them.” As of now, only one EU member has done so – Romania.

Source: Window on Eurasia